To many residents and visitors walking the streets of Edinburgh, the city’s historic links to the transatlantic slave trade will be far from their minds as they admire the great architecture, soak up the atmosphere and dodge street performers. But Scotland’s capital has a murky past. The Athens of the North had a long and profitable relationship with slavery.

Lisa Williams of the Edinburgh Caribbean Association takes us on a tour of Edinburgh with a difference…

In the heart of the New Town

The statue of Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, towers over St. Andrew Square. As you gaze around this prestigious square, your eyes will fall on several buildings that would have been homes or business premises of Scots who made their fortunes in the transatlantic slave trade. Many of the houses in the New Town were owned by people with investments in the slave trade system.

The monument to 1st Viscount Melville stands at nearly 40 feet tall. To reassure local residents, the lighthouse engineer Robert Stevenson was brought in to advise the project.

It is fitting, perhaps, that this is where we find Dundas. With the immense power he held at the end of the eighteenth century, he was able to use his influence to delay the abolition of slave trade a further 15 years to 1807. Chattel slavery itself was abolished in most of the British colonies in 1834 after a spate of violent uprisings by the enslaved. In order for ’emancipation’ to occur, enslavers were compensated for their ‘property’ to the tune of £20 million and the formerly enslaved forced into an unpaid apprenticeship programme that continued to 1838.

I begin my Black History Walking Tours of Edinburgh at this point. It helps listeners to understand the disproportionate involvement of Scots in not just the East India Company but the slave trade system.

There has been much controversy recently about his statue. What words on his plaque would be appropriate to reflect this unsavoury side of his legacy and give necessary context to his role in Scottish society?

A family affair

The magnificent Royal Bank of Scotland’s headquarters, Dundas House, was the original home of Lawrence Dundas, cousin to Henry Dundas. He owned plantations in Grenada and Dominica.

Occupying a prominent site on the east side of St Andrew Square, Dundas House was built in 1774.

The 4th Earl of Hopetoun, the brother of Henry Dundas’ second wife, and the vice governor of the bank, is immortalised in the bronze statue outside the bank. He was second in command to fellow Scot, Ralph Abercromby, commander-in-chief of the British forces in the West Indies. Together, the men helped to end the two year slave revolution led by French-African Julien Fedon in Grenada in 1795-6 in the fight against the French for islands in the West Indies. Fedon was a highly skilled strategist, and his men executed 40 British, including Scottish governor Ninian Home at his home in Paraclete. After 15 months of fighting the rebels were captured and executed in the Market Square. Yet Fedon was never found. Legend says he escaped to a neighbouring island on a canoe, aided by either the Amerindians or ‘Black Caribs’ in St.Vincent.

The supression of this revolution resulted in slavery continuing for almost another 40 years in Grenada.

An important assembly

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery in Maryland in 1818. After escaping slavery in 1838 by going to New York, he became a brilliant orator and tireless freedom fighter alongside members of his family. After the publication of his 1845 autobiography, ‘Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave’, he lived in Edinburgh in 1846-7 while he made a speaking tour of Britain.

