Crofting is a long standing tradition in Scotland – but what’s involved, and how can it benefit our historic environment? Find out with our quick history of crofting.

What’s a croft?

Lots of people who visit the north of Scotland assume that they know what a croft is – it’s a little house. If you read novels or newspaper articles, you’ll often come across this idea.

But the truth is that a croft is a small piece of agricultural land, a sort of micro-farm, which may, or may not, have a house on it. There’s a strict legal definition and one of the jokes that’s told about modern crofting is that a croft is a small piece of land entirely surrounded by legislation!

The remains of a croft house on the Isle of Lewis.

But that legislation and the regulations that go with it, have preserved a distinctive, rich, communal way of life that contributes hugely to Scottish culture and helps preserve the valuable historic landscape in which it is located.

Crofts were originally, and still mostly are, tenancies. A crofter pays rent to a landlord but they can’t be put out of their land as long as they’re working it, and they can pass their tenancy to someone in their family. Most crofts are in the Crofting Counties, the areas of the former counties of Argyll, Caithness, Inverness, Ross & Cromarty, Sutherland, Orkney and Shetland, in the north of Scotland.

Crofts are grouped together into ‘townships’, where each crofter has a small area of their own and also has a share in common lands around the township that they can use for grazing livestock or for other communal activities.

How did crofts come about?

The Blackhouse at Arnol, Lewis. Once the home of a Hebridean crofting family and their animals, it’s now preserved as a Historic Scotland visitor attraction.

In the 1700s, there was a wide variety of different types of land holdings in the north of Scotland.

Big estates were owned by landowners, some of whom were also clan chiefs. Many of these estates were divided up into smaller parcels, held by a middle class of ‘tacksmen’ who paid rent to the landowners and had further tenants who paid them rent.

Some of the communities, perhaps most of them, had a social contract with their tacksmen and landowners. They understood they were related to each other, that they had a right to their land, and that tenants would carry out military service and provide rent in kind (animals, food, cloth, leather) rather than in cash.

Changing Times

The 1700s saw ideas of agricultural improvement spread through the Highlands.

There was a lot of social and political change, particularly following the Battle of Culloden in 1745 when many big estates were taken over from Jacobite landowners by the government.

It became socially important for landowners to make as much money as possible from their estates. Bit by bit, the middle class of tacksmen were squeezed out.

Cleared Township at Auliston. It was occupied by 1755 and cleared around 1855.

A lot of them emigrated to the Americas and Australia, sometimes taking all their sub-tenants with them. Increasingly landowners required rent to be paid in cash, directly to them and they started to reorganise their land in ways that they thought would bring the most income. People were moved and big farms created, sheep were introduced, planned fishing and agricultural villages were built.

Challenges

In the 1850s, potato blight struck the Highlands and Islands. Many people were very dependent upon growing potatoes for food, but now they had to buy it. They used their cash for food, not rent, and got into debt to landowners.

More and more people were evicted from their homes. In some cases they were forcibly deported out of the country, particularly to North America. This was all reported by the newspapers of the time, so it was widely known in Britain and abroad.

