Mungo Park was a Scottish explorer of West Africa. His expeditions predate those of David Livingstone by over 40 years and it would probably be fair to say that his name is not as well kent as that other famous Scot.

Therefore, if you’ve ever visited Selkirk and aren’t familiar with the story and legacy of Mungo Park, you might have been surprised to see a memorial to him which incorporates representations Black people in the heart of a town in the Scottish Borders.

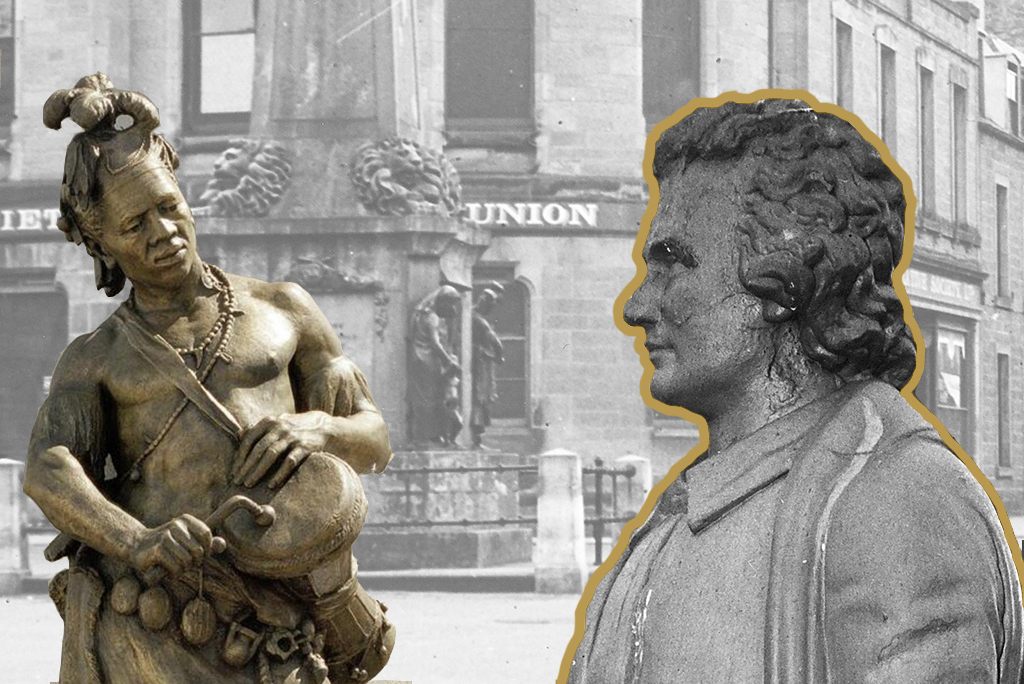

An archive photo of Mungo Park’s memorial, dating to around 1930. You can zoom in on the image on Canmore. © Scottish Borders Archive & Local History Service, courtesy of Robert D Clapperton Trust

This monument is, of course, part of Scotland’s colonial legacy. It’s a complex legacy and there’s no straightforward answer to how we acknowledge and engage with it. At Historic Environment Scotland we’re having these discussions all around the organisation, in relation to all sorts of work. Scotland’s colonial legacy impacts the work of every member of staff.

If you’re planning to read on, please be aware that this blog includes quotes which feature language that is discriminatory.

Acknowledging Scotland’s legacy

In our Designations Team, which looks after information related to Scotland’s listed buildings and monuments, work is ongoing to figure out how we can provide a more informed picture of Scotland’s role in the British Empire and how it shaped the streets and landscapes around us.

We have over 55,000 records of scheduled monuments, listed buildings, gardens and battlefields. We’ve sought to eliminate terminology which is immediately recognised as offensive. However, we recognise that reflecting the complexity of history and the legacy of Scotland’s colonial activity is a much bigger task.

However, we know this is just the start of a much longer process. What’s needed now is an examination of how we provide more detail on the subject of the Empire. This is very much a work in progress and something we’re happy to engage with a broad range of stakeholders on.

A brief history of Mungo Park

Mungo Park was born in Selkirkshire on 11 September 1771. His father was a fairly well-off tenant farmer who worked land belonging to the Duke of Buccleuch.

Mungo Park’s family home in Foulsheils. © Scottish Borders Archive & Local History Service, courtesy of Robert D Clapperton Trust

Park enjoyed a relatively privileged upbringing. He received a good education and enrolled at the University of Edinburgh, where he studied medicine and botany.

When he completed his studies in 1792, Park became an assistant surgeon on a ship belonging to the East India Company. His first voyage, which took place in 1793, was to Benkulen in Sumatra.

Park had been recommended for the East India Company job by Sir Joseph Banks, a prominent naturalist and botanist. Banks had served on Captain James Cook’s first voyage (1768–1771) and was lauded upon his return.

Headed for the ‘unknown interior’

In 1794, Banks once again recommended Park for an expedition. The young medic and botanist had applied for a post with the Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa, more commonly known as the African Association. His mission was to discover the course of the Niger River.

