15 February 2024 will mark the 150 anniversary of the birth of the remarkable Anglo-Irish Polar Explorer, Ernest Shackleton. Shackleton’s voyages to the Antarctic are legendary, but his life away from the ice was somewhat chaotic. Here, we explore his incredible life story, from disgruntled schoolboy to Polar hero and his time in Scotland.

Origin Story

Born in 1874 in County Kildare, Ireland, Ernest Shackleton and his family moved to England when he was 10. He attended Dulwich College but hated it. He often played truant, got into fights and was given the derogatory nickname ‘Mick’ due to his Irish heritage.

The young Shackleton was a dreamer, devouring the stories of Ryder Haggard and Jules Verne, which filled him with a longing for adventure and the discovery of treasure, a desire he never outgrew. His father, Henry Shackleton, wanted his son to become a doctor, but the young Shackleton was drawn to the sea. Henry agreed his son could enrol in the Merchant Navy when he turned 16, thinking that a year of service would soon change his mind. On this agreement, Shackleton’s grades at school improved dramatically, particularly in mathematics, which would be important for navigation. However, he left school when he turned 16 without completing his final year and made his way to Liverpool.

Shackleton served his apprenticeship on the Houghton Tower, a three-masted sailing ship. The Merchant Navy apprenticeship was notoriously rough. The foul-mouthed, rough-living, hard-drinking sailors shocked the rather sheltered young man. He would escape by reading, but eventually found his place amongst his crewmates. He was a great storyteller and kept the men entertained with his tales. Contrary to his father’s expectations, the one-year apprenticeship did not put him off and he signed on for four more years.

RRS Discovery

In 1897 Shackleton met Emily Dorman, a friend of his sisters. Shackleton was captivated and determined to marry her – despite her having refused 16 other marriage proposals! To show Emily and her wealthy family that he was a good marriage prospect, he secured a position on the Royal Navy Discovery Expedition led by Robert Falcon Scott. This would be the first British exploration of the Antarctic for over sixty years.

Captain Scott led the Royal Navy Discovery Expedition which became the first British expedition to the South Pole. © Scott Polar Research Institute. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Discovery left London in July 1901 and arrived in the Antarctic in January 1902. As third officer on board the Dundee made vessel, Shackleton oversaw provisions and entertainments. Full of energy and enthusiasm, he became a popular member of the crew, speaking and mixing with both officers and men alike. Shackleton’s personality was very different from Scott’s; he was classless, and his Anglo-Irish background meant he was always somewhat outside the establishment.

