These days, the first couple of weeks of January have become a traditional period of abstinence and broken resolutions: As the Christmas decorations are packed away, our bodies mysteriously refuse to be squeezed into clothes that fitted just fine a few weeks ago.

Our ancestors had a better way of dealing with the end of the festive period: Hansel (or Handsel) Monday, also known as Diluain Traoighte in Gaelic. Traditionally, Hansel Monday is the first Monday in January and is marked by giving small gifts, tips or tokens (known as handsels) to servants, children and beggars, or to someone you owe a debt of gratitude. If you are given silver on Hansel Monday you are guaranteed good luck with money for the rest of the year. However, you should never give someone a sharp object as this will cut apart your friendship.

Apparently, luck could also be given in liquid form. In the Statistical Account of 1792, the Minister of Tillicoultry Parish tells the tale of William Hunter, a bed bound farm labourer cured of rheumatism “by drinking freely of new ale” on Hansel Monday. Not a story for anyone already struggling with their Dryathlon this January.

A confusing date

You might think deciding which day was the first Monday in January would be easy, but in some places, Hansel Monday was celebrated on the first Monday after 11 January. This was a result of the switch from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar system. This took place in Scotland in September 1752 and resulted in the “loss” or as some saw it “theft” of 11 days – people went to bed on the evening of 2 September and woke up the next morning on 14 September. This perceived theft of 11 days seems to have been deeply resented in some parts of Scotland, and as a result the date of Hansel Monday was often calculated as the first Monday after 11 January.

Rowdy neighbours

Some places were more enthusiastic than others in their celebrations of Hansel Monday. The inhabitants of Crieff in the 1800s seem to have been particularly rowdy, seeking drunken revenge on neighbours who had upset them by blocking chimneys and blowing penny whistles through keyholes in the middle of the night. In 1831, even the local instrumental band were noted for their drink-fuelled brawling.

The villagers of East Wemyss in Fife held a more civilised celebration that may have had its roots in the medieval period or earlier. On the night of Hansel Monday, they would make a torch-lit procession to the Well Cave, one of a group of caves in the sea cliffs around the village. Wine and cakes would be consumed, hymns would be sung and the older members of the village would go back home, leaving the youngsters to make their own entertainment.