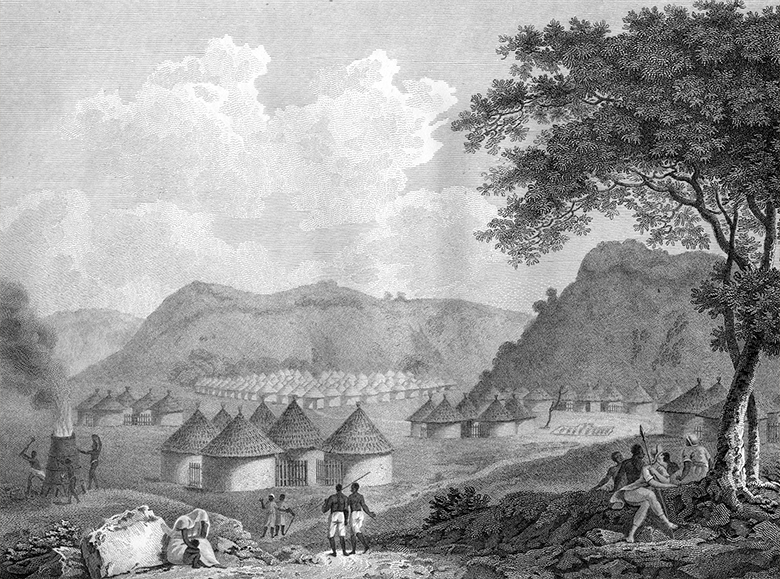

On 22 May 1795, Park left for his first expedition to West Africa. You can read Mungo Park’s detailed account of his expeditions in his Travels in the Interior of Africa on Project Gutenberg. It is truly a fascinating read. However, as you might expect, the text is very much of its time. It contains material which is racist and colonialist in nature, so reader discretion is advised.

“View of Kamalia in Mandingo country, Africa” from ‘Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa’. Image via Wikimendia Commons.

Preparation is key

Park left on his second expedition to West Africa at the start of 1805. In the years between his two expeditions, he had lived in Peebles and worked as a doctor. In that time, he met and befriended fellow local celebrity, Sir Walter Scott. At the time of their acquaintance, the young men were both in their early 30s.

In preparation for his expedition, Park also invited a man called Sidi Ambak Bubi to live in Peebles and teach him Arabic. In his biography of Mungo Park, the Scottish author Lewis Grassic Gibbon provides this colourful description of Bubi’s reception in Peebles:

Mungo sought round London for an Arabic tutor. Presently he laid hands on him in the person of a stray Moor, one Sidi Ambak Bubi, a pallid man shivering in the sharp blow of London March. He was to shiver with considerable more intensity in a week or so. With Mungo he journeyed up to Peebles, where his advent woke that somnolent borough to interest for the first time in its recorded history. Peebles ran and gaped and stared much as the African villages had done at sight of Mungo. The Sidi’s opinions of his reception are not recorded.

The ill-fated expedition

On his second West African expedition, Park was accompanied by two fellow Borderers. His brother-in-law Alexander Anderson and the draughtsman George Scott were recruited to the party.

In this mission, Park was determined to prove his theory that the Niger river and the Congo were one and the same. (They are not!)

In total, over 35 Europeans left from Portsmouth with Park. They landed in Senegal and travelled east, over land, until they met the Niger river. By the time they reached the Niger, only 11 were left alive. Disease had killed over two thirds of the group.

The much reduced party made their way up the Niger by canoe. Isaaco, a guide who was a member of the Mandingo people, accompanied the group as far as Sansanding, over 700 miles from their starting point. The letters he returned with were the last direct communications from Mungo Park’s expedition.

Isaaco left an even smaller group to continue on up the Niger. By this time the remaining group consisted of “Park, Martyn, three European soldiers (one mad), a guide and three slaves”, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica of 1911.

When nothing further was heard from Park, the British government commissioned Isaaco to investigate. He returned to the point where he’d left the group and spoke to the guide who had taken over.

The guide described a journey fraught with danger and violent altercations. Park had adopted a policy of not engaging with the people that they encountered on their journey. His approach was “shoot first”.

Eventually, surrounded by a group of armed men under the orders of a local chief, their boat hit a rock in some rapids. The boat was stuck fast. Under heavy fire from the riverbank, Park and others in his party abandoned ship and were drowned.

A complex relationship

Although there are more than a few sympathetic portrayals of Black and enslaved people amongst his writings, Mungo Park did not advocate an end to slavery.

A quote that is often used to show Park’s admiration for Black people is:

whatever difference there is between the negro and European, in the conformation of the nose, and the colour of the skin, there is none in the genuine sympathies and characteristic feelings of our common nature.

However, Mungo Park’s biographer, Christopher Fyfe noted:

What was to disconcert (and still disconcerts) some readers was the detached way in which Park wrote not only on slavery but on the slave trade (in which indeed he had been a participant), presenting them without condemnation as established social institutions. Of the proposed abolition of the trade, then an active political issue, his only comment was, ‘my opinion is, the effect would neither be so extensive or beneficial as many wise and worthy persons fondly expect’

Mungo Park’s Memorial

Although Park died in 1806, it was another 53 years before a memorial to the explorer appeared on the High Street of Selkirk.