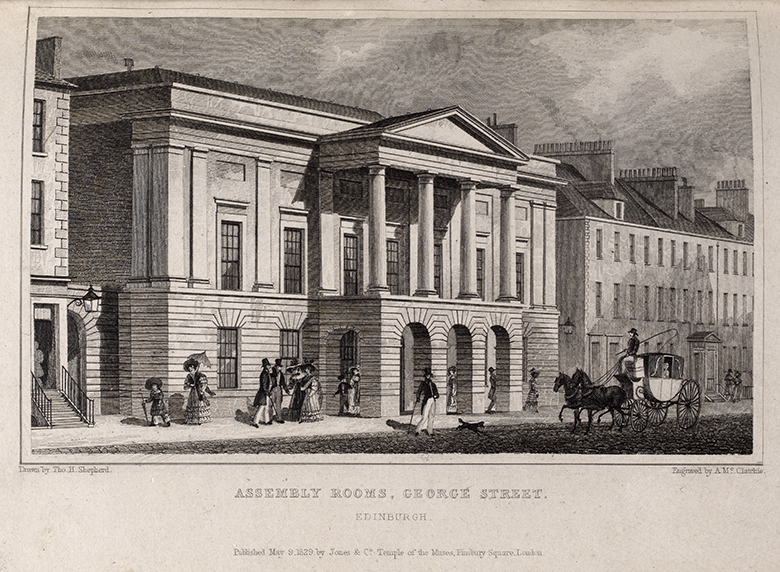

In 1846 Douglass made a famous speech at the Assembly Rooms. Speaking to a packed crowd, he relayed the true story of Madison Washington, an enslaved man fighting for his freedom.

An engraving of The Assembly Rooms from 1829. Artist: A. McClatchie.

Many of his speeches put pressure on the breakaway Free Church to ‘Send Back the Money’ to the slave plantation owners in the Southern U.S. In order to grow the Free Church of Scotland, representatives had visited the Southern States on a fund raising mission. Three thousand pounds was raised from the slave states where the Presbyterian Church was strong.

“They leave their homes and go to the United States, and strike hands in good Christian fellowship with men whose hands are full of blood—the coats, the boots, the watches, the houses, and all they possess, are the result of the unpaid toil of the poor fettered, stricken, and branded slave.” – Frederick Douglass

Although he was unsuccessful in petitioning the leader of the Free Church to change his mind, it raised the profile of the abolitionist cause in America.

Douglass spoke in many places all over Edinburgh and he lived at 33 Gilmore Place over in Bruntsfield, where a commemorative plaque is about to be unveiled.

Having felt so welcome in Edinburgh, he planned to stay, but his wife Anna Murray-Douglass encouraged him to go home and continue to directly fight the cause alongside their fellow African-Americans.

Bute House

Bute House, the official residence of the First Minister of Scotland, has many links to the slave trade.

It was of the 48 houses planned for Charlotte Square. Grander than the other houses in the square, in the 1790s it was home to John Innes Crawford.

Designed by Robert Adam in 1791, Charlotte Square is the crowning achievement of his works.

Born in Jamaica, Crawford had inherited his father’s estates when he was about five years old. This included Bellfield sugar plantation and the several hundred enslaved people who were considered part of the slave plantation estate. The estate had net proceeds of £3,000 a year.

From 1806, Sir John Sinclair of Ulbster took up residence at Bute House. Sinclair was an MP who sat in the House of Commons between 1780 and 1811. He claimed part compensation at the end of slavery in 1833 for the 610 enslaved people living on his estates in St.Vincent, yet died before the payout. It seems he did not make a great impression on his fellow countrymen. Sir Walter Scott described him as an ‘unutterable idiot’ and Henry Cockburn as having ‘accomplished very little, led no party, had no weight.’

Charles Oman bought the property in 1816 from Sinclair and ran it as a successful hotel. Oman also had connections to Jamaica. His son Charles died on the Trinity estate in St. Mary, Jamaica in 1819. This was the same estate that was the site of the famous Tacky’s revolt, an important slave rebellion led by a Coromantee chief from Ghana.

The first Black people in Edinburgh

It’s often quoted that the first mention of an African servant living in a house in Edinburgh is of a man named Oronoce. There’s no solid evidence this was his name but we know he was the servant of Lady Stair and lived in the Writer’s Museum in 1740.

Lady Stair’s House was built in 1622. The Countess of Stair bought the property in 1719.

However, we also know that there were several African men and women present at the Scottish Royal Court in the early 16th century. They enjoyed high status and significant salaries, before the stain of racial slavery created the idea of ‘race’ and racial superiority.

There are many mentions of people of African or Indian descent living in Edinburgh from the late 17th century to the early 19th century. At this time Scots were heavily involved in the slave trade and the East India Company, and it was fashionable for the rich to have an ‘exotic’ servant.

There were certain areas where African/Caribbean people used to get together and socialise with one another. One of them was Jock’s Lodge, where enslaved people were sent as apprentices to learn a trade.

As far back as the 1680s, there is mention of an African man being baptised on the Canongate, the servant of John Drumlanrig.