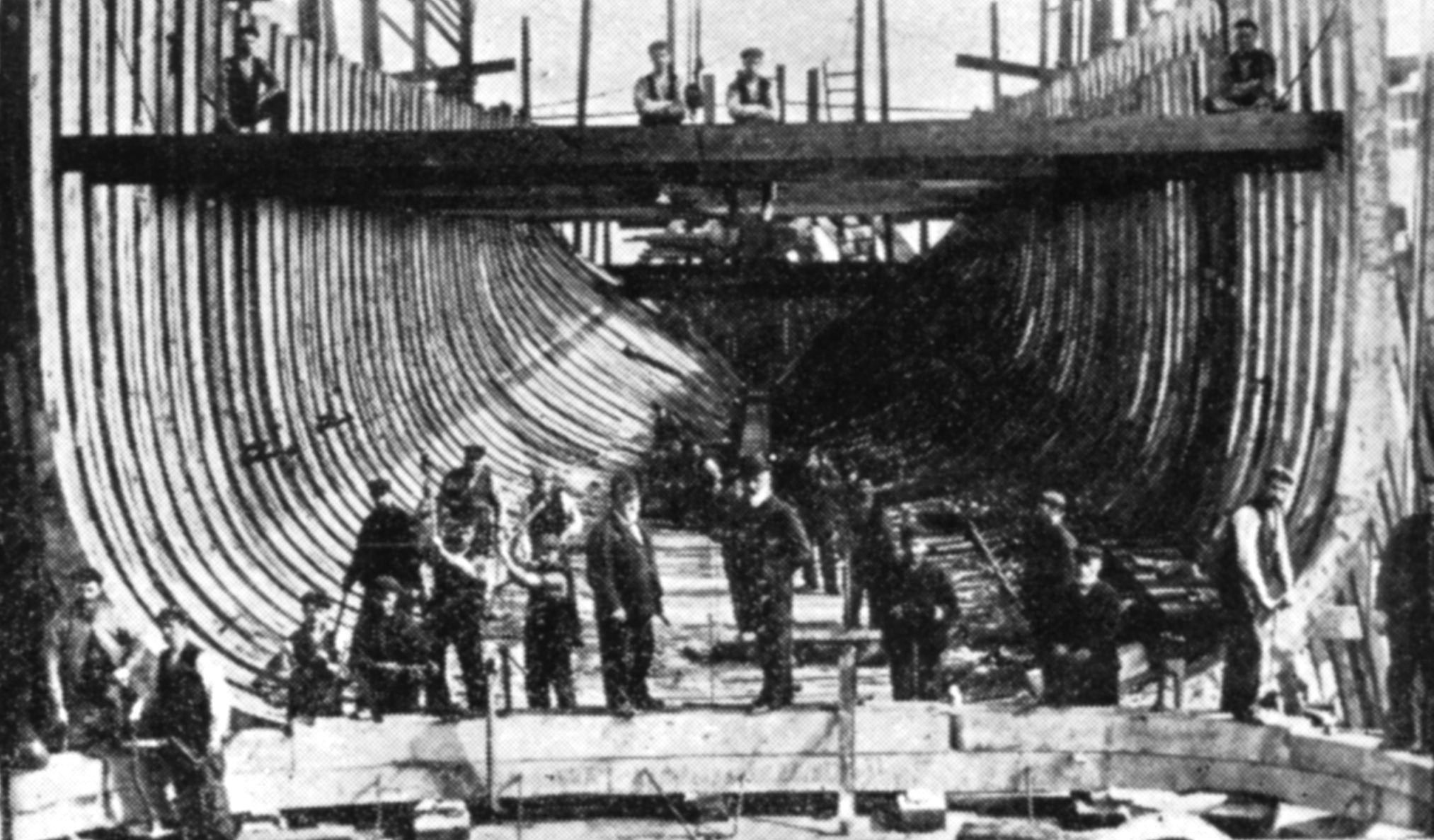

The “Discovery” was launched in Dundee on 21 March 1901. This is a picture of the framework of the vessel at the Dundee Shipbuilders Company the previous year. © Douglas MacKenzie. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

During the expedition Shackleton developed scurvy and much to his annoyance was sent home on medical grounds. He arrived in New Zealand in March 1903, before travelling onwards to reach Britain. Back home, he became the voice of the Discovery Expedition. He was a natural orator captivating crowds with his storytelling and charm. Shackleton left the Merchant Navy but was uncertain as to what to do next. He dabbled in journalism, securing a job on the “Monthly Magazine” but quickly grew bored.

Move to Scotland

In 1904 Shackleton and Emily married and moved to Scotland. He became Secretary of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society (RSGS), whose offices in those days were in what is now the National Portrait Gallery in Queen Street, and the newly married couple lived in Learmonth Gardens across the Dean Bridge.

The Scottish National Portrait Gallery was designed by Rowand Anderson for the joint use of the Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of Antiquities. It was built in 1885-90 for £50,000, a gift to the nation by J R Findlay, owner of the Scotsman newspaper. © Courtesy of HES (Francis M Chrystal Collection). Zoom in on Canmore

Shackleton arrived at the RSGS like a whirlwind. He introduced telephones – much to the consternation of the rather conservative members – wore snazzy suits, and on one occasion smashed a window by hitting a golf ball. Although he did not stay in the position long, he increased membership by 23%.

