What do you see if you’re asked to picture a young Scottish aristocrat from the turn of the 19th century? Would he have Black heritage? Would he be disabled? James Duff, who was born in 1758, was a member of one of the most privileged families in Scotland . He was also a disabled man with Black ancestry.

Picking through the past can help us to see a diverse history. Amongst family letters you can often discover parts of history that have been forgotten or deliberately erased.

In this blog, we’ll share what we know of James’s life. This information generally comes from letters written by people who knew James. Some of the descriptions they use are offensive and outdated, so reader discretion is recommended.

James’s wealthy roots

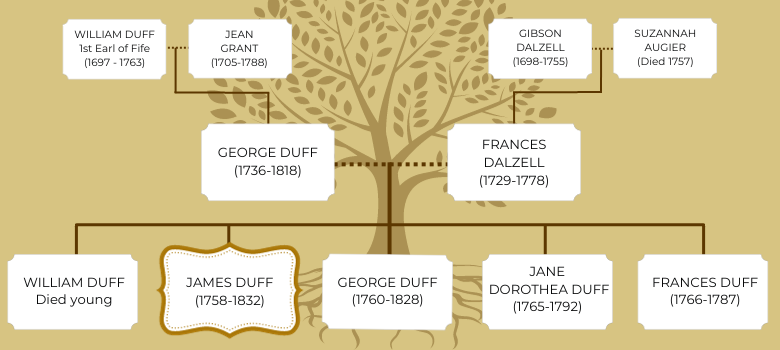

James Duff, sometimes Jem to his family, was the eldest surviving son of George Duff and Frances Dalzell. George and Frances were married in 1757.

George was the fourth son of Jean Grant and William Duff (1st Earl Fife), who commissioned the building of Duff House in Banff.

We don’t know whether James ever visited his family at Duff House.

Meanwhile, James’s mother Frances was the daughter of Gibson Dalzell and Susanna Augier. Gibson was the owner of Lucky Hill, a sugar- and rum-producing estate in Jamaica. Susanna was a formerly enslaved woman. Frances brought considerable wealth to her marriage, having inherited half of her father’s property, which included enslaved people.

The pair settled in fashionable London. Frances had allegedly refused to live in Scotland. Her brother-in-law, Alexander, wrote that:

‘English ladies have unreasonable prejudices against our northern region, which they with difficulty ever get over.’

Brothers and sisters

Frances and George had five children: William (died young), James (1758-1832), George (1760-1828), Jane Dorothea (1765-1792), and Frances (1766-1787).

Young George embarked upon a military career but racked up gambling debts and had a scandalous affair with a married woman.

Jane Dorothea suffered from ill health. For a time, she lived at Rothiemay in the north-east of Scotland with her grandmother, the dowager countess Fife. Later, she kept house for her father in London. She was said to be an intellectually gifted child, ‘who reads English and French extremely well, speaks both languages very easily, writes and counts to admiration, and is […] very good at her needle’.

The ruins of Rothiemay Castle, photographed in 1963, before it was demolished in 1964. © Crown Copyright: HES (Scottish National Buildings Record).

Young Frances was a family favourite, also brought up by their grandmother. She received gifts of cards, books, and ‘provision for her birds’ from her adoring family.

James’s childhood

James’s upbringing, however, was markedly different to those of his siblings. His place in the family, or lack thereof, was determined by his disability. It is impossible to know the exact nature of this disability from the evidence available. Letters written by people who knew James include their impressions of him. It seems likely that James had a learning disability.

In an undated letter, Frances wrote that:

‘Jem just now read to me, good gods ! how he does read. He is a riddle, I hope some sensible man will expound him.’

Although expressing surprise at James’s ability to read out loud, in the same letter Frances described how:

‘The children are well, and they give us many agreeable hours, indeed in this place their company makes us very happy’, showing that James was loved by his parents.

Books in the library at Duff House.

A life in care

Despite this, it was considered best that James live apart from his family, to be cared for by professionals. At that time, although many people with disabilities lived successfully within their own communities, some people with mental illnesses and learning disabilities were housed in asylums. In 1828 William Maule, the surgeon of Beaufort House in London, wrote the following:

‘I hereby certify that the person designated as Mr. James Thompson and alluded to in the accompanying certificates, is in reality James Duff the eldest son of the Honourable George Duff of Elgin; that fifty-seven years ago he was placed in the establishment called Beaufort House where he still is, under the superintendence and management of my late father, who as an intimate friend of the late Hon. George Duff undertook the guardianship of his idiot son, that as a matter of delicacy and family feeling, or from other motives the origin of which I am not acquainted with, he was nominated James Thompson, under which name he has ever since been known; that since the death of my father, thirty years ago, I have executed the same office of friendship by watching over the well-doing and proper treatment of the said James Duff, otherwise Thompson, and that I have regularly paid for his support, maintenance and clothing, such sums as his late father appropriated and were found sufficient for that purpose. Finally, I certify that I saw him a few days ago (June 29), when he was still in the same hopeless state of fatuity in which I have seen him for the last forty years upwards, that his infirmity is irremediable, and that he is in every way incapable of managing the most ordinary affairs.’

James had lived at Beaufort House for fifty-seven years: since 1771, when he was twelve or thirteen years old. He was registered under another name, perhaps because George and Frances didn’t want people to know of his disability. Maule used now-outdated language to refer to James, including ‘idiot’, which suggests a profound or severe learning disability. He also stated that, because of this, James was ‘incapable of managing the most ordinary affairs’.

Beaufort House

Beaufort House was established as an asylum in the 1750s under the name of St John’s Asylum for the Insane. It was located on North End Road in Fulham, west London. At that time, the area was relatively rural and known for its market gardens.