Malvina Wells, a mixed-race woman employed as a ‘lady’s maid’ was born in Carriacou, Grenada in 1804. Wells was brought to Edinburgh as a teenager with the McCrae family. Her grave is, significantly, the only known grave in Edinburgh of someone who was born enslaved. She worked in the household of Joanna McCrae, other households and independently until her death at the age of 84. She is buried in the McCrae family plot in St. John’s church graveyard.

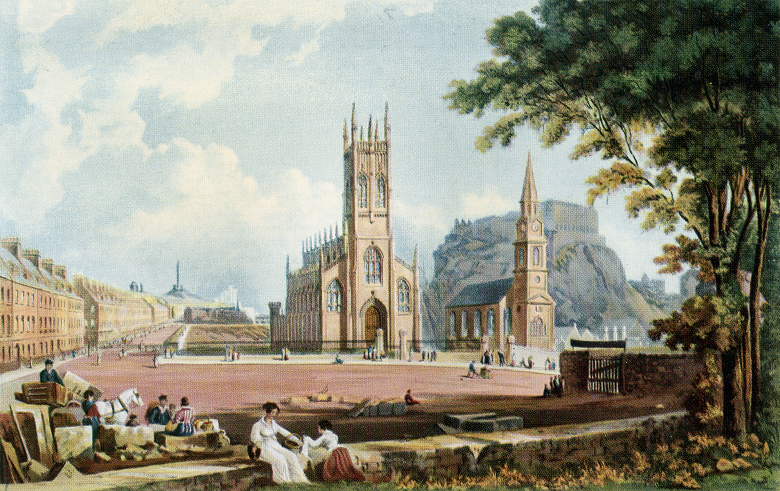

St John’s Church where Malvina Wells is buried. Her grave stone reads “For upwards of 70 years a faithful servant and friend in the family of Mrs MacRae.”

If found…

Even though the Tumbling Lassie case of 1687 had already declared slavery illegal in Scotland, it was still assumed to be legal on Scottish soil. As such, adverts appeared in the papers for both the sale of enslaved people and rewards for the return of runaway slaves. An advert from the Edinburgh Evening Courant, dated February 13, 1727, stated:

Run away on the 7th instant from Dr Gustavus Brown’s Lodgings in Glasgow, a Negro Woman, named Ann, being about 18 Years of Age, with a green Gown and a Brass Collar about her Neck, on which are engraved these words [“Gustavus Brown in Dalkieth his Negro, 1726.”] Whoever apprehends her, so as she may be recovered, shall have two Guineas Reward, and necessary Charges allowed by Laurence Dinwiddie Junior Merchant in Glasgow, or by James Mitchelson Jeweller in Edinburgh.

Fighting for freedom in the courts

Three important cases were held at the Court of Session in which runaway slaves tried to obtain their freedom. Montgomery v Sheddan (1756), Spens v Dalrymple (1768) and Knight v. Wedderburn (1778).

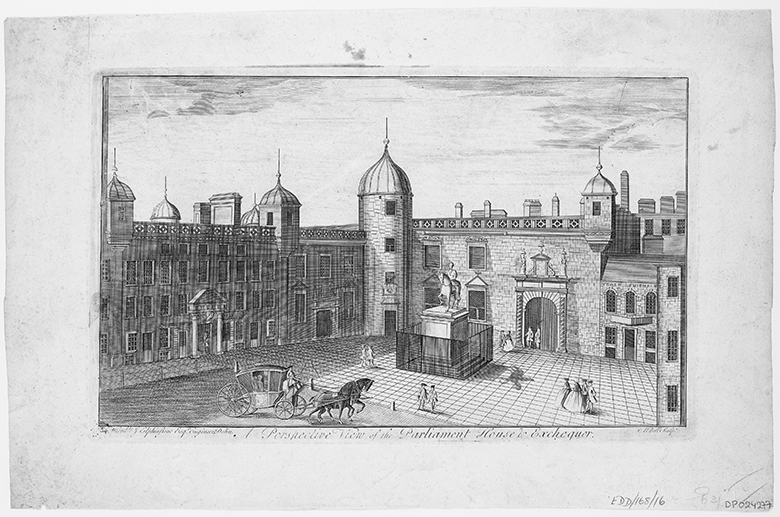

Parliament House, where these cases were heard.