Back to the ice

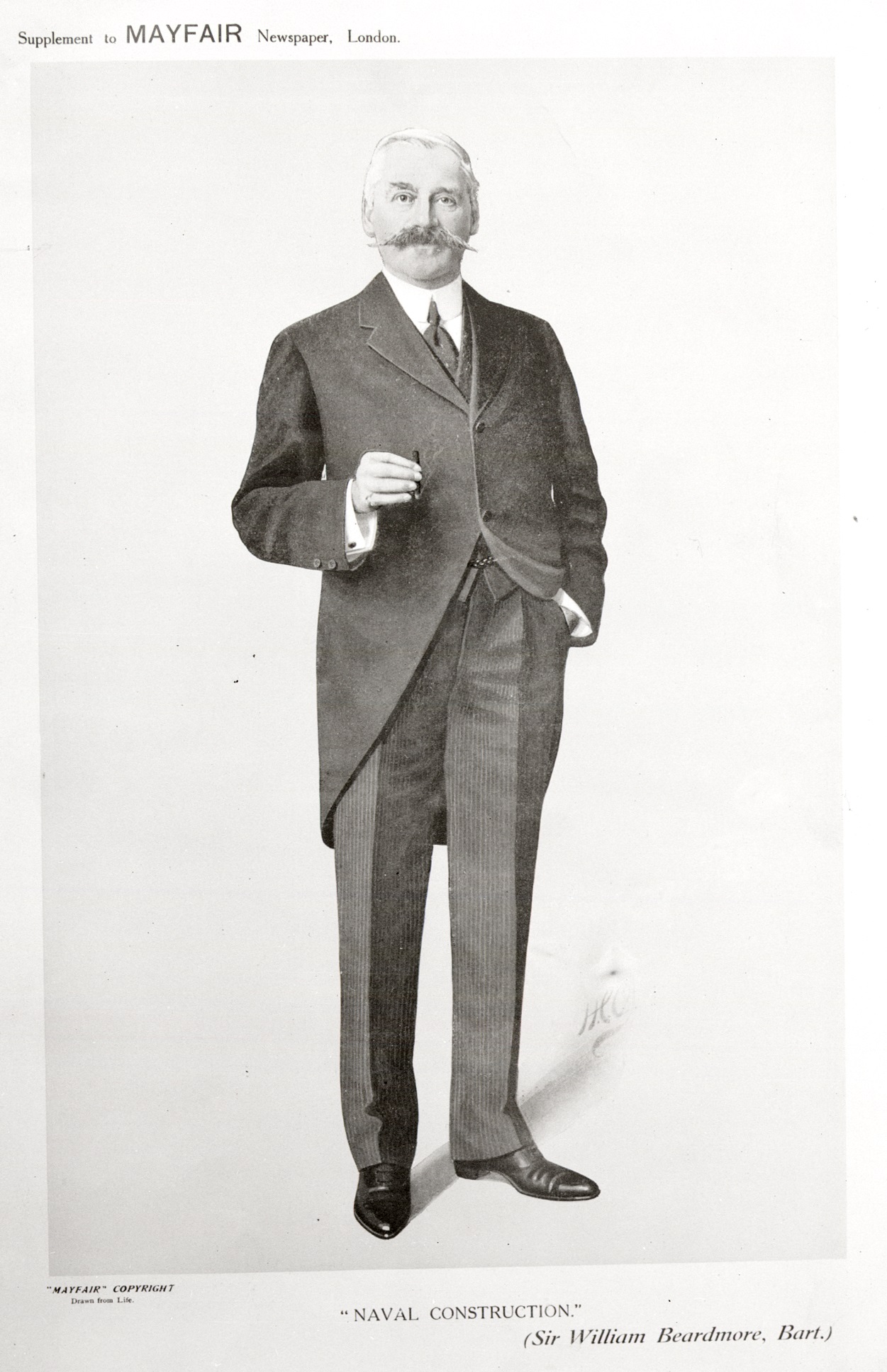

Shackleton was quickly growing bored away from the ice. He had many failed business attempts including a tobacco company and a gold mine. Shackleton even tried politics, standing as a Liberal Unionist in Dundee. He was no politician and knew nothing about politics but certainly entertained the crowds on the hustings. He came fourth out of five candidates claiming “I got all the applause they got all the votes”. After meeting the industrialist William Beardmore, who owned shipyards on the Clyde, Shackleton became an ambassador for the company. However, he was soon bored. Restless once more, and began to plan a new expedition south.

Although ostensibly an industrialist Beardmore was also known for his patronage of certain pursuits. He famously sponsored Shackleton’s 1907 Antarctic expedition. This sponsorship resulted in one of the world’s largest glaciers being named after him.© Beardmore Collection. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

The Scottish Polar explorer William Speirs Bruce had previously managed to secure private backing for his own little known, but hugely successful Scottish National Antarctic Expedition. Inspired by this, Shackleton hoped to use his considerable charm to raise the funds for his new venture from wealthy donors or lenders. He was hopeless with money. All his attempts at wheeler-dealing and get rich quick schemes ended in failure. On the rare occasions when he had cash, he would often give it to charity. Beardmore himself provided some funds for Shackleton’s new venture, although it has been suggested this may have been to put distance between Shackleton and Beardmore’s young wife, Elspeth. Shackleton loved the company of women and it seems women – young and old – loved him.

Nimrod’s journey

Having successfully raised funds, Shackleton procured the Nimrod, a three-mast sailing ship built in Dundee. His goal was to become the first person to reach the South Pole. The ship departed London in August 1907, reaching the Antarctic Circle in January 1908.