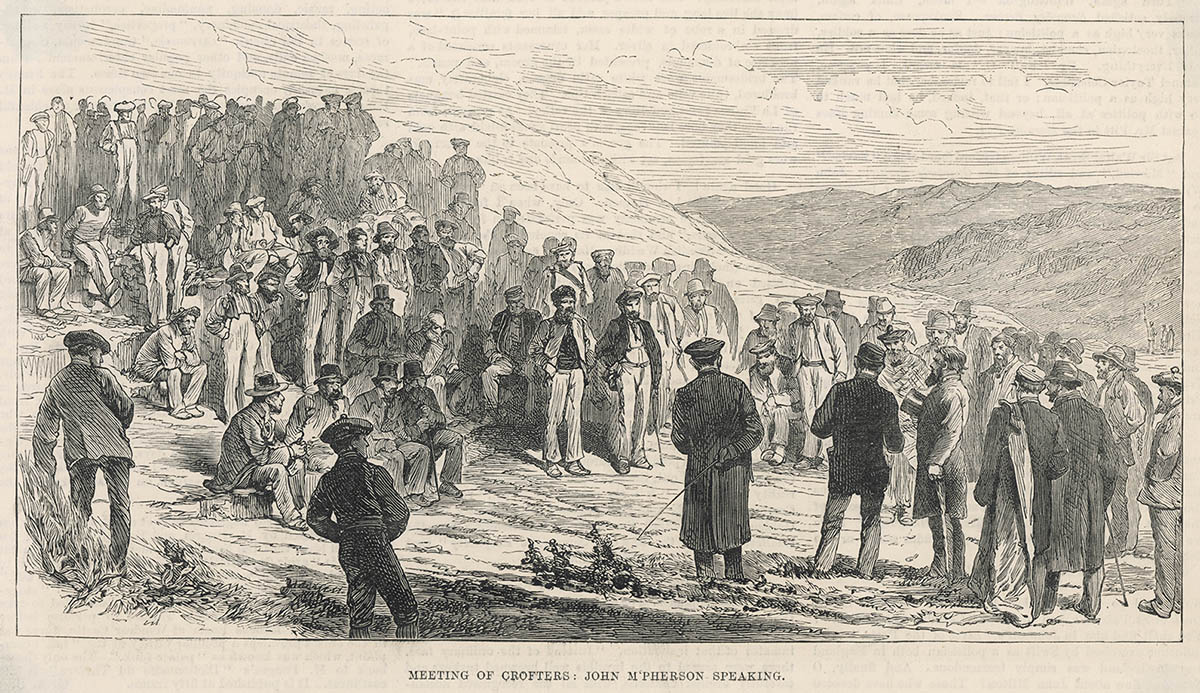

A meeting of the Skye crofters association. John McPherson speaking. © Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans

The next 30 years saw a lot of civil unrest in the Highlands and Islands. There were no controls on landowners, who could evict their tenants whenever they wanted, remove land from them, or increase rents without warning. People had no security in their homes and most couldn’t plan for the future or make improvements to their situation.

There was so much unrest and disorder it came to be called the Crofters War.

Napier Commission 1883

In 1883, the government set up a commission to investigate the conditions of crofters and cottars in northern Scotland. It was run by a diplomat, Lord Napier, and the evidence was published. You can find it at Research Alliances – The Napier Commission.

Francis Napier, 10th Baron Napier and 1st Baron Ettrick, Diplomat and Governor of Madras – by George Frederic Watts. Held by National Galleries of Scotland

These are amazing documents. You can hear the voices of the people the local communities chose to speak for them.

The very first person to give evidence was afraid to speak out until he’d been promised that he wouldn’t be evicted from his house for speaking in public, which tells you a lot about the circumstances. All these people tell us that, above all else, what they wanted was security – security of tenure to plan, to improve, to raise families, to make the best of their lives.

Crofters Holdings (Scotland) Act 1886

The result of the Commission was the Crofters Holdings Act, passed on 25 June 1886. Its main outcome answered that main demand for security of tenure.

It created legal definitions for:

- who was a crofter

- which areas were crofting parishes

- what a crofting township was and how it should work

It provided legal protections for all of these, particularly by creating the Crofters Commission. This was a land court to help decide disputes between landlords and tenants.

Crofts were designed to provide subsistence and a bit of income for people who would make their cash income from other activities – weaving, fishing, shoe making, being the postie – all the things that are needed for a community. The law provided protection and structure for a system that was similar to the traditional, partly communal, subsistence farming that had existed for hundreds of years. It preserved that way of life, that had disappeared or was disappearing elsewhere in the British Isles.

Inside The Blackhouse at Arnol, Lewis.

There still weren’t enough crofts for everyone who wanted them, and as society has changed there have been numerous Acts of Parliament since that time to create more crofts, address issues and change regulations around the details of crofting life. The basic structure of how crofting works, though, was set up in the first Act. It still works that way.

Crofting Today

Crofting still exists – crofters live on the land and still run their crofts. For a while, in my childhood, it was mostly livestock and particularly sheep on the crofts. Nowadays, you see more and more horticulture as polytunnels and polycrubs are more widely available.

Crofters may be doctors, teachers, bus drivers, nurses, weavers or, indeed, archaeologists. Crofting has kept rural communities on the marginal agricultural land of northern Scotland, managing its fragile ecology, farming in a low-intensity system that protects the historic and natural environment of the area.

The Crofters Holdings Act created a legal framework in which an age-old system of subsistence and small-scale farming could survive in the modern world.

It shows us different ways of managing land for the benefit of the environment and the community.

Crofting is one of the last surviving remains in the British Isles of that peasant subsistence farming. It’s associated communal structure, and its culture, practices and approaches to life and land management have the potential to provide us with guidelines for a more sustainable future for Scotland.

Delve deeper into crofting – and more!

Want to learn more about croft houses, or other types of historic building? The Engine Shed, our building conservation centre, is the place to go!

For instance, you can find out how techniques used in past can help us build sustainably today. Alternatively, see how historic homes can be made energy efficient.

For more big stories from little buildings, check out our history of small getaways.