As part of Heritage Awareness Day 2018, Historic Environment Scotland celebrated Scotland’s historic links with the rest of Europe.

Many Europeans have achieved fame and fortune in Scotland whilst many Scots have been on incredible adventures in Europe. Read on for a glimpse of some of their exploits.

The fearsome warrior who hurled Robert the Bruce’s Heart into the middle of a battle in Spain

The last thing an unassuming visitor to the small Andalusian mountain town of Teba might expect to find in the central square is a large slab of Dumfriesshire marble.

![By Keltyber [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons A stone monument in surrounded by a low chain fence. There is an inscription in black and gold writing on the front of the monument. Buildings typical of southern Spain are in the background.](http://blog.historicenvironment.scot/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Douglas-Monument-in-Teba-attrib-By-Keltyber-Public-domain-from-Wikimedia-Commons-1024x768.jpg)

Keltyber / Public domain via Wiki Commons

It forms a monument commemorating the Battle of Teba, fought in August 1330 as part of a lengthy campaign King Alfonso was waging against the Moorish Emirate of Granada. Providing unusual backup to the Spanish forces was an errant of Scottish knights led by a fearsome fighter known as “Black Douglas.”

Sir James Douglas was a fiercely loyal subject to Robert the Bruce, who had died a year earlier. He fought alongside Bruce at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 and, upon the King’s death, had been entrusted with caring for his heart, which had been cut out and placed in a small silver casket.

![By Jose Castillero Guerrero [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons A general view of a Spanish mountain town. There is a ruined castle on a hill overlooking the town.](https://blog.historicenvironment.scot/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/View-of-Teba-attrib-By-Jose-Castillero-Guerrero-CC-BY-SA-3.0-httpscreativecommons.orglicensesby-sa3.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons-1024x576.jpg)

Jose Castillero Guerrero / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) via Wiki Commons

So what was “Black Douglas” doing in this remote part of southern Spain? The Battle of Teba gave him the ideal opportunity to carry out his king’s dying wish that his heart “be carried into battle against God’s foes.”

True to his word, Douglas entered the Battle of Teba wearing the casket. He is said to have thrown it into the melee with the words “go first as thou hast always done.” It was to be his last act of loyalty. He was killed in the fight and his body, along with the casket and Bruce’s heart, returned to Scotland.

The Scottish engineer who devised a secret plan to destabilise the French economy

William Playfair was born in 1759 in Liff, near Dundee. The son of a parish minister, he is an undervalued figure in Scottish history despite leading a live that would not be out of place in a Hollywood blockbuster.

Playfair, who was the uncle of the well-known architect William Henry Playfair, tried his hand at a variety of careers. As an engineer and political economist, he is credited with inventing three fundamental forms of statistical graph—the line chart, the bar chart, and the pie chart. At other stages in his career he worked as an inventor, banker, secret agent and journalist.

![By William Playfair [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons An early example of a line chart showing Imports and Exports in England.](https://blog.historicenvironment.scot/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Chart-by-William-Playfair-1786-attrib-By-William-Playfair-Public-domain-via-Wikimedia-Commons-1024x719.jpg)

A graph produced by William Playfair (William Playfair / Public domain, via Wiki Commons)

Many of Playfair’s most notable exploits took place in France. On 14 July 1789, he took part in the storming of the Bastille.

Then, between 1789 and 1791, he was involved in a bungled land selling scheme which attempted to establish a colony of French settlers on the Ohio River. The collapse of the scheme, which also included American Founding Father Thomas Jefferson, prompted Playfair to flee the Continent.

![Henry Singleton [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons An artist's impression of the Storming of the Bastille. Two women are in the centre of the picture surrounded by soldiers and a mob. Smoke rises in the background.](https://blog.historicenvironment.scot/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Storming-of-the-Bastille-by-Henry-Singleton-attrib-Henry-Singleton-Public-domain-via-Wikimedia-Commons-1024x739.jpg)

The Storming of the Bastille by Henry Singleton (Henry Singleton / Public domain, via Wiki Commons)

Playfair’s return to Britain was the beginning of his most notorious escapade.

In 1793, the revolutionary French government was becoming a cause of concern to Britain. Working closely with War Secretary Henry Dundas, Playfair devised a plan to destabilise the French economy. He suggested that he:

“fabricate one hundred millions of assignats and spread them in France by every means in my power.”

This, he argued, would attack the French government without the need to spill blood. With the go-ahead from Dundas, he set about counterfeiting the money in a castle in Northumberland. He then distributed it via a complex secret network in France. By 1795 the French currency was worthless.

Despite being responsible for one of the most audacious espionage operations in British history, Playfair died in obscurity in London 1823.

The Polish bride of a Jacobite king who was kidnapped on the way to her wedding… and the Irish adventurer who rescued her

Throughout history, many diplomatic marriages have been arranged between Scottish and European royal houses. Few were as dramatic as that between James Francis Edward Stewart and the Polish Princess Maria Clementina Sobieska.

Worried that he was reaching 30 without a bride or an heir, “the Old Pretender” tasked a loyal Irish adventurer named Charles Wogan to find him a suitor. Wogan travelled around the courts of Europe searching for an appropriate bride. Eventually he suggested Clementina. In October 1718, she set off for Bologna for the wedding.

The wedding plans were soon scuppered. As the Princess and her mother travelled through Austria, they were ambushed and arrested by troops belonging to the Holy Roman Emperor. The pair were detained in Innsbruck Castle. The arrest had been made at the request of King George I of Great Britain, who was keen to prevent a Stuart marriage.

Clementina was eventually freed by a group of rescuers – led by none other than Charles Wogan. She reportedly made her escape from the castle disguised as a maid.

