The recent spell of bad weather has seen far reaching consequences across the United Kingdom. Here in Scotland, December proved to be the wettest calendar month ever recorded by the Met Office, with a record breaking 215% of the expected average rainfall. Subsequent flooding experienced throughout the country has made the headlines.

With that in mind, it seems relevant to take a look at the changing rainfall patterns observed here in Scotland, in recent times and in the near future.

Forming a link between climate change and the supposed regularity of extreme rainfall events could command numerous articles in its own right, however, what we can address, and with a high degree of confidence, is that over the past 100 years or so annual rainfall levels in Scotland have been increasing.

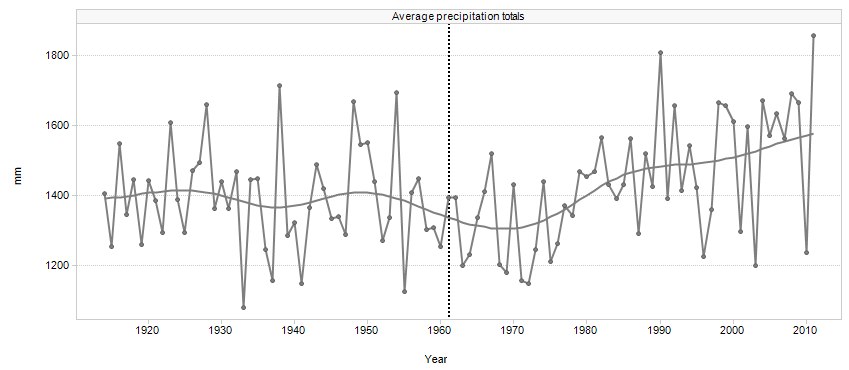

Data published by Sniffer, in Scotland’s Climate Trends Handbook, shows that since the early 20th Century, rainfall levels have increased in Scotland by around 11%. On a shorter timescale, since the early 1960s, annual rainfall levels have increased by around 27%. Importantly, the same source of information shows us that we now experience more days of heavy rainfall (>10mm in a 24 hour period), with an increase in these events of 8.2 days per year, again since the early 1960s.

In summary – it is wetter now than it has been in the recent past (Scotland’s Climate Trends Handbook, Sniffer 2014).

Total precipitation for Scotland, 1914 to 2011. Smoothed line displaying running averages. Vertical dashed line marks 1961 (Source: Scotland’s Climate Trends Handbook, Sniffer 2014).

Constraining future conditions is a trickier task to carry out, due in part to the unpredictable nature of our climate system.

However, future climate modelling work carried out by UKCP09 suggests that by the 2050s, Scotland can expect to see annual rainfall levels decrease marginally by about 1%.

Hidden within this overall decrease, and in stark contrast, winter rainfall levels specifically are predicted to increase, in some cases by as much as 16%. It should be noted here that the reality of these figures will depend on the measures taken to reduce global emissions, so in fact we could experience a higher or lower change in annual figures.

Generally though it is widely accepted that we will have drier summers but much wetter winters.

How will altering rainfall levels affect the Historic Environment?

Water is a critical component in several types of deterioration in the historic environment. It is directly involved in most chemical, physical and biological decay processes as well as indirectly in, for example, the dissolution and migration of salts, which play an important role in the decay of stone masonry specifically. Increased time of wetness and depth of penetration (as a result of increased rainfall) has exposed our stone built historic structures to a greater level and speed of deterioration, with this trend anticipated to continue into the future.

It is important to note that many older structures are, by their very existence (and survival), resilient objects, that can cope with a certain degree of wetting and drying.

However, it is possible that the rate at which our climate is changing will outpace the ability of a structure to tolerate such processes, and where this happens we will see the negative impacts of climate change on our built environment.

At many sites we have introduced adaptation measures to counteract the impacts of increased rainfall; for example, we have ‘soft-capped’ exposed wall heads at a number of vulnerable sites, including at Bothwell Castle and Castle Sween. This forms a natural and ‘green’ protective barrier that is seen to be technically effective, as well as visually acceptable. Further information on this technique is available here, in one of our many technical publications.

An example of soft-capping, installed at Jedburgh Abbey, which acts to reduce the amount of water seeping into exposed wallheads

Further Information:

(1) Scotland’s Climate Trends Handbook: A fantastic source of national and regional climate trends.

(2) Adaptation Scotland’s Climate Ready Places: A new, interactive resource encouraging people to think about what a climate ready Scotland would look like.