Over the years, this category B listed monument has seen some interesting changes.

The original designs for the monument were made by Andrew Currie. Currie was a noted sculptor and antiquarian from the Scottish Borders. According to some reports, Currie was a relative of Mungo Park. You might be familiar with other examples of his work if you’ve seen the James Hogg memorial at St Mary’s Loch or admired the statue of Robert the Bruce at Stirling Castle.

Andrew Currie carved the King Robert I statue at Stirling Castle.

The original designs

In June 1858, a reporter in the Teviotdale Record and Jedburgh Advertiser described Currie’s designs for the monument. Park was to be atop a pedestal adorned with bas reliefs on each side and figures on each corner.

The figures were to be a White man and woman and a Black man and woman. The descriptions of the designs can tell us a lot about the attitudes of White people towards Black people in the Victorian era. Some of these attitudes persist today.

“Her ugly, kind, affectionate face is in expression beautiful in spite of itself,” is the description we’re presented with for the Black woman. By contrast, the White woman is “sweet, beautiful, and with the grace of well-formed, well-exercised limbs.”

Similarly, the Black man is described as “a brawny African, with his lion’s skin swung from his shoulder; he has a powerful, royal look—ugly and grand, and with that melancholy which is the habitual expression of our dark brethren.” Whereas the White man is “a border shepherd—tall, handsome, with mind and energy”.

The further four panels would have represented scenes from Park’s life.

At this time, it seems the funds could not be raised to pay for the elaborate designs around the pedestal. The memorial was erected without them.

This photo, taken some time between 1880-1900, shows the monument before the additional plaques and figures were added. Take a look on Canmore. © Courtesy of HES (Whytock and Reid Collection)

We’ve started, so we’ll finish

In the decades that followed the initial unveiling of the monument, regrets were expressed that it had been left unfinished. Ahead of the centenary of Park’s death, the local community came together to decide what should be done to mark the occasion.

Some suggested a bursary in Park’s name to provide “help for a poor lad or poor girl get a university education which would fit them for higher work”. Others were keen to see Alexander Anderson and George Scott, the other two men from the Borders who lost their lives on Park’s expedition, remembered too. The most popular idea seems to have been the completion of the memorial. Newspaper reports from the time suggest that Currie’s original designs were misplaced.

Ultimately, the committee decided to commission a new sculptor to design and create the new panels. They also supplied a new brief. They decided that the four figures should represent “the four tribes with whom Park came in contact in his travels in South Africa.” (sic)

They resolved “that two panels (descriptive scenes Africa connected with events in Park’s life) be placed on the monument. They also decided to add an inscription on the west side of the pedestal. This was to include the names of Alexander Anderson, George Scott, and young Park. (Mungo Park’s son.)

A coveted honour

The job went out to tender. One Edinburgh sculptor quoted a price of £400 to deliver two panels. However, local sculptor Thomas J. Clapperton offered to do the work for just £100. He explained: “The price is low, but it may prove to the committee genuine interest I have already expressed, and my desire to do it, is not for gain, but on sentimental grounds.” He also said: “Being a Borderer myself, I covet the honour of thus helping to commemorate one of our greatest men.”

Clapperton was taken on to provide the panels. However, there was not enough money for him to carry out the four figures at this stage. These were added in 1913 after the money was raised.

You may be familiar with Clapperton’s other work if you’ve ever looked up at the statue on the top of the Mitchell Library in Glasgow or spotted Robert the Bruce at the Edinburgh Castle gatehouse. (Fun fact: William Wallace, on the other side of the gate, was designed by fellow Scottish sculptor Alexander Carrick.)

Thomas J. Clapperton made the statue of King Robert I at Edinburgh Castle.

In 1971, the monument was listed at Category B.

How we talk about the Mungo Park memorial

How we feel about the things in our environment can adapt over time as our cultural values and understandings change with the times. As we’ve already seen in this blog, things are not the same as they were 200 hundred years ago when Mungo Park was undertaking his expeditions. They’re not even the same as they were 100 years ago when the people of Selkirk were looking to commemorate their local hero.

What we think about our past isn’t set in stone. Therefore it is right that we reexamine and build new relationships with the historic environment around us. This helps to keep it alive and relevant for new generations to come.

Many of our designation records were written many years ago and we know that some records contain descriptions or terminology that we would not use today. We will always remove offensive words in our records when we become aware of them. The Mungo Park monument was first listed in 1971. Back in 2019, after a visit to Selkirk, one of our designations team spotted the use of the word ‘Negro’ in our listing. That was quickly updated.

One of the most exciting things about history is that it’s constantly evolving and changing. Mungo Park’s monument is a really good example of this. Over the centuries so many things about it have changed: the monument itself, the language used in the documentation, our understanding. Ongoing research and interpretation continue to add new context. That is something we should continue to embrace and celebrate.

Banner images credit: © Scottish Borders Archive & Local History Service, courtesy of Robert D Clapperton Trust