Take a leisurely stroll through the history of three gorgeous Scottish gardens with us.

Lydia’s Garden at Hugh Miller’s Birthplace Cottage and Museum, Cromarty, Highland

Lydia’s Garden sits behind this humble thatched cottage. It’s the birthplace of fossil hunter, folklorist, stonemason and social justice campaigner, Hugh Miller.

He was born in the port town of Cromarty in 1802. The son of a ship owner who died at sea when Miller was only five years, Miller was raised by his extended family. He left his formal education after a fiery dispute with the head teacher, but continued to grow his knowledge of geology and love of the landscape from long walks along the shoreline of Easter Ross and apprenticeship as a stonemason.

Hugh Miller. © Scottish National Portrait Gallery. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

In the 1820s, he began to write and to publish. Following successful series on the herring fishing industry and a less successful volume of poetry, he made his first major breakthrough on the literary scene with ‘Scenes and Legends of Northern Scotland’, a collection of folklore and tales of Highland history that’s still widely celebrated today.

The Lydia that the cottage garden is named after was Miller’s wife. Despite her family’s objections, Lydia Mackenzie Falconer Fraser and Hugh Miller married in 1837 after a five year engagement. Together they had four children, but by 1840, Miller was caught up in his work around social and religious controversies and moved to Edinburgh.

Miller’s wife, Lydia. © The National Trust for Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

The subjects of his influential essays included the impact of the Clearances on the rural Highland communities, critiques on urban working conditions and increasingly fierce debates on the Disruption of the Church of Scotland, leading to the Free Church of Scotland being established in 1843.

Miller worked as editor for The Witness newspaper and was instrumental to its success. Under his guidance, circulation soared. He used his influence to become a leading figure in the Disruption which saw almost five hundred ministers leave the Church of Scotland to form the Free Church.

© National Trust for Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

His religion played a huge role in his life but it’s clear that there was conflict between his scientific discoveries and his traditional Presbyterian beliefs. Whether due to the pain of a physical illness from his early days as a mason or the struggle in reconciling his beliefs, Miller suffered from severe mental distress and Victorian attitudes towards treating mental health did not help. In 1856, he shot himself at his home in Portobello and died on Christmas Eve.

The intellectual world was shocked by his death. Without any academic credentials, he left a huge legacy. Lydia, herself a writer of children’s books, played a major role in editing and posthumously publishing many more of Miller’s writings.

The dialstone in the garden of Hugh Miller’s House. Hugh carved the dialstone during his time as a stonemason. © National Trust for Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

Today, the National Trust for Scotland keeps his birthplace open as a museum and in the centre of Lydia’s Garden sits an ornately carved sundial that Miller made for his uncles who inspired his love of folklore and flora and fauna.

Amisfield Walled Garden, Haddington, East Lothian

This unassuming gateway is actually an entrance to one of the largest walled gardens in Scotland.

The Amisfield Walled Garden was designed by John Henderson in the 1780s with a dual purpose. It needed to both entertain guests of Francis Wemyss-Charteris, the 7th Earl of Wemyss, and to provide a constant supply of fresh fruit and vegetables for the Earl’s mansion, Amisfield House.

The result was eight acres of garden surrounded by 16 foot walls punctuated with impressive classical pavilions to reflect the enormous wealth of its owner.

The 7th Earl of Wemyss took his title following his elder brother’s implication in the Jacobite Risings. David Wemyss, Lord Elcho and the 6th Earl, had been one of Prince Charles’ advisers and supported him in his attempts to reclaim the throne. Following the collapse of the Jacobites, he was forced to forfeit his titles and estates under a piece of legislation called an attainder. His brother Francis claimed them as heir, though he was never formally acknowledged due to the attainder.

The civil war divided families and communities. Looking at the views from above, I can’t help but think the garden hints at a similar story between the Wemyss brothers – the distinctive ‘Union Jack’ layout of the paths in the garden is unlikely to have been an accident so soon after his family had been officially stripped of their titles.

In the years that followed, Amisfield House and the parkland surrounding it were home to a variety of different uses, including the Tyneside Games held annually between 1833-1853, a golf club established in 1865 and a military training camp for officers in throughout World War One.

