Greengate Close in Kirkcudbright is a row of small cottages, linked by a cobbled path and a garden enclosed by trees. In the early 20th century this lane in rural Scotland became a place where women could work, live, and create together.

In the autumn of 1918, four of these visitors memorialised their relationship in the form of a fairy-tale. Their work captures a sense of Greengate as a site of creativity.

King arrives in Kirkcudbright

Greengate Close was created by the artist and designer Jessie M King. In defiance of her family’s wishes King built a career in the arts, studying and later teaching at Glasgow School of Art.

New Kilpatrick Church, where Jessie’s father was the minister. © Crown Copyright: HES

Her elongated figures and organic lines showed her allegiance to what would later become known as the Glasgow Style. Her work later became bolder reflecting the vibrant modernist designs she encountered in Paris.

King’s early and international success as an illustrator gave her the funds to buy 44 High Street in Kirkcudbright in 1908. The artist moved in with her fiancé, designer E. A. Taylor, and began renovating the cottages and garden behind her house.

King’s late 18th century terraced house on the Kirkcudbright High Street is now category B listed. Image courtesy of Keava McMillan.

The couple were first drawn to the area by Kirkcudbright-born Glasgow Boy E. A. Hornel who lived in the formidable Broughton House. The home King set up would be very different.

A bright splash of creativity

Long before Kirkcudbright’s high street houses were painted in beautiful colours, the Taylors painted the gates to their own house and to the Close behind their house an emerald green. This slash of colour became a symbol of their home and their community. King incorporated the gate into her own signature. It appears alongside her initials and a sketch of a rabbit on her letters and designs.

Jessie M King at the gate of Greengate Close in 1949. An example of her signature is shown below. © Glasgow Museums. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Greengate became known as a hub of creativity for emerging artists and students. It also became a resource for the local community. Jessie M King organised pageants from 1917 to raise money for the Scottish Women’s Hospitals. Greengate artists continued to create work for celebrations, shows, and local children.

King was known for her illustrations of otherworldly figures from myths, legends, and folktales. Kirkcudbright residents remember her as a figure with eccentric, bordering-on-magical qualities. These included a fairy circle in the Greengate garden, the ability to see auras, and friendships with rabbits. She bicycled around the town wearing buckled shoes, a long black skirt and cape, topped off with a wide-brimmed black Breton hat.

The artists

King and her husband moved to Greengate permanently during the war in 1915. They relocated their sketching schools in Paris and Arran to the small town. The cottages in Greengate were rented out as studios for young artists.

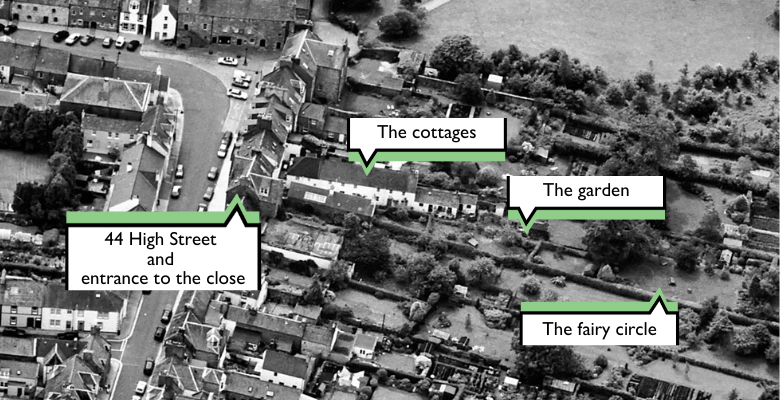

Aerial photo showing the layout of the cottages and gardens. Zoom in for a closer look on Canmore. © Crown Copyright: HES

Behind each of the brightly coloured doors lived groups of creatives and visitors from the art colleges in Edinburgh and Glasgow. The rent was cheap, breaking down financial barriers to joining the community. One student, William Miles Johnston, could not afford the train fare and cycled from Edinburgh to Kirkcudbright to spend the summers there.

The category B listed cottages at Greengate. There are three cottages on the south side and two on the north side. Image courtesy of Keava McMillan.

Inhabitants lived and worked alongside each other in this bohemian environment. King’s sketchbooks give a sense of how much time she spent outside with her students, drawing the gardens and coastline. They shared meals and held costume parties. The turnover of visitors and close living arrangements at Greengate provided a constant stream of new techniques and ideas. These networks provided an essential source of support during a devastating world war that saw many artists enlisted and restricted the international travel and exchange which had sustained Scotland’s creative circles.

King and her husband worked on everything from illustration and painting to ceramics and furniture design. Greengate welcomed artists, many of them women, who worked with diverse materials. The Close became known for its women artists, with the press describing them as a coterie.