After a treacherous winter journey over the Brenner Pass, Clementina finally reached Bologna in April 1719 – but no bridegroom was waiting for her. James had travelled to Spain to lead a Jacobite rising, leaving instructions for a proxy ceremony.

The pair finally met on 2 September at Montefiascone, Italy. Their official wedding took place on the same day in Cathedral of Santa Margherita. They settled in Rome where Clementina gave birth to a son. He is known to history as Bonnie Prince Charlie.

The Italian aeronaut who caused a frenzy in Edinburgh and Glasgow… and terrified farm workers in Fife

Vincenzo Lunardi (1754 – 1806) was an Italian aeronautic pioneer who travelled to Britain in 1785 to demonstrate his “Grand Air Balloon.” “The Daredevil Aeronaut” captured Scotland’s imagination. His visits to Edinburgh and Glasgow were major events.

Balloon-shaped head gear became a must-have accessory among fashionable Scottish ladies. In his poem ‘To a Louse’, Robert Burns wrote about a young woman who had a louse scampering in her Lunardi bonnet.

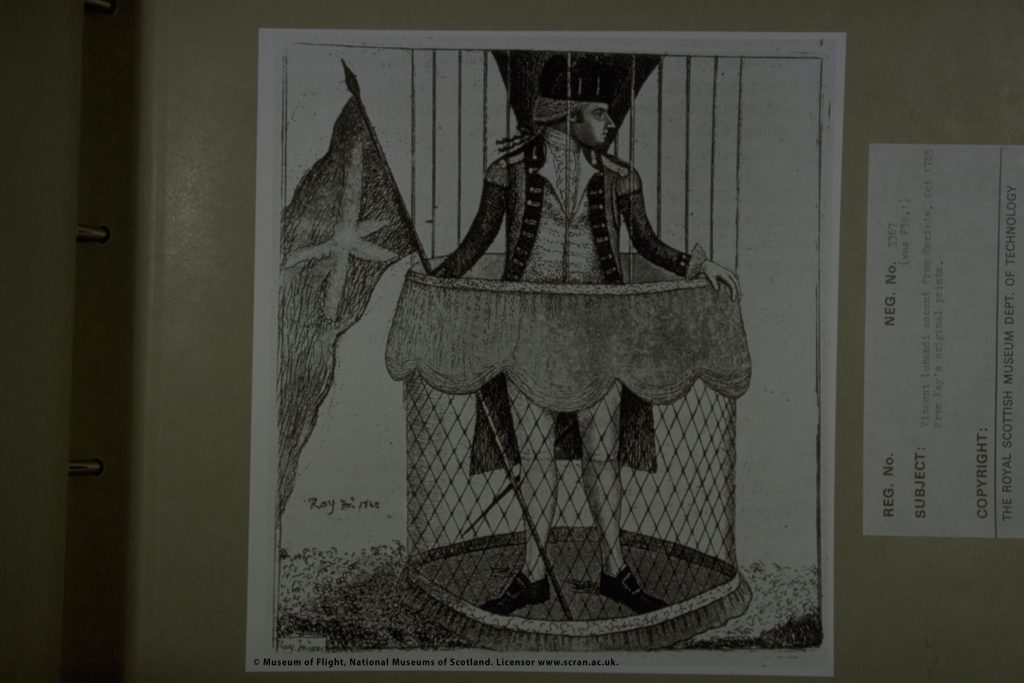

An archive image of Lunardi standing in the basket of his balloon prior to lift off from Heriot’s Hospital (courtesy of Scran)

Lunardi made a total of five flights in Scotland. His first take-off was in October 1785 from the packed grounds of George Heriot’s School. The Scots Magazine described the scene:

“The beauty and grandeur of the spectacle could only be exceeded by the cool, intrepid manner in which the adventurer conducted himself; and indeed he seemed infinitely more at ease than the greater part of his spectators.”

A second flight from Edinburgh did not go as swimmingly. Lunardi took off from Edinburgh and flew towards Fife but was forced to ditch his balloon in the North Sea. He was eventually rescued by a passing fishing boat.

Lunardi also caught the imagination of the people of Glasgow. He suspended his “Grand Air Balloon” in St Mungo’s Cathedral, charging members of the public one shilling to see it. It was 140 metres-squared in size and was made from yellow, green and pink silk.

The balloon took off from St Andrew’s Square in Glasgow on 23 November, managing a 100-mile flight over Hamilton and Lanark.

Calamity almost struck again at a second Glasgow flight. A local character named “Lothian Tam” supposedly became entangled in ropes attached to the balloon. He unwillingly began to ascend with it. Luckily, he broke free at a low enough height and fell to the ground without serious injury.

![By Kim Traynor [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons A metal plaque set into a stone beside a farmer's field](https://blog.historicenvironment.scot/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Lunardi-plaquenear-Pitscottie-Fife-attrib-By-Kim-Traynor-CC-BY-SA-3.0-httpscreativecommons.orglicensesby-sa3.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons-1024x773.jpg)

A plaque near Pitscottie in Fife, marking where Lunardi made one of his landings (Kim Traynor / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0), via Wiki Commons)

Not everyone was enthralled by the flamboyant aeronaut. Lunardi’s descents in rural areas where a stark contrast to his showy departures in Edinburgh and Glasgow. Farm labourers in Hawick and Fife were reportedly terrified by the sudden appearance of a hot air balloon. They mistook Lunardi’s unexpected arrival from the clouds as a signal for the end of the world!

Do you know any more tales of adventure linking Scotland and Europe? Join in the conversation on social media and tell us what you’ve discovered with the hashtag #ScottishConnections on Twitter and Instagram.