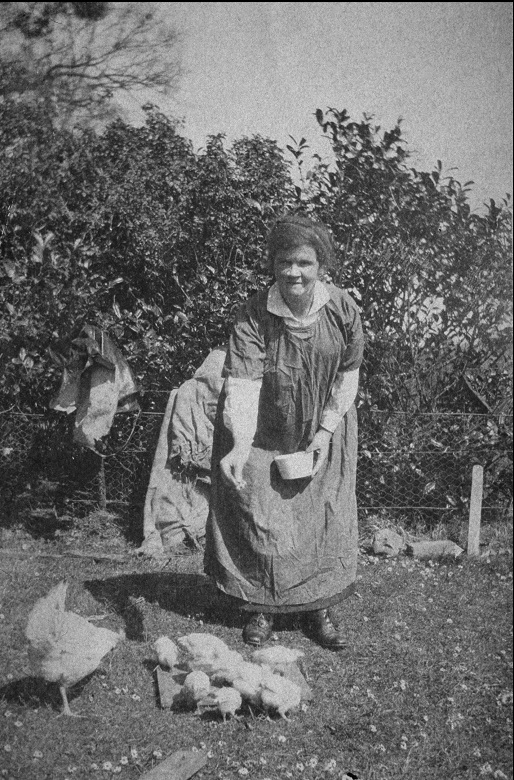

After the war, Amisfield House lay empty for a number of years. Mrs Paterson, with her husband Jim, acted as caretakers to the house until its demolition in the 1920s. One huge estate, a large house and one of the biggest walled gardens in Scotland was a lot for two people to look after!

Mrs Paterson scattering some feed to some hens and chicks in the grounds of Amisfield House. © East Lothian Museums Service. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

Much of Amisfield House’s sandstone was reused in and around Haddington after the demolition and the garden operated as a market garden and as arable land during World War Two.

The Wemyss family sold the park in 1969 and in 2013 the Amisfield Preservation Trust was granted a 99-year lease on the garden. Over the past 12 years, the Trust’s hardworking volunteers have restored it from a neglected state into a vibrant community garden.

Royal Botanic Gardens, Edinburgh

The origins of these huge gardens in Edinburgh date back to 1670, making them the oldest botanic gardens in Scotland and the second oldest in the UK after Oxford.

They first began as a physic garden in the grounds of Holyrood Abbey thanks to two adventurous doctors, Robert Sibbald and Andrew Balfour, who would later go on to found the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

They leased a plot no bigger than a tennis court and convinced local physicians to contribute to the cost of the “culture and importation of foreign plants”. Six years later, needing more space, they moved the gardens to a plot at the top of Edinburgh’s Nor Loch. Today, you’d be standing on Waverley Station’s Platform 11 – keep an eye out for the blue plaque next time you pass through Edinburgh’s central train station!

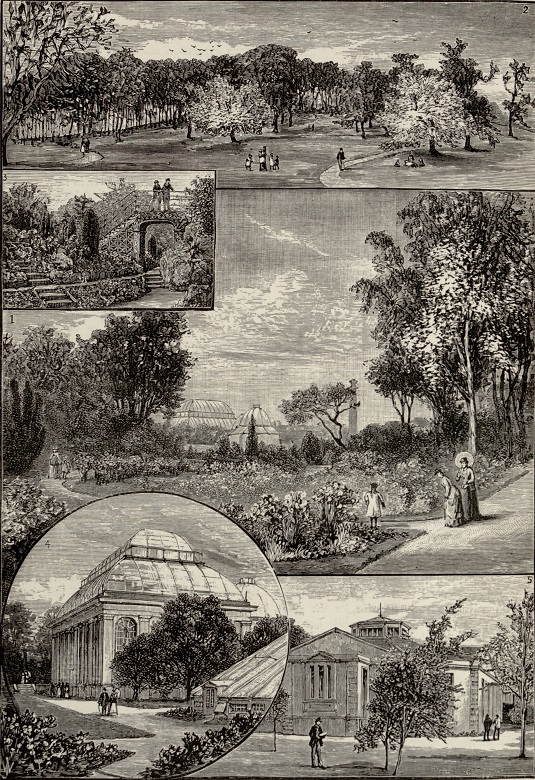

A 19th century engraving showing the Royal Botanic Gardens. © National Museums Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

The collection of plants expanded along with the British Empire and in 1763, the gardens relocated out of the city centre to a ‘green field’ site near present day Leith Walk. The final move to Inverleith started in 1820. Relocation to the 116-hectare site took three years and some impressive ingenuity to move every plant and mature tree. The Curator of the gardens, William McNab, even invented a transplanting machine!

The hot houses in the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, 1967. © The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

The glasshouses standing today were built in phases between 1834 and 1978, with the Herbarium and Library building opening in 1964. This building was extended in 2005 to make more space for one of Europe’s largest botanical libraries and the collection of around three million preserved plant and fungi specimens.

Today, the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh delivers world-leading plant science, conservation and education programmes and welcomes over one million visitors every year.