Perth Museum was previously known as Perth City Hall and its future had been of constant concern long before I joined the organisation in 1993.

It had functioned pretty much as any town hall in the first 100 years of life, being the venue for many public events from school concerts and ceilidhs to political conferences and rallies. Some famous names performed on its stage including the Kinks, The Who, Lulu and Morrissey. Following this heyday, however, its role became uncertain.

A symbol of prosperity

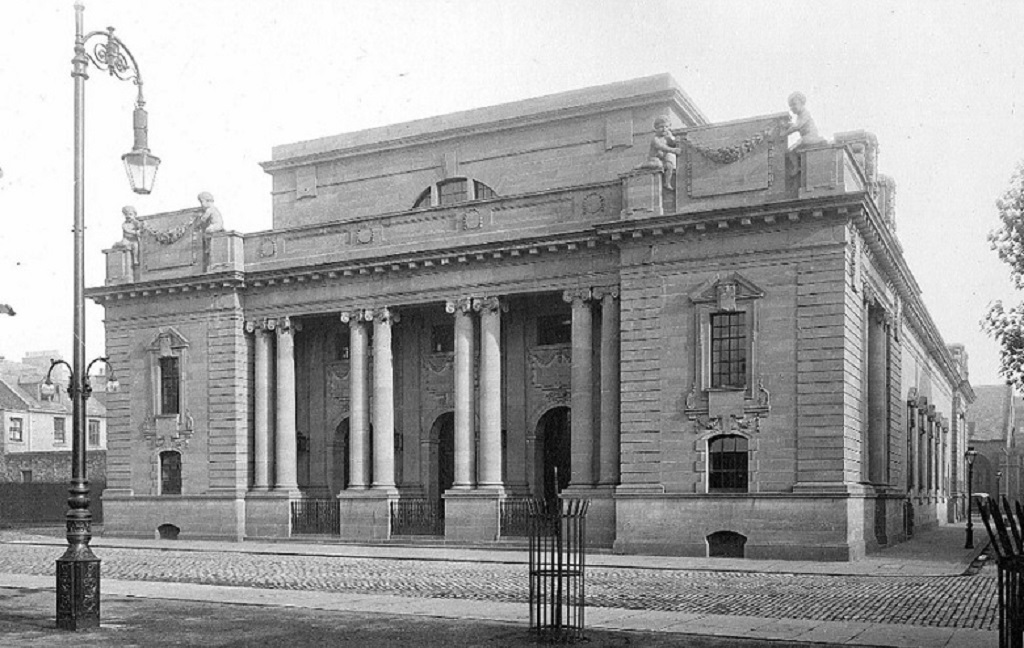

The current building replaced an earlier town chambers which had started to collapse by the end of the 19th century. The city decided to hold a design competition in 1907, judged by Sir John James Burnet, Scotland’s pre-eminent architect at the time. The winners were Glasgow architects Henry Clifford and Thomas Lunan. They proposed a formal classical design in the Beaux-Arts style.

Perth City Hall around 1914 (© Perth Museum)

In the later part of the 19th century, the splendid civic halls of industrial towns like Manchester, Bolton and Paisley would have been fresh in the minds of any self-respecting mill town wishing to showcase its industrial prosperity.

Although the architecture of the new Perth City Hall was monumental in its design language, it is representative of a time when civic architecture was becoming more friendly in scale and feel. Cardiff Town Hall (1906) makes for a close comparison. It seems likely the unusual design of the rear windows at Perth are directly influenced.

Clifford and Lunan’s building was modern in the way it was designed ‘in the round’ and used concrete for construction. However, the classical external detailing and Baroque interior relied on the movement of Historicism to please the civic aspirations of the time.

Cardiff City Hall may well have influenced the design of Perth City Hall (Yummifruitbat, via Wikimedia Commons)

On the map

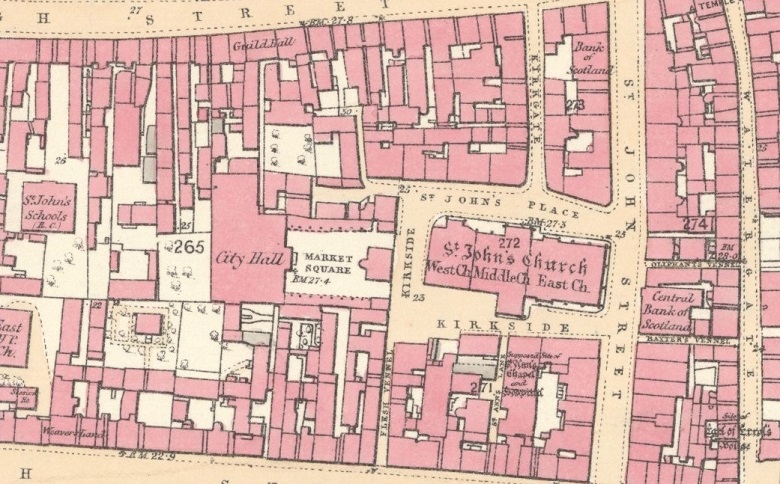

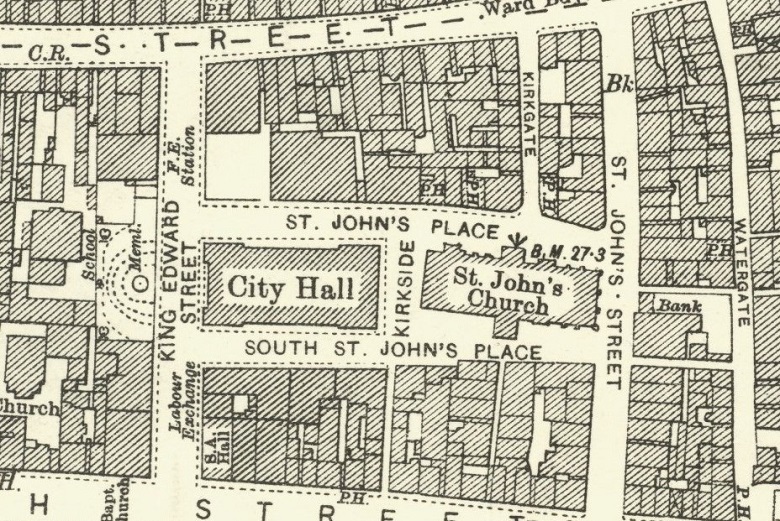

The new City Hall had a simple plan. There was to be an entrance hall at the west end, a main hall and a lesser hall behind it to the east.

