Today is World Smell Day, where we’re encouraged to spend a bit of time following our noses and appreciating our sense of smell. Fancy joining us as we explore some of our sites with our nostrils instead of our eyes? We’ve asked some of the experts at Historic Environment Scotland to reveal the whiffiest locations in Scotland’s history.

Brace yourself and take a deep breath as we reveal some of Scotland’s smelly past!

The malodourous monks of Melrose

Sally Gall, Interpretation Officer, imagines the odours blowing on the breeze at Melrose Abbey – Scotland’s first Cistercian monastery, founded in 1136.

Melrose Abbey would not have been so fragrant in medieval times.

A walk through a medieval town or abbey would have been a varied journey for the nostrils, with smells both sweet and sour from building after building. At Melrose, the most important building was the church. It would have been filled with heady smelling incense, smouldering on altars.

There would also be the aroma from the kitchens. The monks would have been served in the refectory. The Rule of St Benedict guided their eating habits: ‘Two kinds of cooked food, therefore, should suffice for all the brothers, and if fruit or fresh vegetables are available, a third dish may also be added. A generous pound of bread is enough for a day whether for only one meal or for both dinner and supper.’

There’s a record of the monks at Melrose having grape vines – presumably tended in some sheltered corner. The vineyard itself would have had a pleasant, subtle scent as the grapes grew and ripened. During the wine-making process, the fermenting grapes would smell first like rotten fruit, gradually sweetening to richness.

Then things get a bit niffy. You might’ve wanted to hold your nose passing the ‘great drain’, which took the effluence away from the abbey latrines. We also know that the monks used pisspots, which must have been pretty smelly.

The latrine block would have run under the monks’ dormitory along the east range of Melrose Abbey.

These ceramic urinals were found during excavations at Melrose Abbey

Near the abbey, wool would have been sorted in sheds. The wool would be cleaned and graded after being brought in from the abbey’s sheep farms. There would probably have been a strong smell of lanoline (sheepy!).

Later in its history there was also leather tanning on site. Tanneries were notoriously stinky spots. Hides would arrive covered in muck, hair and rotting flesh. The hides would be scraped down, then soaked in urine to remove the hair. The leather was then softened by pounding dung into the skin. Any volunteers for having a go? Not me!

The tanning pits at Melrose Abbey are a reminder that monastic life was not simply one of prayer.

Overall, Melrose must have stank. And other medieval settlements probably weren’t that different!

Nosing the whisky at Dallas Dhu

Alasdair Joyce, steward at Dallas Dhu Historic Distillery describes the reek of the whisky-making process which assailed the neighbours when the distillery was operational.

Living next to a working distillery can be a bit smelly for the neighbours!

Silent though it is now, the ghosts and spirits of what – and who – have passed through the doors of Dallas Dhu in the last 120 still capture the imagination of the visitors. However, when I first encountered the distillery in 1981 it was still a going concern. What wafted around and through it was much more organic in nature, and at times, quite powerful.

There is always a smell from a working distillery, but this changes according to the process currently under way, be it mashing, brewing, or distilling. Malting carries its own distinctive perfume as well.

Mashing produces a wonderful smell of warm malt, comforting and appetising. Brewing starts off as aromatic and beery but can, and often does, degenerate into something more pungent and yeasty, and somewhat overpowering.

These are the washbacks at Dallas Dhu. Sugary wort would be poured into these huge containers. Yeast would be added and fermentation would begin.

Distilling allows some of the finest, and not so fine, aromas to lift into the air and give a hint of either what is to come after the whisky has matured, or a less subtle hint of what has (fortunately) been allowed to escape from the new spirit in the form of acrid and sometimes downright foul sulphurous fumes. There are, after all, some things that the angels would not want to share!

Woe betide the unwary householder who put laundry to dry outside at such a time. It would absorb its fair share of this airborne cocktail, but silently, sneakily, only to release it by degrees sometime later when a warm steam iron was passed over it. We were left wondering whether the fault lay with the washing machine or the laundry powder, before realising that the problem lay much further outside our control!

I wish I had paid more attention to what went on inside the distillery in those days. I remember the people, the faces, and some of the names. I should have taken photographs and remembered more. But then, memories are not bits of paper, they are what we hold inside us, and perhaps we do better to hold onto them in that way. And maybe the malodorous cocktail that assailed me some winter mornings is best forgotten!

The bouquet of the Bearsden bath-house

Interpretation Manager, Steve Farrar, muses on the smells that might have made their way up your nostrils in a Roman outpost.

The bath-house at Bearsden would have been the hub of the fort. Soldiers would have socialised and relaxed here.

The Roman fort which once stood at Bearsden is now mostly covered by roads and houses, but remains of the bath-house within its annexe can still be seen.

A visit to this suburban site gives visitors a remarkable insight into the daily lives of the soldiers stationed along the Antonine Wall.

The Bearsden bath-house was divided into seven sections, including hot and cold baths. Imagine the savoury (or, possibly, unsavoury) smells as a troop Roman soldiers sweated it out in the steam room. They wouldn’t have used soap to get clean. Instead, they probably rubbed olive oil onto their skin and then scraped away the oil, sweat and dirt with a special tool. Perhaps they finished the job with some nicely scented oils.

Next door to the bath-house was the latrine block that served the fort’s soldiers. This was not so fragrant.

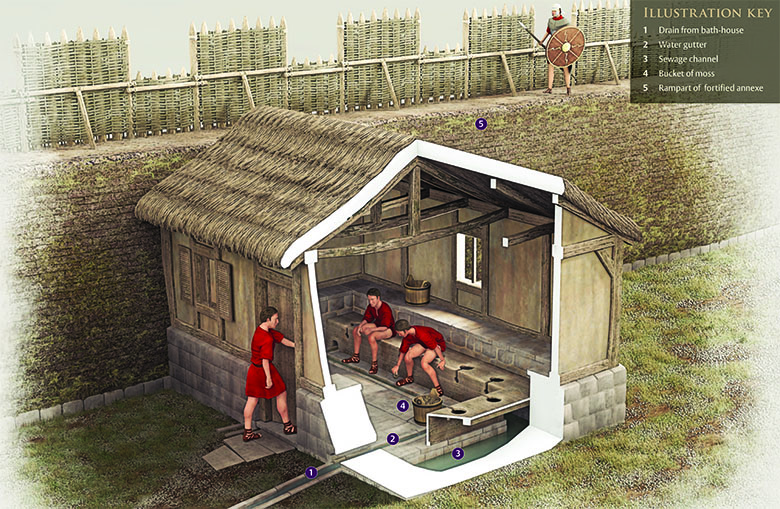

Going to the loo in Roman times was a communal experience.

The communal toilets were shared by up to 100 men and offered no privacy. The same basic design was used in military facilities across the Roman Empire. Seats were suspended above a sewage channel flushed by drains from the bath-house.

Instead of toilet paper, the soldiers probably used moss dipped into water that flowed along the open gutter at their feet.

Evidence of what the soldiers ate emerged from a nearby defensive ditch, which had filled with human sewage from the latrine. Microscopic analysis revealed a mostly vegetarian diet with imported Continental luxuries like figs and coriander.