In 1831, when James was still living at the house, it had only four residents, of both sexes. It is likely that the male and female residents were strictly segregated. In 1859 Beaufort House became the headquarters of the South Middlesex Rifle Volunteers and it was demolished around 1900.

Beaufort House by illustrator Stephanie Wilson. This likeness is inspired by a photo and sketch from the book ‘Fulham Old and New’ by Charles James Feret.

Asylums in the 1700s and 1800s

In 1831 Beaufort House was one of 106 private licensed asylums in England and Wales. This had risen from just 16 in 1774.

Some proprietors took pride in the high social status of their residents. For example, the proprietor of Dunnington House in Yorkshire said, ‘I only admit a certain number of patients into my establishment and these are persons of distinction.’

Some of these houses, which charged high fees and accommodated few residents, provided them with extensive walled gardens, libraries, and games.

Humbler people with disabilities or mental illnesses were known as ‘pauper lunatics’. If they couldn’t be supported at home, it was usual for them to live in workhouses or in public asylums. These were often overcrowded.

People with disabilities of any social status, however, could be subjected to mistreatment. This could include neglect, unclean living conditions, restraint, lack of privacy, physical and sexual violence, and purposeful isolation from visiting family and friends.

Moreover, self-interested relatives could confine family members to asylums in order to take control of their estates and fortunes, in exchange for the right fee paid to the proprietors.

Disinherited

The perception that James was unable to manage his own affairs was likely the reason that his family disinherited him.

His mother’s will

Frances died in 1778, when James was around 20. Her will, written two years earlier, states:

‘I Frances Duff give and bequeath to my eldest son James Duff £100, to my eldest daughter Jane Dorothea Duff £200, to my daughter Frances Duff £200 and to my son George Duff the residue or remainder of all the real and personal estates of whatever nature or kind soever in the Island of Jamaica for my son George Duff’s sole use. My father Gibson Dalzell bequeath unto me some shares in the Sun Fire Office with the same power… I give to my son James Duff one share to my daughter Jane —- Dorothea Duff one share my daughter Frances Duff one share and to my son George Duff twelve shares for his sole use.’

James was the eldest surviving son, which would ordinarily grant him a greater share of his parents’ inheritance. However, he received the least out of his siblings in cash and in shares in the Sun Fire insurance company, which Frances had inherited from her grandfather. Lucky Hill, her Jamaican estate, went entirely to George, the dissolute and irresponsible second son.

His father’s and brother’s wills

After Frances’s death, James’s father, George, relocated to Milton Duff near Elgin and then to South College in Elgin itself. When he died in 1818, his property was also inherited by his second son, George, including South College and Bilbohall in Moray.

Young George, who died in 1828, divided his estates between various cousins. These included Bilbohall, which he gave to Alexander Francis Tayler, the husband of James and George’s cousin, Jane.

Tayler acknowledged that his inheritance was due to George’s having ‘left a brother who has been insane from early life’.

Lucky Hill wasn’t inherited by any family members. This was perhaps due to George’s own financial mismanagement. By 1790 Lucky Hill was owned by a William Dunlop, and two years later was held by mortgagees.

James Duff 2nd Earl Fife (1729-1809) was uncle to James Duff. This portrait is a copy after Francis Coates. It is cared for by Aberdeenshire Museums Service/Aberdeenshire Council and is on loan to us at Duff House.

A long life

James died at Beaufort House in 1832, aged around 74. He had outlived all his siblings and his parents.

James’s family tree.

We don’t know whether he was visited by his family there, nor do we have his own words to learn about his thoughts and experiences. However, what was written about him gives an insight into the life of a person living with a disability in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Although of high status, as the grandson, nephew, and cousin of the earls Fife, James was, from a young age, separated from the society into which he was born.

Acknowledgements

This blog draws on information found in Alistair and Henrietta Tayler, The Book of the Duffs, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1914), Anne M. Powers, ‘A Lunatic in the Family’, A Parcel of Ribbons website (2012), and the Legacies of British Slavery database.

Behind the scenes with the illustrator, Stephanie Wilson

We approached Edinburgh-based artist and illustrator, Stephanie Wilson, to help create a likeness of James. It was no easy task given the very little we know about him. Here, she reflects on the challenge of representing someone whose life we know very little about.

Stephanie says:

I feel very privileged to have had the opportunity to learn about and explore aspects of James’ life through creating this drawing.

Initially I was intrigued by the challenge of creating a drawing to capture and represent someone based upon the various facts, details and opinions others captured and recorded. Especially with some of the bias and prejudice they held.

I wondered how I could represent a likeness of James from the information gathered, whilst still being mindful that so much of him, his disability and his life was not recorded.

I responded to this challenge based upon my own personal experience. I reflected on times when I have sometimes felt limited by the opinions others have about my disability and how they may represent or allude to it.

It was important to me that parts of this image felt like they were incomplete or uncontained. The colour layers were added separately to enable them to overlap or overspill from the single line trying to contain him.

I decided to draw using one continuous line. This represented how a single line of text could reflect the potentially limiting views people of that time had about him.

I tried to show the inability to render a complete image of him by drawing multiple versions of him in different fragmented positions and at different ages. The poses include him reading because we do have evidence that was something he enjoyed.

I included period elements, like the clothes he was wearing, which are simple but of good quality to represent his wealth.

At the centre of the illustration is a drawing of Beaufort House, taken from an archive photo, to represent how much of his life was spent there.

Finally I added a yellow brush stroke to weave between the different layers of the drawing. It takes a journey through the image and his aging life, showing how these elements may intertwine and connect.