Scapa Flow, Orkney, is almost totally encircled by islands that provide shelter from the Atlantic and the North Sea.

It’s sheltered waters have been used as a harbour since prehistory.

A rich naval history has existed at Scapa Flow since the First World War, giving this corner of Scotland a unique, important marine heritage.

The perfect base

It’s strategic position and the expansive but relatively safe waters made Scapa Flow the perfect location for a naval base.

As such, Scapa was chosen as the war station for the British Grand Fleet during the First World War and as the Royal Navy’s northern base in the Second World War.

Although the navy has long since departed Scapa Flow, its legacy survives. Recent surveys are shining new light on the hidden underwater heritage of Scapa and the wealth of wartime history that lies beneath the waves.

Second World War blockship Emerald Wing at Churchill Barrier 2 (courtesy of Scapa Flow 2013 Marine Archaeology Survey)

Wartime history

Many important wartime naval events have strong connections with Scapa.

In June 1916, ships of the Grand Fleet left the harbour before engaging the German navy at Jutland. The following year, Squadron Commander Edwin Dunning landed his Sopwith Pup biplane on the converted aircraft carrier HMS Furious for the first time.

During the Second World War, HMS Hood was dispatched from Scapa on 22 May 1941 to intercept the German battleship Bismarck. In the resulting battle, Hood was destroyed and sank with the loss of 1,415 of her crew.

Scapa also served as the base for the Arctic convoy escorts, one of the most dangerous naval operations of the war.

One of the most famous incident to occur at Scapa Flow took place in June 1919.

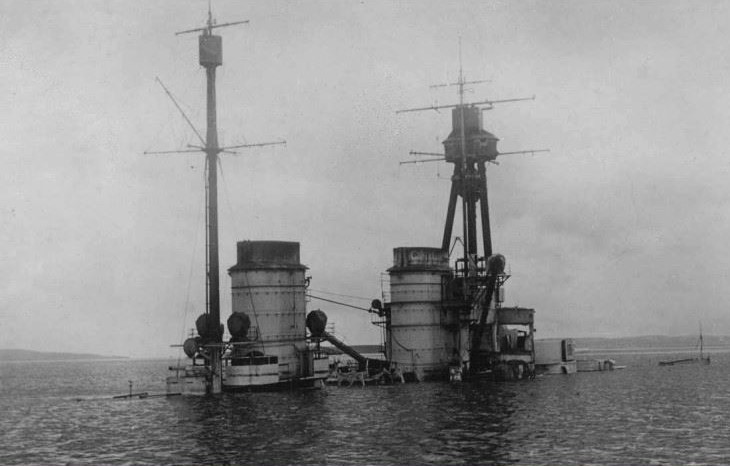

The scuttled battleship Hindenberg (courtesy of the Bobby Forbes Collection)

Scuttling and salvage

At the end of the First World War in 1918, 74 German navy vessels surrendered and were interned in Scapa Flow until a peace treaty could be agreed.

By 21 June 1919 the fleet’s commanding officer, Admiral Von Reuter, had heard the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. To stop German ships falling into enemy hands he ordered the scuttling of the entire fleet.

Despite the intervention of British guard ships, 52 of the 74 surrendered vessels sank.

During the interwar years, almost all of the German wrecks were raised and towed south for breaking. The price of scrap metal was booming as the Second World War approached. It was one of the largest feats of marine salvage of all time.

But not everything could be salvaged…

A diver exploring a section of mast from a German battleship (courtesy of Bob Anderson and MV Halton)

Lost warships

Seven of the scuttled German warships proved too deep to salvage economically in one piece.

The wrecks of three battleships (Markgraf; Kronprinz-Wilhelm; Konig) and four light cruisers (Brummer; Dresden; Coln; Karlsruhe) are all that survive substantially intact.

Elsewhere, the shattered fragments of wreckage of HMS Vanguard bear testament to a huge explosion that took place on 9 July 1917 while the ship was at anchor.

The wreck of the battleship HMS Royal Oak also survives. It is almost intact, but with evidence of torpedo damage inflicted in the early hours of 14 October 1939.

These two Royal Navy incidents claimed the lives of more than 1600 sailors, many buried in the Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery on Hoy.

Hidden underwater heritage

Since the 1980s, the German wrecks have become hugely popular diving attractions.

However, surveys are revealing widespread debris of the many other vessels left behind by the salvors.

The Strathgarry and Chance were among the large numbers of fishing vessels requisitioned for war duties. They were deployed to assist with minesweeping, harbour duties, and the operation of mobile boom defences.

Remains of boom and pontoon defences on Flotta

SS Prudentia was an Admiralty oiler, supplying fuel to the fleet, before she sank following a collision with SS Hermione on 12 January 1916.

The wreck of German submarine UB-116 also lies in Scapa Flow. It is understood to be the last U-boat loss of the First World War.

Some 50,000 tons of redundant merchant ships were sank in the channels as part of a network of defences.

The future

A harbour with a proud naval heritage, today, Scapa Flow remains an important shipping port that is adapting to a future through growth in industries such as marine renewables, aquaculture, fisheries, and tourism and recreation.

We recently consulted on designating a historic marine protected area to help protect this heritage for the future. We’re currently analysing responses from the consultation and hope to submit our final advice to the Scottish Government shortly.