James Montgomery aka ‘Shanker’, was removed from Port Glasgow and put on a ship bound for Virginia. Montgomery escaped to Edinburgh and incarcerated in the Edinburgh Tollbooth Jail. He unfortunately died before his case was decided.

In 1769 David Spens (‘Black Tom’) sued his ‘owner’, Dr David Dalrymple in Methill, Fife for wrongful arrest. Spens had tried to leave his service citing ill health. He had support from local people who helped him to get baptised, and two lawyers fought for his freedom. However, Dalrymple died during the suit which meant Spens automatically became a free man.

In 1778, the Knight v. Wedderburn case became a landmark case in Scotland. Joseph Knight had been taken from the Cape Coast to Jamaica and then brought to Scotland. Knight had a relationship with a woman and argued that he should be allowed to leave domestic service to provide for a family. Knight was influenced by the English precedent of the Somerset v. Stewart case in 1772 which outlawed the forced removal of slaves back to the colonies. Mistakenly, it was widely understood that slavery was abolished on English soil. However, Joseph Knight was successful in arguing that Scots law could not support the status of slavery.

After the case was won, runaway slaves were now protected under Scots law if they wanted to leave service or attempts made to remove them from Scotland to the slave system in the Caribbean. Knight and his wife Annie Thompson, a white servant in the Wedderburn household, mysteriously disappear from the record shortly after the case.

An unhappy marriage

Scotsman Charles Edmonstone went to Demerara (Guyana) in 1780. He married Helen Reid, aka Princess Minda, who was the daughter of an Amerindian chief. At times, Amerindians were also enslaved, worked alongside and had families with African people.

Charles Edmonstone used the forest tracking skills he learned from the Amerindian side of his family to hunt down runaway slaves through the rain forest.

In 1817, Edmonstone brought his wife and their children to Scotland. The marriage began to break down over Minda/Helen’s refusal to let Charles free one of his favoured female slaves. I wonder what the relationship might have been and why it was such an issue? Minda/Helen became addicted to opium and finished her days in seclusion.

Darwin’s teacher

John Edmonstone, originally an enslaved man in Guyana, also accompanied Charles to Scotland in 1817. He moved to Edinburgh and lived at 37 Lothian St. as a free man.

The house where John Edmonstone lived as a free man.

John had learned from the naturalist Charles Waterton and began to teach taxidermy to students at Edinburgh University. In 1826, when Charles Darwin was studying medicine in Edinburgh, he lived just a few doors along from John. Darwin hired Edmonstone at the rate of a guinea a week to learn from him.

As well as taxidermy, Edmonstone was able to teach him about the flora and fauna of South America prior to Darwin’s voyage on the SS Beagle. On the expedition, Darwin collected and preserved finches using Edmonstone’s techniques, a potentially crucial stage in developing his Theory of Evolution.

“Edmonstone was a very pleasant and intelligent man” remarked Darwin. Perhaps such a positive experience with an educated Black man shaped his anti-slavery beliefs? Did the friendship encourage him to develop thinking that challenged the notion of white supremacy in the 19th century? It’s complicated, because in his later work, Darwin went on to propogate an evolutionary hierarchy of peoples that supported racist beliefs.

The plaque to commemorate Darwin is on the outside of a building for all to see. However, there was also one made for Edmonstone. In 2009, a plaque was produced in the style of Josiah Wedgewood’s original anti-slavery porcelain brooches. It was placed at Boteco do Brasil just a few doors along the street. The Wedgwood family were prominent abolitionists and members of Darwin’s extended family. But what has since happened to the plaque? Just over a decade later, none of the staff know where it has gone. If you have any clues to its whereabouts, we’d love to hear them!

Lisa Williams is the Director of the Edinburgh Caribbean Association. She runs Black History Walking Tours of Edinburgh and educational workshops in Scottish schools.

Twitter @edincarib and Instagram @caribscot