During the First and Second World Wars, the River Clyde was an important port and shipbuilding centre – which meant it had to be protected from attack. We set out to uncover how this was done.

The HMS Hood, the largest warship in the world at the time of its launch in 1918

The munitions industry and the building and maintenance of warships were vital to the war effort. The Clyde was also a major transport and economic centre on the west coast of Britain, alongside Liverpool and Manchester.

As it was so important to the war effort, a series of coastal defences were built to protect the Clyde estuary from attack.

If you’d visited one of these coastal battery sites, you would find:

- large guns capable of tackling enemy warships

- searchlights

- observation posts

- crew accommodation

The First World War sites were located at Ardhallow, Cloch Point, Portkil and Fort Matilda. A new site at Toward was built during the Second World War and the batteries at Ardhallow and Cloch were modified and reused.

Map of the coastal defences

Recording the surviving defences

So, how did we start to find out more? Initially, we did some desk based research. This involved studying Fort Record Books held at the National Archives in London.

We then set off out into the field to identify and record the surviving remains.

We weren’t surprised to find that a number of the structures had collapsed, been removed, or the sites redeveloped. After all, these defences were often built in a hurry out of bricks and shuttered concrete. At Fort Matilda for instance, all that survives are two war department boundary stones marking the limits of the site. Fortunately though, we found much more surviving at the other sites.

Portkil battery was the best preserved of the First World War sites. Many of the buildings still stand, including gun emplacements and magazine stores. There are also two fantastically well preserved wooden cartridge lifts. These would have carried ammunition from the underground magazine stores to the guns above.

View of the catridge lift and hatch

We recorded the surviving remains by taking photographs, mapping the location of each feature and writing descriptions. For important or unusual buildings and features, we also created measured drawings.

You Ain’t Seen Me

The sites at Cloch and Ardhallow were designed to be well hidden by trees and artificial camouflage. To this day at Ardhallow, parts of the site remain concealed by trees and dense vegetation.

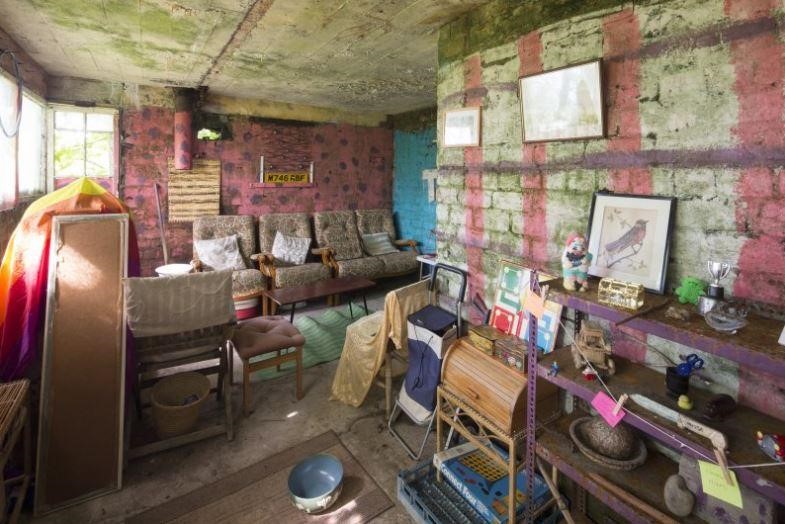

Meanwhile its Battery Observation Post has undergone a different sort of camouflage, as it’s now a rather impressive kids clubhouse!

The interior of battery observation post at Ardhallow, now a clubhouse. The rangefinder plinth is concealed by a rainbow flag.

The guns installed at these sites were impressively powerful. Ardhallow was initially armed with a 9.2-inch gun and two 6-inch guns! However, the 9.2 inch was withdrawn from service in 1906, after test firing proved powerful enough to blow out the windows of the houses to south of the battery…

Remains of the Day

Much of Cloch Battery now lies beneath a caravan site, but the command post buildings survive. We also saw two searchlight emplacements, used to illuminate targets at night.

Another surviving feature we recorded was a small metal post on the shore by Cloch lighthouse. It doesn’t look like much, but it served a vital function as an anchor point onto which an anti-submarine boom was tethered.

The boom was made up of two parallel subsurface metal nets with surface floats. It stretched across to another anchor point at Dunoon to prevent enemy submarines and ships sailing up the Clyde estuary.

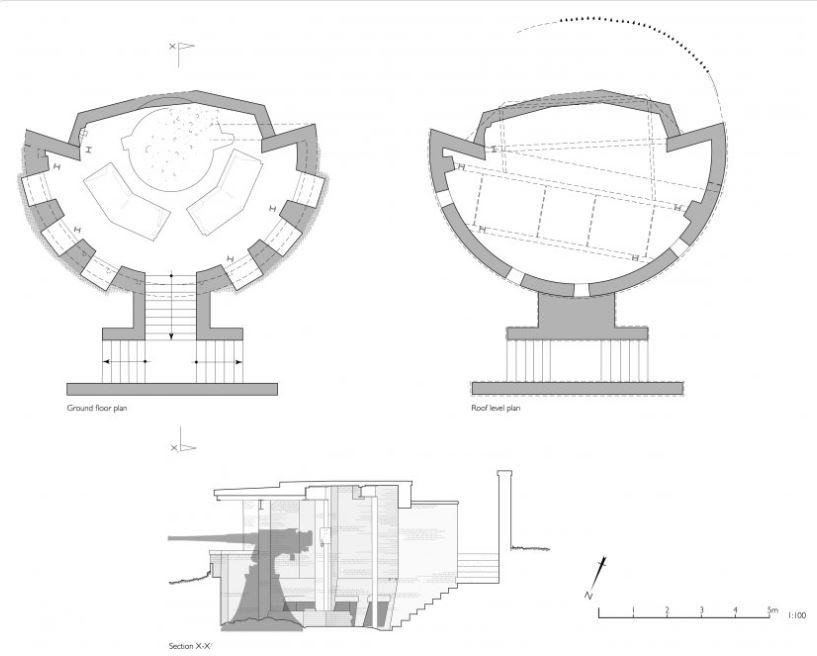

Detailed plan and sectional elevation of one of the Second World War gun emplacements at Toward Point

We were joined at Toward Point by students from the Centre of Battlefield Archaeology at Glasgow University. They helped us photograph and map the site. It is particularly well preserved. The majority of the brick buildings are still standing and evidence of the wooden buildings, such as accommodation huts, are visible as earthwork platforms.

These huts would have housed the soldiers who worked in shifts to man the guns and observation posts 24 hours a day. Women also served at Toward and we recorded the remains of two huts for the ATS (Auxiliary Territorial Service), which was the women’s branch of the British Army.

Defending the Defences

Each site also had a network of defences around them. These included blockhouses (pillboxes), trenches and barbed wire to prevent attack from land.

We also discovered the faint traces of trenches zig-zagging the fairways of Greenock Golf course. These were part of the Lyle Hill position which defended Fort Matilda. At Toward, we recorded a network of machine gun posts. These survive as grass-grown mounds. At Ardhallow, we discovered a series of well preserved trenches.

Recording a trench at Ardhallow

Our project has produced hundreds of new site descriptions, photographs, survey drawings and maps.

You can explore our findings further by searching the National Record of the Historic Environment – aka Canmore.