The University of Edinburgh was once a ferocious battleground for women’s rights. Discover how the Edinburgh Seven changed the face of women’s education.

A woman of vision

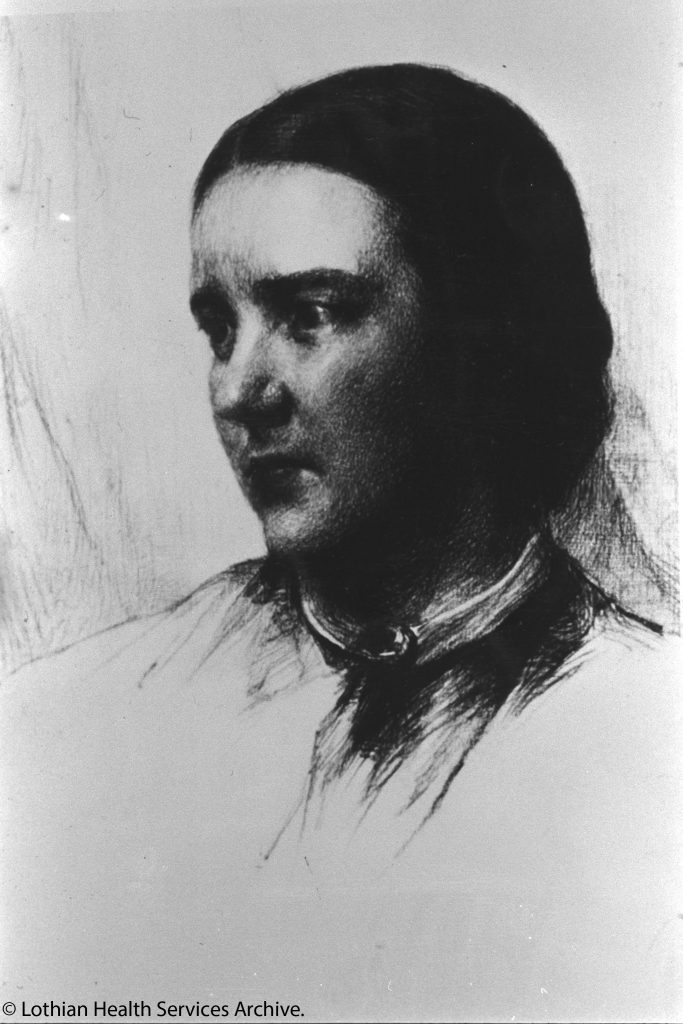

Sophia Jex-Blake was the ring-leader who inspired a group of Victorian women to fight for the right to become doctors.

Sophia Jex-Blake had to fight for equality to follow her dream of becoming a doctor.

Aged 21, Sophia moved to the USA for several years. In the USA, some universities had already begun teaching men and women in the same classes. She was inspired by this approach and even published a paper on the matter.

On returning home in 1868, Sophia decided to pursue a career as a doctor. She knew that it would not be easy to convince a British university to allow her access to study medicine. However, Scottish universities had a reputation for being more progressive and enlightened. Jex-Blake set her sights on the University of Edinburgh.

She applied to study at the University in March of 1869. The University Court rejected her application, saying they could not make the necessary arrangements ‘in the interest of one lady’.

Undeterred, Sophia placed adverts in national newspapers asking for other women to join her in applying to study in Edinburgh. Six more women came forward and they applied as a group. They became known as the Edinburgh Seven.

Meet the Edinburgh Seven

Over the next four years, Jex-Blake was joined by:

Isabel Thorne (1834 – 1910)

Dr Lucy Sewall, an American contemporary, commented that she thought Isabel would have made the best doctor out of the Edinburgh Seven. Isabel dedicated her career to growing the London School of Medicine for Women.

Edith Pechey (1845 – 1908)

While studying in Edinburgh, Pechey came top of the class in the Chemistry exam in first year. She qualified for a scholarship, but her professor feared a backlash and awarded the scholarship to male students with lower grades. After graduating from the University of Bern, Pechey worked as a doctor in India for more than 20 years. She returned to Britain in 1905 and became active in the suffragist movement.