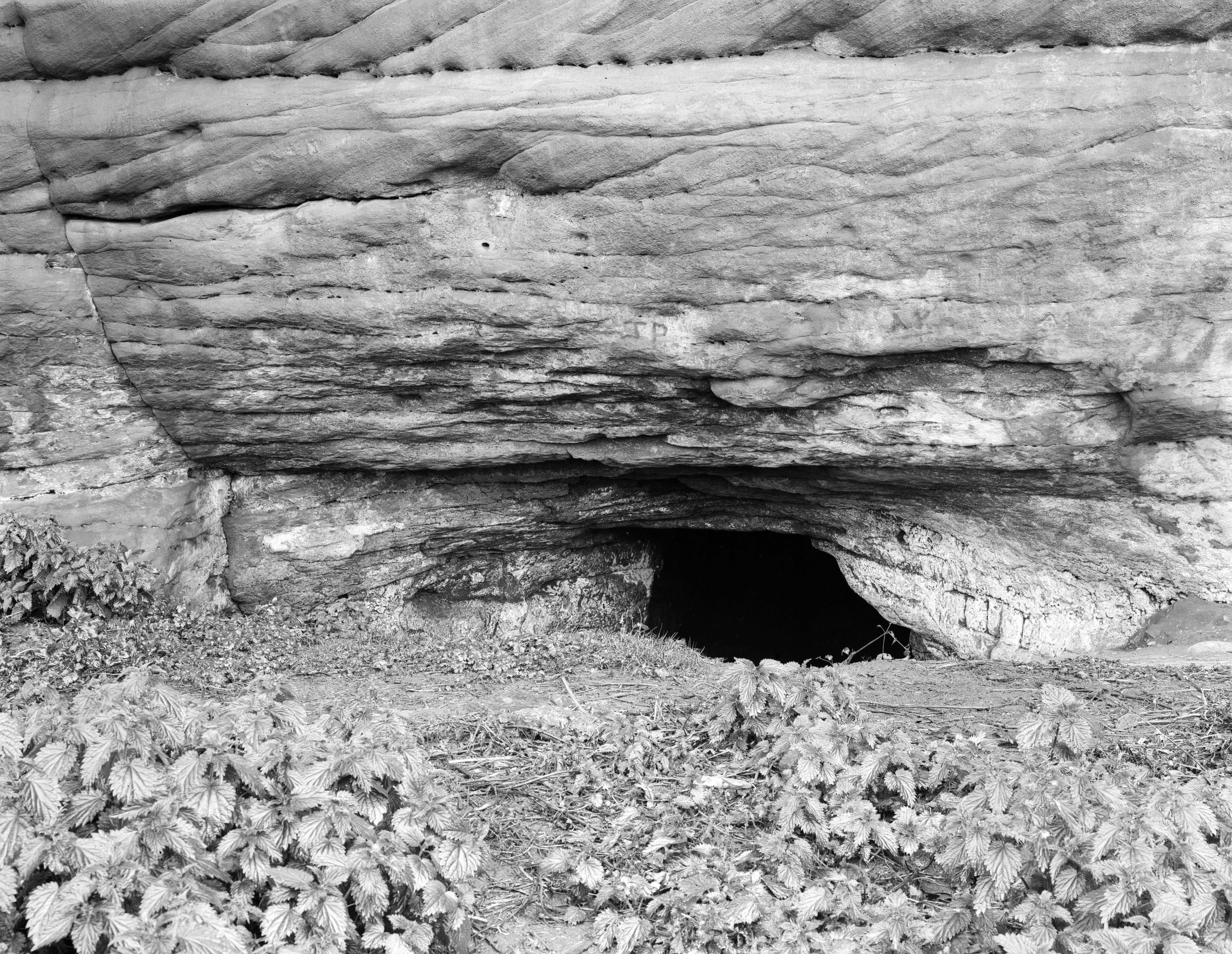

The mouth of Well Cave. © Crown Copyright

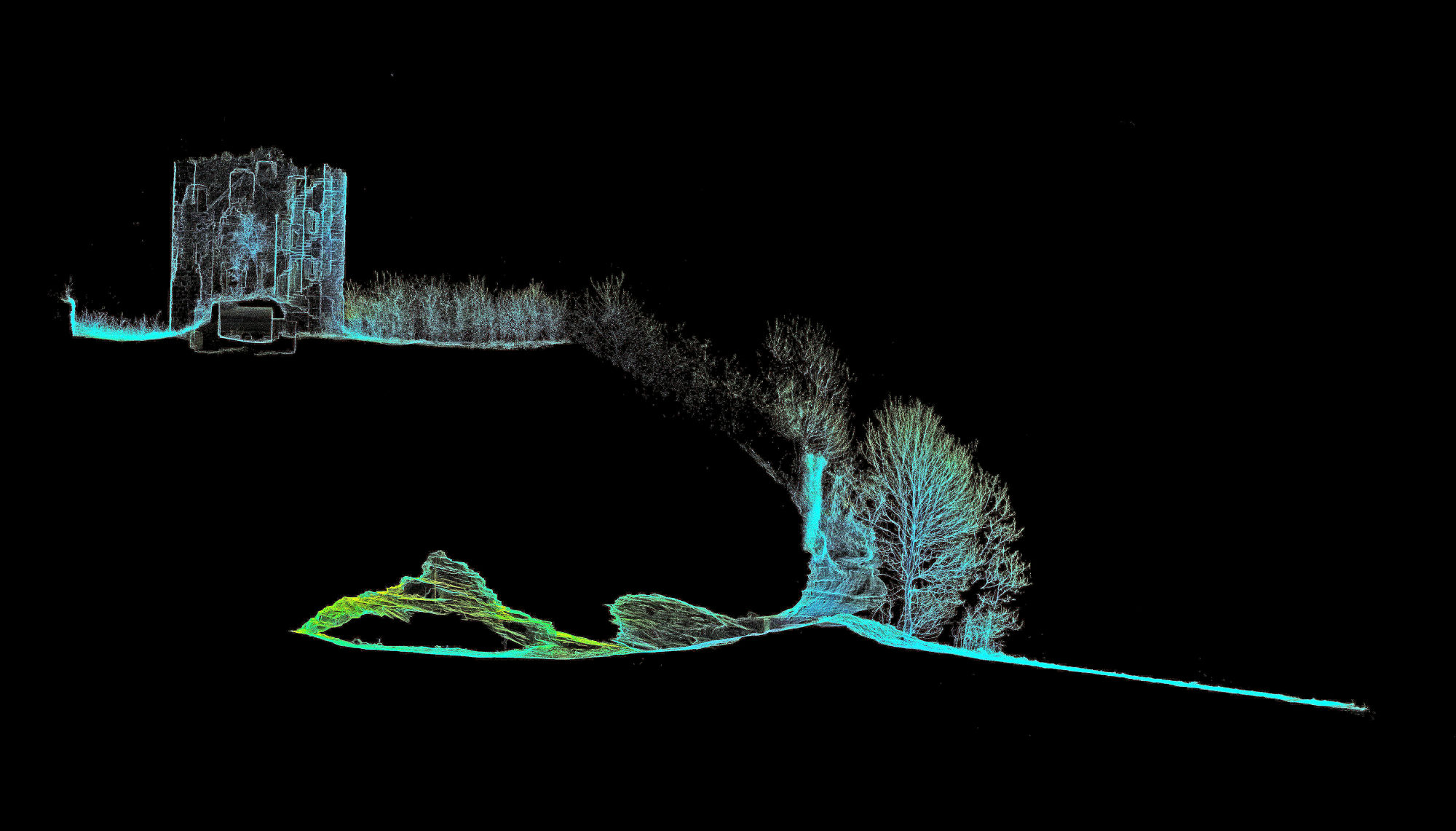

The risk of rock falls means the Well Cave is no longer safe to enter, but a joint project by Historic Environment Scotland, the SCAPE Trust and the Save the Wemyss Ancient Caves Society (SWACS) is working towards scanning all of the caves along the shore at Wemyss and recording the important Pictish carvings on their walls.

A cross section of Well Cave with Macduffs Castle above. © SCAPE

Over time, Hansel Monday traditions have faded and been absorbed into other festivals; gifts at First Footing on Hogmany, and misbehaviour at Halloween. So this Hansel Monday, why not start your own tradition and make your own luck. If you get the chance, you could walk the mean streets of Crieff, or if the tide and weather are right, visit the coastal path that runs along the shore at East Wemyss. Historic Environment Scotland cannot, however, recommend aggravating your neighbours in the middle of the night or attempting to cure existing medical conditions through excessive alcohol consumption.