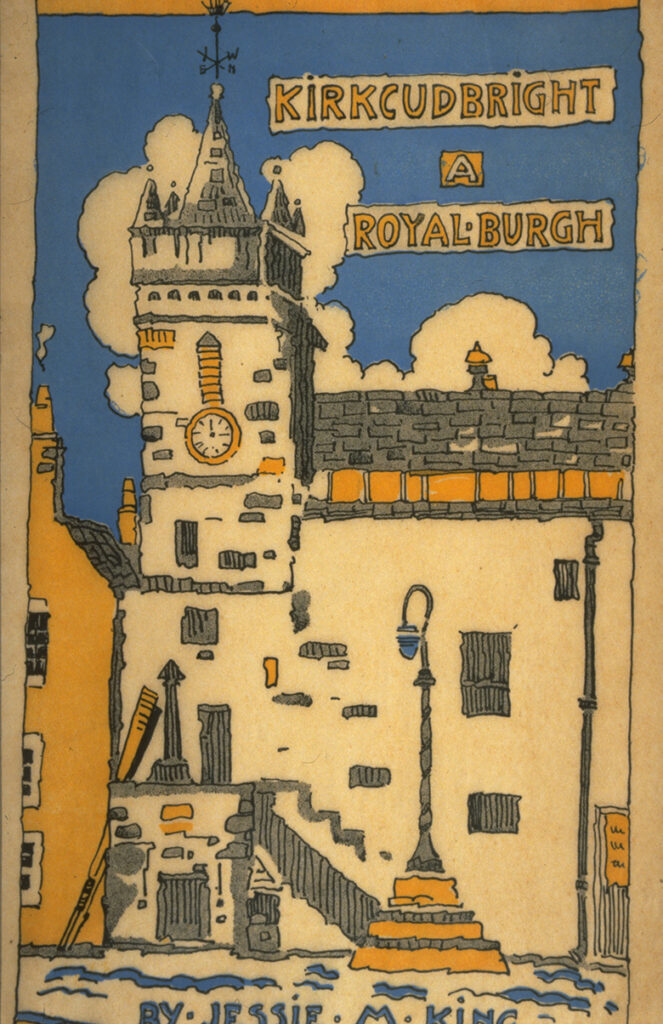

This 1934 booklet was written and illustrated by King. It includes 17 illustrations of Kirkcudbright. © Dumfries and Galloway Council. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Queer Greengate

King’s openness and imagination created a unique space with a bohemian reputation that allowed queerness to flourish under the cloak of artistic eccentricity.

The residents of Greengate Close around 1925. From left to right are Isobel Hotchkis, Anna Hotchkis, W Miles Johnstone, Agnes Harvey, Dorothy Johnstone, Dorothy Nesbit, Ada King and Jessie M King. © Dumfries and Galloway Council Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

The writer Dorothy L. Sayers, whose smoking and masculine straight skirt raised eyebrows of their own in Kirkcudbright, set her mystery novel Five Red Herrings in Greengate Close. Two of her characters are a pair of women artists who live in adjacent cottages and appear as a unit.

There were queer women living and working at Greengate in the interwar period when lesbians were being vilified in the press and considered for criminalisation in parliament.

The artist Anna Hotchkis could openly desire King when she visited the Close as a student and still return to live permanently in the Close as her neighbour later in her life.

Greengate style

At a time when the popular press stoked concerns that women wearing trousers in public would lead to the downfall of society, Greengate was isolated enough to let women resist restrictive expectations. Artists like Cecile Walton donned fashionable loose trousers to work in, suffragette Vera Jack Holme lectured in her driver’s uniform, and Dorothy Nesbit explored the countryside on a motorbike which frequently had to be fixed by Holme.

King herself adopted the masculine nickname Jake and worked as a designer for Liberty, a company which specialised in “reform dress”. This Victorian fashion trend gave women greater freedom of movement in their clothing.

Rural Dumfries and Galloway was far from a queer utopia. When Walton moved back to Kirkcudbright in the 1940’s she had to give up her ties and trousers. If she wanted to be welcomed into the community as an older woman, she had to relinquish the styles of dress she had access to as a younger woman as part of the Greengate group.

Vera Jack Holme

A regular visitor to Greengate Close in 1918-19 was Vera Holme. She was known as Jack to friends though not in her public life. Holme was a militant suffragette who had worked as a performer, chauffeur for the Women’s Social and Political Union, and transport driver for Elsie Inglis’ Scottish Women’s Hospitals.