The site chosen for the new building was located centrally between the High Street and South Street, immediately to the west of St John’s Kirk. At that time the ground was occupied by a flesh and butter market and the previous City Hall.

The new building occupied the entire site. New streets had to be created around it, along with a new square to its west front. The Ordnance Survey maps below, from 1860 and 1931, clearly show the difference it made to the Perth streetscape.

The Ordnance Survey showing the site of Perth City Hall in 1860. (Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland).

The Ordnance Survey showing the site of Perth City Hall in 1860. (Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland).

Demolition?

Perth City Hall was listed at category B in 1977. But by the 1990s, it was clear that it didn’t provide the facilities required by modern concert and conference venues. It finally closed at the opening of the new Perth Concert Hall in 2005.

The City Hall lay vacant for a number of years while the Council considered alternative uses. The lack of an obvious use, and divided opinions on the attractiveness of the building, resulted in ongoing discussions about the merits of keeping it. In 2011, an application was lodged by Perth & Kinross Council to demolish the building and create a public square.

Our predecessors (Historic Scotland) acted on behalf of Scottish Ministers in determining such listed building applications. The application was refused because it was unclear whether all options for the re-use of the building had been explored. It was recommended that the building be sold to someone able to restore it.

After carrying out a marketing exercise, the Council submitted another demolition application in 2014. However, two schemes had been submitted for the building’s re-use as a public market and a hotel. There was also growing interest from members of the public in retaining Perth City Hall. The Council received nearly 2000 letters objecting to its demolition. Viable proposals were now in place that would secure the future of the building. The Council decided to withdraw the application and consider their position.

The Main Hall in 2018. The arched recess originally contained an organ that had been removed in about 2006. (© Mecanoo).

A new lease of life

At this time, funding for regional cultural and tourism projects became available from the Tay Cities Region Deal. It was decided that the City Hall would become the principal focus of the Perth Cultural Transformation Project. A £27m scheme would see it redeveloped into a museum. One which could potentially provide a new home for the Stone of Destiny.

The Council proposed an international architectural competition for the building’s revival but had reservations about it being adapted to a new use because of its listed status. Our team knew this would be achievable and I offered to write the design section of the competition brief. While the Council focused on the functional requirements of the building, I provided them with a statement of significance and a design narrative. This guided entrants on the key characteristics that should be preserved and areas where greater intervention might be possible.

Eventually, five architectural practices (three from Scotland and two from the Netherlands) were shortlisted and invited to submit schemes. A public consultation was held in the summer of 2018, inviting comments on the five schemes. To avoid a conflict with our statutory role in advising on any listed building consent that might come forward, my consultation comments were limited to the relative impacts of the proposals on the cultural significance of the building.

A competition image showing one of the proposed new entrances to Perth City Hall. (© Mecanoo)

Visons of vennels

Taking these views and a number of other factors into account, the Council selected Netherlands firm Mecanoo as the winner. Mecanoo impressed with their enthusiasm for the listed building’s qualities and their intention to be as ‘light touch’ as possible in its transformation.

The practice was very taken by the historic vennels of Perth and re-oriented the building with a new vennel-like entrance space near its east end. This kept the main circulation space and new entrances together while separating the café from the exhibition space in the main hall. Their design left the large volume and its architectural features largely untouched, while transforming it into a modern exhibition space through a series of reversible interventions.

Inside the museum’s Main Hall. A free-standing exhibition space stands in the middle of the hall. The seating has been replaced by a new gallery at about the same level. The original doorways and staircases remain in use. (© HES)

The Council said it was very grateful for our help in finding an imaginative scheme for the City Hall’s re-use, which could also achieve a consent and was financially deliverable.

My colleagues from our designations team visited recently and were very impressed by the conversion of the building. They see it as an exemplar of its type in the light-touch approach taken by the designers, who have managed to achieve an ambitious transformation in a way that doesn’t feel awkward or contrived.

Working at risk

I have worked with several buildings that have fallen out of use and are recognised as being ‘at risk’. The public interest in seeing the building retained was very heartening and contributed to the Council’s decision to keep it.

Holding a design competition was an interesting approach because we were working at risk. This can sometimes be necessary to unlock a future for buildings that have stagnated. Writing the design brief had an element of risk to it because it would not be possible to fully predict the quality of the resulting competition entries.

However, Historic Environment Scotland were able to bring our expertise to the competition by creating a clear framework the designers could use to preserve the best qualities of the old City Hall while creating an exciting new museum for Scotland.

Perth Museum today. The large glazed slots in the side walls featured in the competition proposal were subsequently replaced by statement doorways. (© HES)

Discover more

Perth Museum is open to the public 7 days a week.

If you’d like more stories and updates from our Heritage teams then be sure to sign up to Lintel, our Heritage newsletter. You can also register for our Friday blog alert to get the latest stories delivered straight to your inbox.