The Antarctic ice © Royal Scottish Geographical Society. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

He came within 97 miles of reaching the South Pole before he made the courageous decision to turn back, knowing that if he continued there would not be enough supplies for the men on the return journey. He later wrote to his wife Emily “I thought you’d rather have a live donkey than a dead lion”.

Shackleton had travelled further south than anyone before him. He returned a hero, was knighted, and embarked on a series of lecture tours. However, at the end of 1911 came the devastating news that the Norwegian Roald Amundsen had succeeded in becoming the first person to reach the South pole. Shackleton was one of the first to congratulate him, but both he and his Discovery colleague Scott became Britain’s tragic Polar heroes. Shackleton was by now a father of three, but he was often absent. His marriage was strained, and he was drinking heavily. All his money-making schemes had failed. The south called once more.

A tale of Endurance

His next venture, The Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition was audacious. The South Pole had already been reached. His new plan was to cross the Antarctic continent. He never achieved this, but the story of what happened is legendary. His ship the Endurance (named after his family motto, ‘by endurance we conquer’) became stuck in the ice and eventually sank. Shackleton was determined to get his men home. His optimism, drive and leadership kept up the men’s morale as they endured months of isolation and horrific conditions. They took to the lifeboats, eventually reaching Elephant Island, a place so remote there was no hope of rescue.

Leaving 22 men on the Island under the command of his number two Frank Wild, Shackleton and 5 others set off in a lifeboat (named after his largest donor, the Dundee jute merchant James Caird), enduring a perilous journey of 800 miles in the roughest seas imaginable. Thanks to the navigation skills of Frank Worsley, they managed to reach South Georgia, but they then had to embark on a 36-hour trek over the uncharted mountain range to reach the whaling station and help at last. The 28-man crew of the Endurance all survived thanks to the leadership skills, optimism, and determination of Shackleton.

This was where Sir Ernest Shackleton eventually found help after his ship ‘Endurance’ was crushed in the ice in October 1915. He led his party some 180 miles to the safety of Elephant Island. From there made an 800 mile long voyage in a lifeboat with five companions to South Georgia. © Nicol Thomson. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Final Voyage

On their return to civilization, the men were horrified to hear that the First World War, which had just begun as they embarked on their journey, was still raging. Many joined up. Shackleton himself was too old for active service. He became an army officer and was deployed to Murmansk equipping and advising on Polar gear for the North Russian Expeditionary Force who were fighting the Bolsheviks.

At the end of World War I Shackleton felt again lost and restless. He yearned for one last adventure and wanted his old pals to go with him. So, in 1921 Shackleton, Wild, Worsley, and many other Endurance survivors embarked on the Quest Expedition, financed by an old school friend. The plan was to circumnavigate and record Antarctica. Shackleton initially stayed in his cabin and was quite irritable, not like him at all. It was only when he reached South Georgia and had a night ashore with the whalers that he became the Shackleton of old. That night he returned to his cabin and died of a heart attack; he was only 47 years old.

His body was being accompanied back to Britain when a telegram was received from Emily, Shackleton’s widow, requesting he be buried in South Georgia. She knew him so well, for this really was the only place where he ever fit in.

Sir Ernest Shackleton, British explorer, died at Grytviken in South Georgia in 1922. His body was buried in a whalers’ cemetery at Grytviken; this is his gravestone. © Peter Pole. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Interested in more stories from the sea?

From the history of Henry Bell’s shipwrecked Comet, one of our more unusual designations, to the stories in the bookcases of Trinity House, there’s a lot more maritime history on our blog.

Header image: Ship model at Trinity House.

Check out more of our Collections objects from Trinity House

About the Author

Nicola Wright is a storyteller, historical interpreter, tour guide and trainer, with her colleague Lindsey Gibb she has formed the Shackleton Storytellers – Shackleton’s Orbit. For Illuminate she provides workshops, training, tours, and object handling sessions both in Trinity House and in an outreach capacity to a wide variety of groups including schools, nurseries and older peoples’ projects.

Nicola Wright is a storyteller, historical interpreter, tour guide and trainer, with her colleague Lindsey Gibb she has formed the Shackleton Storytellers – Shackleton’s Orbit. For Illuminate she provides workshops, training, tours, and object handling sessions both in Trinity House and in an outreach capacity to a wide variety of groups including schools, nurseries and older peoples’ projects.