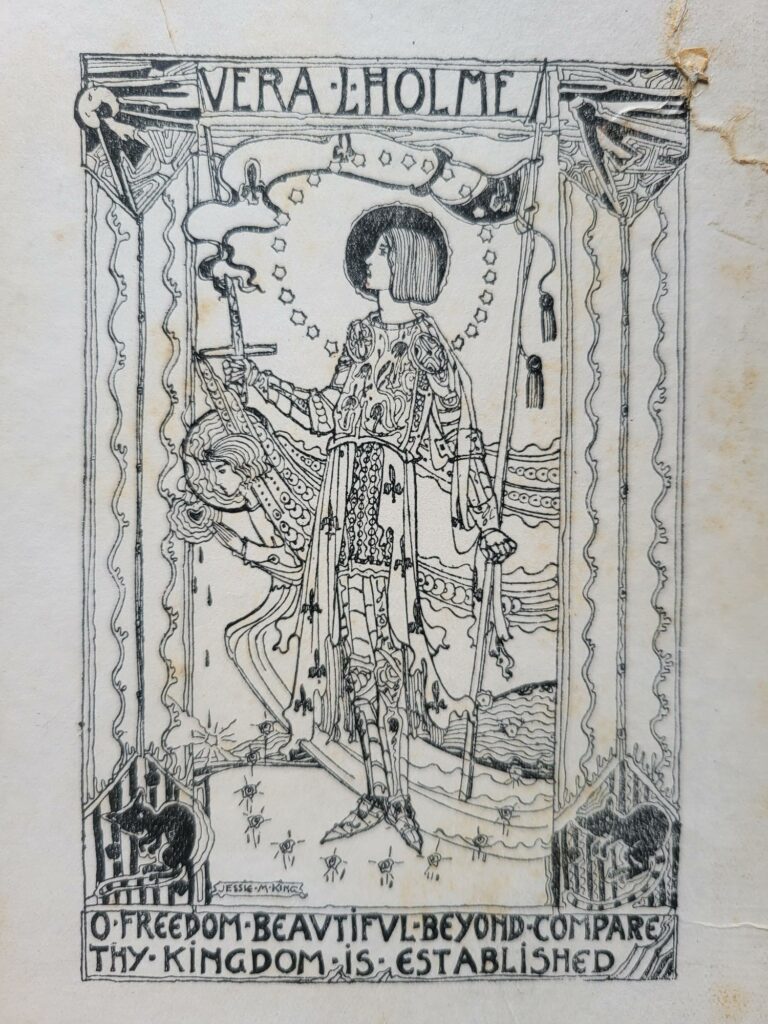

King described Holme’s company as “like a strange refreshing breeze” and the two became friends. Jessie was certainly aware of Holme’s sexuality, asking after her partners in letters. King also designed a bookplate for Holme featuring suffragette icon Joan of Arc and a quote by gay rights campaigner Edward Carpenter.

The book plate designed for Holme by King. Image courtesy of Keava McMillan.

The Fairy Family

We can get a glimpse of queer life in Greengate Close through Holme’s relationship with Dorothy Johnstone, a talented artist and tutor at Edinburgh College of Art.

Vera Jack Holme sitting and Dorothy Johnstone standing, 1918. Original held at The Women’s Library at the London School of Economics.

They stayed at Greengate with a group which included Cecile Walton and an art student, Anne Finlay. The group wrote and illustrated The Story of A Fairy Family, an enigmatic fairy story about a family of fantasy creatures.

The book narrates the relationship between the authors, borrowing their nicknames and fragments from their lives and reimagining them. Like Jessie M King’s books for children, they use the fairy story as a vehicle to explore reality.

Fairy Family is set in a land of forests, pools, and fields. The central couple of Johnstone and Holme (the Dodo and the Foozack) live in a small hut together. Like many fairy stories, the couple feel incomplete without a child. Their wish is granted through magical intervention and Spook (Finlay) appears before them surrounded by glowworms. Luckily for Spook, the Dodo and the Foozack are delighted, and the fairy family is formed. They bathe, lie on the moss, and eat toast by the fire in a leisurely life. The tale echoes details of the group’s life in Kirkcudbright found in Holme’s diaries.

Their little hut is haunted by an enigmatic character. The Ghost, Cecile Walton, wishes the family well but is not part of it. Walton was an exceptionally gifted painter and a young mother raising a toddler while her husband, the artist Eric Robertson, worked in the war. Before their marriage, Walton and Robertson had previously been in a relationship with Johnstone.

Found families

This fairy story from 1918 is queer not just because it records the love between two women or features the ex-partner of one of them. By showing Spook’s discovery of her new parents it shows the idea of a found family – a family that is chosen rather than given.

This does not always mean that the original family is replaced. For example, Holme was close to her brother who named both his children (Vera and Jack) after her. However, it shows that people created their own families outside of the acceptable confines of marriage.

Alternative living arrangements were familiar to the four authors. Walton attended the salons of Marc-André Raffalovich and Canon John Gray in Edinburgh. Holme’s close friend Edith Craig had a triangular family of her own with her partners Christopher St John and Tony Atwood at Smallhythe Place in Kent.

