Many of you will know Doune Castle’s connection to the hit TV show Outlander, with its story of the Jacobite hero Jamie Fraser and his adventures in the American colonies. But did you know that the truth is every bit as exciting as fiction? Meet John Witherspoon…

How it all began

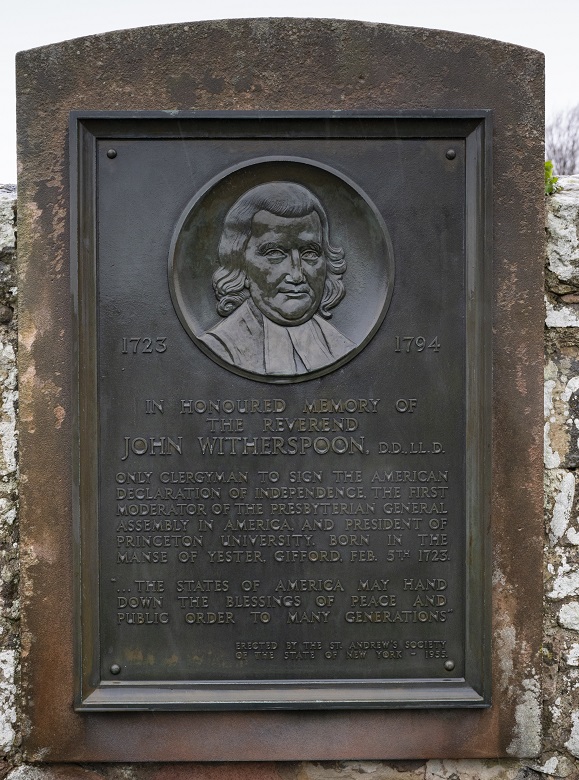

John Witherspoon was born in Gifford, East Lothian on February 5 1723. He obtained a Master of Arts from the University of Edinburgh in 1739 and continued on to study divinity. Unlike the hero of Outlander however, Witherspoon was a staunch Protestant and supporter of republicanism. Unsurprisingly, when it came to the Jacobite Uprising of 1745-46, Witherspoon was firmly on the side of the Government forces.

John Witherspoon by artist Dianne Sutherland (licensed via Scran)

On 17 January 1746, having already withdrawn from England, the Jacobite army engaged the Government army at the Battle of Falkirk. After the battle, John Witherspoon, along with several other men, found himself imprisoned in Doune Castle, where some of the Jacobite forces were garrisoned.

Accounts vary over his role in the battle. Some say that Witherspoon was present with an Edinburgh Company that he himself had raised. Others claim he was simply a bystander caught up in the Government retreat. Another account says that the actual reason he was there was ‘from curiosity to see a battle’. If that’s true, it goes to show that young men have been making foolish decisions for a very long time!

Escape from the fortress

Little is known of Witherspoon’s imprisonment in Doune Castle. Fellow inmate John Home (who also went on to later success) wrote latterly of their internment in a ‘ghastly room’ with two sub-chambers at one end which were used for sleeping. This description matches what is now called Mary Queen of Scots’ Bedchamber, near the top of the Kitchen Tower.

What apparently happened next is the stuff of action movies.

Witherspoon, together with Home and two other men, knotted sheets together to form a rope – yes, really! This they threw from the battlements and began to descend. Witherspoon and Home escaped unscathed, but one man died of his injuries after the rope broke. The fourth climbed down the wall anyway and fell 20 feet, although he only broke his ankle and several ribs.

Success at Princeton

The cast of a reenaction of John Witherspoon’s exploits held at Doune Castle back in 2015

After these two narrow escapes, one from death in battle and the other from death by falling from the walls of Doune Castle, Witherspoon served as a minister in Scotland for the next two decades.

From 1758 to 1768, he was based at the Laigh Kirk, Paisley. During this time, he met Richard Stockton, a notable American lawyer, and Benjamin Rush, a medical student from Pennsylvania. They persuaded him to emigrate and take up the position of president of the College of New Jersey.

Witherspoon assumed the presidency of the college, which later became known as Princeton University, in 1768.

During his time there, Witherspoon instituted numerous reforms, including modelling the syllabus and structure on that used at the University of Edinburgh. He introduced the school of philosophy known as Scottish common-sense realism and revised the moral philosophy curriculum, believing that moral judgement should be pursued as a science. He also firmed up entrance requirements, enabling Princeton to compete with Harvard and Yale.

Becoming a rebel

Beith, where John Witherspoon was minister from 1745 to 1758, before moving to Paisley

But this is by no means the end of Witherspoon’s story.

The man who had staunchly supported the Government forces and the British crown 30 years previously now found himself in a different position. He regarded the lack of colonial representation in the British parliament as unjust, but initially cautioned against the severance of ties with the crown as being potentially destructive. By 1775, however, Witherspoon was evolving into a fully-fledged revolutionary.

This seems to have happened for two reasons. Firstly, Witherspoon was a Presbyterian, and parliament was intent on having an Anglican Episcopacy in the colonies. This would mean an Anglican Bishop, giving the colonies even less say in their own governance, as well as curtailing the Presbyterian Church.

Secondly, Witherspoon’s change of heart was inspired by his home nation. He argued that Scotland’s union with England was not equal, and that the former had been absorbed by the latter. Witherspoon saw that this was the future for the colonies if they did not take matters into their own hands.

John Witherspoon: Founding Father

Witherspoon joined the New Jersey Committee of Correspondence and Safety in early 1774. Two years later, he was elected to the Continental Congress as part of the New Jersey delegation, where he was appointed congressional chaplain.

In 1746, Witherspoon had been imprisoned in Doune Castle for opposing a rebellion which he perceived as a threat to his religious and civil freedoms. Now, his transformation into a leading American revolutionary was founded in those same fears.

And so, in July 1776, John Witherspoon signed the Declaration of Independence, which was itself influenced by Scotland’s very own Declaration of Arbroath. In doing so, he became one of the Founding Fathers of the United States of America.

A legacy of liberty – but not for all

John Witherspoon died on 15 November 1794. He had been President of Princeton University, convening moderator of the First General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the USA, and a Founding Father.

John Adams, the 2nd President of the USA, called Witherspoon

as high a son of liberty as any man in America”

But there is another side to Witherspoon’s story that should be addressed. The Princeton and Slavery Project began in 2013. It seeks among other things to ‘engage a broad public audience in a conversation about the many issues raised by the University’s engagement with the institution of slavery.’

John Witherspoon kept slaves and lectured and voted against the abolition of slavery. He did advocate for the humane treatment of slaves in his ‘Lectures on Moral Philosophy.’ He also tutored free African men during his time at Princeton, and did not seem to see any conflict of interest in his instructions to his moral philosophy students, his relationship with these African men, and his own practice of slaveholding. By modern standards, this seems shockingly hypocritical.

It is important to remember that this “son of liberty’s” decisions enabled his family to prosper from slavery, and indeed his new nation to embrace slavery from its foundation.

You can plan a visit to Doune Castle to see John Witherspoon’s one-time prison. Other highlights include the cathedral-like Great Hall and the beautiful grounds beside the River Teith.

For another journey from East Lothian to the USA, check out the story of John Muir.