Matilda Chaplin (1846 – 1883)

Chaplin finished her studies in Paris. Afterwards, she moved to Japan where she opened a school for midwives. She also spent time doing anthropological research and published several papers. Chaplin’s daughter Edith Ayrton was one of the founders of the Jewish League for Woman Suffrage.

Helen Evans (1833/34 – 1903)

Evans didn’t complete her studies but continued to be an active member of the group, sitting on the committee of the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women. She married Alexander Russel, editor of The Scotsman newspaper. Their daughter Helen Archdale became a prominent suffragist and feminist campaigner.

Mary Anderson (1837 – 1910)

Anderson was the only Scottish member of the Edinburgh Seven. She completed her studies in Paris and became a senior physician at the New Hospital for Women in London.

Emily Bovell (1841 – 1885)

Like many of her peers in the Edinburgh Seven, Bovell completed her studies in Paris. She also worked at the New Hospital For Women, along with Anderson. In 1881 she moved to Nice and established herself as the first woman doctor there.

The group application was approved and the University of Edinburgh became the first British university to admit women. But the struggle was not over!

Bullying, harassment and riots

One year into their studies, the women were set to attend an anatomy exam at Surgeons’ Hall. When they arrived to sit their exam, they were confronted by an angry mob. Several hundred students and onlookers blocked their entry and hurled abuse, mud and refuse at them. But the Edinburgh Seven were determined to get in. Contemporary records suggest that either the university janitors or a small group of fellow students helped them bypass the mob.

The Surgeons’ Hall Riot attracted widespread publicity and created a groundswell of support for the women’s campaign.

Inside the exam hall, protests from male students continued and several were thrown out of the exam. A live sheep was even released into the hall to disturb the students.

While the women were able to sit this exam, the barrage of bullying and harassment continued. To add insult to injury the University refused to allow the women to graduate. In 1873 the Court of Session upheld the university’s decision and ruled that the women should never have been admitted in the first place.

Picking up the pieces

Showing a huge amount of resilience, five of the women (including Sophia) went to Europe to complete their degrees and receive their qualifications. It wasn’t until 1892 that Scottish Universities would once again admit female undergraduates.

In 1878, Dr. Sophia Jex-Blake returned to Edinburgh and became the city’s first female doctor. She set up her own practice on Manor Place in the New Town.

She was keen to provide medical care to poorer women in the city and set up a clinic in Grove Street in Fountainbridge. The clinic provided relatively cheap medical care for women and offered practical experience to young female doctors at the same time.

Over the years the clinic expanded, and was renamed the Edinburgh Hospital and Dispensary for Women (later becoming the Bruntsfield Hospital). This was Scotland’s first hospital for women staffed entirely by women.

This photo from the 1920s shows a mother and children at Grove Street Dispensary.

Turf wars

In 1886, Jex-Blake founded the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women. This venture took some of the sheen off her trailblazing work. Unfortunately, Jex-Blake gained a reputation as a rather harsh disciplinarian. She was sued by sisters Grace and Georgina Caddell after they felt they were unfairly expelled from the school.

In 1889, Elsie Inglis (a former student of Jex-Blake) founded the Edinburgh College of Medicine for Women. A number of students left Jex-Blake’s establishment to study under Inglis.

In 1899, Jex-Blake retired to East Sussex with her romantic partner Margaret Todd, who was an author and doctor. Todd was one of the first student’s to attend the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women and coined the scientific term “isotope”.

Legacy

Dr. Sophia Jex-Blake’s determination paved the way for women to pursue professions which were previously closed to them. Along with the other members of the Edinburgh Seven, she championed the rights of women to follow a career of their choosing. Their contribution was recognised in 2015 with a plaque erected at Surgeons’ Hall.

This plaque outside Surgeons’ Hall commemorates the Edinburgh Seven.