Before the nineteenth century development of the railway in Britain, and the opening up of historic monuments as visitor attractions, people didn’t undertake tourist trips in the way we do today.

Two female writers at the turn of the nineteenth century were among the first to do so in Scotland.

Intrepid Women: Murray and Wordsworth

Sarah Murray (1744-1811) was a travel writer, based in London, who wrote one of the first guidebooks published in English. In 1796 she undertook a five month tour of Scotland by carriage with a maid and a manservant.

Three years later she published A Companion, and Useful Guide to the Beauties of Scotland, to the Lakes of Westmoreland, Cumberland, and Lancashire (1799). In it Murray described how,

I think I have seen Scotland, and its natural beauties, more completely than any other individual. I took great pains to see every thing worth seeing”.

Dorothy Wordsworth (Image source: Wikimedia Commons)

Her contemporary Dorothy Wordsworth (1771-1855) visited Scotland in 1803 and 1822. Originally from Cumberland, Dorothy was the sister of the poet William Wordsworth. The pair were very close: he accompanied her on the 1803 trip.

Her journals were intended for friends to read and so were only published in complete editions in the twentieth century. Volumes one and two concern her travels in Scotland: Journals of Dorothy Wordsworth, ed. E. de Selincourt (1941).

The writings of these two intrepid women have much to tell us about the interests and perceptions of travellers of two hundred years ago. What’s more, many of the attractions that they visited are now in the care of Historic Environment Scotland, meaning that we can follow in their footsteps today.

Breakfast-less at Bothwell

Bothwell Castle, c.1860

Murray and Wordsworth were attracted to the picturesque qualities of historic sites, valuing the combination of romantic ruins and natural beauty. Both visited Bothwell Castle in Lanarkshire. An apparently tired and hungry Murray recorded how,

by a rich feast of beauty and nature, I forgot the din of Glasgow, its pride, its wealth, and worldly ways; forgot my sleepless night; even hunger too (for I had not breakfasted) gave way to the delight of the scenes of Bothwell afforded me.

What a lovely walk is that by the river’s side! How picturesque the ruin, and the wood! How enchanting the scene from the windows of the house!”

However, her appreciation was marred by the neatly manicured grass lawns and flower borders, which she thought “out of place”. Wordsworth likewise was taken aback by “the unnaturalness of a modern garden”, noting that,

If Bothwell Castle had not been close to the Douglas mansion we should have been disgusted with the possessor’s miserable conception of adorning such a venerable ruin; but it is so very near to the house that of necessity the pleasure-grounds must have extended beyond it.”

New Bothwell Castle, described by Wordsworth as ‘the Douglas mansion’. It was demolished in 1926

Paving the streets of London

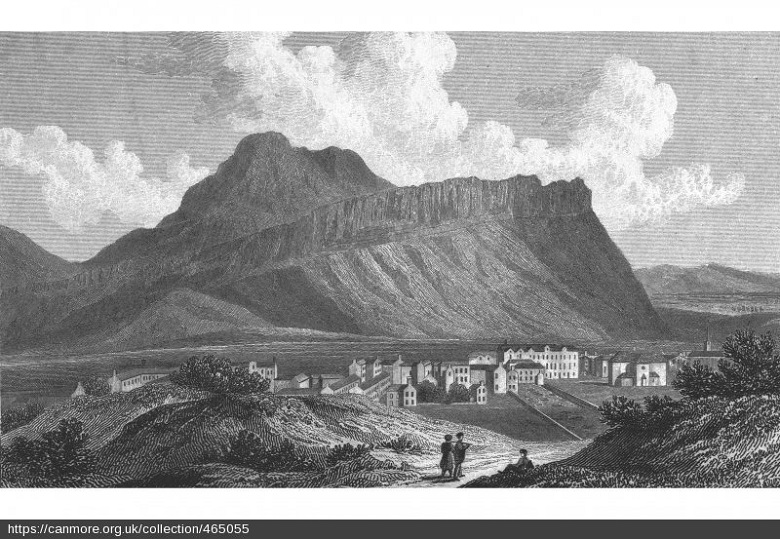

The writings of these early tourists show how the uses of historic sites have changed over time. On Murray’s visit to Holyrood Park she noted the quarries at Salisbury Crags at which

I saw vast heaps of the hard rock divided into small pieces, ready for shipping; and I was told great quantities of that crag were sent to London for paving the streets.”

Quarrying at the park reached a peak in the early nineteenth century. It was stopped in 1831 in order to prevent further changes to the appearance of the crags.

Arthur’s Seat and Salisbury Crags, Edinburgh, as they appeared in 1829, two years before quarrying in Holyrood Park ceased

Stop! Who goes there?

Then, as now, historic sites were not static places but had continuing lives, uses, and inhabitants. Murray visited Fort George near Inverness, which has been a military base since the 1750s. As her carriage approached the gate, sentinels shouted, “Stop! Who goes there?”

After giving her name she was allowed to enter and,

though I was entirely unknown at the fort, the lieutenant-governor, with the utmost politeness, sent an officer to conduct me over every part of the fortification, and to show me everything I was capable of noticing.”

Fort George is still an army base today, but visiting is much easier than Murray found!

The entrance to Fort George used by Sarah Murray in 1796 and still welcoming visitors today.

Something fishy at Dumbarton

At Dumbarton Castle Wordsworth was likewise guided around by a resident soldier, noting that, “we looked over cannons on the battery-walls, and saw in an open field below the yeomanry cavalry exercising.”

She saw soldiers’ wives, “hanging out linen upon the rails, while the wind beat about them furiously.” Sheep were grazing on Dumbarton Rock, “pursuing their natural occupations.” They were not the only animal inhabitants of the castle, however.

The soldiers also showed them a trout, which had supposedly been kept in a well for more than thirty years:

For the pleasure of the soldiers, who were anxious that we should see him, we took some pains to spy him out in his black den, and at last succeeded.

It was pleasing to observe how much interest the poor soldiers seemed to attach to this antiquated inhabitant of their garrison.”

Dumbarton Castle and its prominent position on Dumbarton Rock, circa 1718

All kinds of guides

In these early days of tourism, there was a wide variety of people who would show visitors around. Often visitors would make use of bilingual guides who acted as Gaelic interpreters. In Perthshire, Murray employed a boy of about twelve years of age to show her around.

At Dryburgh Abbey Wordsworth was met by an “ancient woman [who], by right of office, attended us to show off the curiosities”. Living in a nearby thatched hut, she was “bowed almost double, having a hooked nose and overhanging eyebrows, a complexion stained brown with smoke.”

Dryburgh Abbey on a sunny day. Dorothy Wordsworth was shown around by an “ancient woman” from a thatched hut.

In contrast, at nearby Melrose Abbey Wordsworth bumped into historical novelist Walter Scott, who “was here on his own ground, for he is familiar with all that is known of the authentic history of Melrose and the popular tales connected with it. He pointed out many pieces of beautiful sculpture in obscure corners which would have escaped our notice.”

Walter Scott pointed out Melrose Abbey’s hidden stone carvings

These days you are more likely to encounter our friendly and knowledgeable staff around our sites. They are more than happy to show to the modern tourist ‘every thing worth seeing’.

Ready for an adventure? Head to our website to explore hundreds of historic places.