Missing copies?

The Story of A Fairy Family was written by hand and illustrated by Walton. One copy (now in a private collection) was kept by Holme. In a new biography of Holme released earlier this year it was revealed that Johnstone had another copy.

Walton drew four illustrations for the project so there may have been more copies made. Perhaps one for each member of the fairy family? At least two of these books were kept by the authors until their deaths. Their relationship and their time at Greengate might have been fleeting, but it was meaningful.

After Greengate

Greengate Close remained the centre of the artist’s colony in Kirkcudbright long after the fairy family moved on.

Holme moved to Serbia to continue working with her partner Evelina Haverfield. Although they continued to correspond, by the end of 1919, letters between Holme and Johnstone petered out.

After the war, Walton and Johnstone were at the peak of their careers. They exhibited with the re-formed Edinburgh Group and in a joint show.

Finlay moved to work and adventure in London, occasionally joined by Holme.

When, in 1923, Holme returned to Scotland for a place to settle down and set up home with her two new partners, she went straight to Greengate. While her new family eventually ended up in Lochearnhead, Greengate still held the memory and possibility of queer family and creativity.

Find out more

If you’ve enjoyed reading this blog, here are my recommendations for finding out more about the people and places I’ve mentioned:

- Read more about Vera Jack Holme on the LSE blog.

- Wendy Moore’s new book, Jack and Eve is a wonderful read.

- Visit Greengate Close.

- Explore the work of Greengate artists on Art UK.

About the author

Keava McMillan is an art historian, Teaching Fellow at Edinburgh College of Art, and Project Coordinator at Lavender Menace Archive. She received her PhD from the University of Aberdeen and works on interwar history and visual culture. She presented this research at public seminars at Edinburgh College of Art and V&A Dundee in 2022-2023 and is grateful for the insights from her in person and online audiences.

Keava McMillan is an art historian, Teaching Fellow at Edinburgh College of Art, and Project Coordinator at Lavender Menace Archive. She received her PhD from the University of Aberdeen and works on interwar history and visual culture. She presented this research at public seminars at Edinburgh College of Art and V&A Dundee in 2022-2023 and is grateful for the insights from her in person and online audiences.

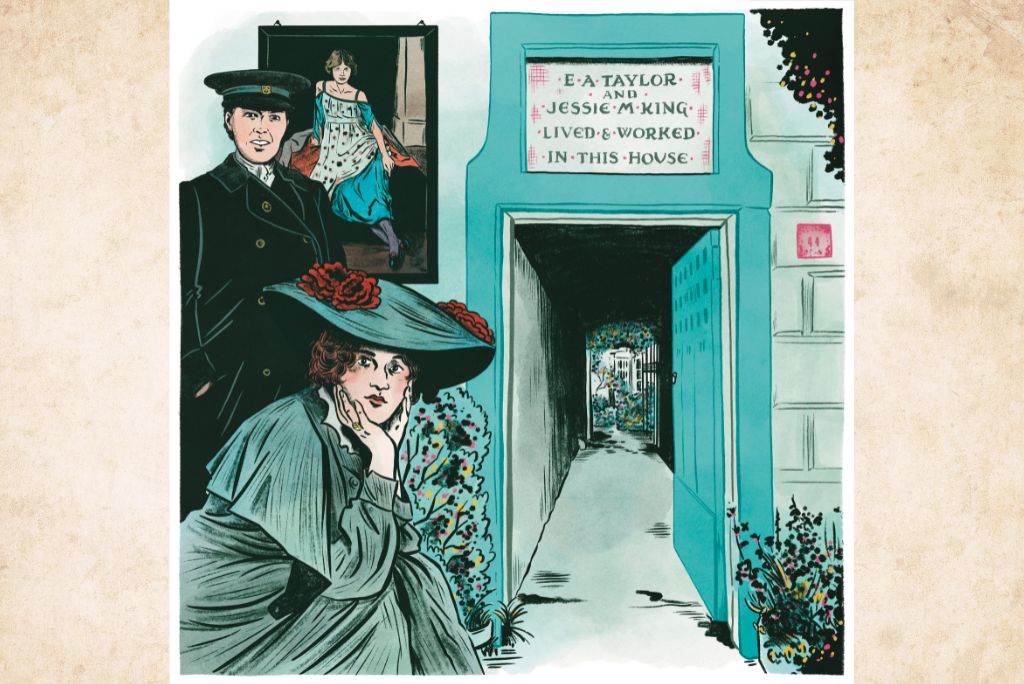

Banner image

The featured image is an illustration by Jules Scheele and includes portraits of Jessie M King and Vera Jack Holme. A copy of portrait of Anne Finlay by Dorothy Johnstone hangs in the background.