We use mathematics in our day to day lives without really knowing it. From shopping to timekeeping, we use numbers, angles, and measurements to make our lives easier. In celebration of Maths Week Scotland, let’s step back in time and round up some of the ways maths has been used in our collections over the centuries…

Going in circles

Carving architectural features onto the stonework at our properties in care requires a great amount of detail and precision. The underside of this column base from St Andrews Cathedral gives us a rare insight into how stonemasons would calculate angles for intricate carvings in the 13th century.

This flat surface essentially acted as a sketchbook for masons to create their design and an accurate template to work from. Using compasses to inscribe circles and arcs would ensure the design was both aesthetically pleasing and geometrically precise. It shows the workings for the final design of this base, as well as a plan of walls with attached columns. An experienced stonemason would have been responsible for the template and would have had a sound knowledge of geometric principles to make sure the design was exact.

Sitting on the upper surface of this stone are three secondary column bases – two are quatrefoil (four-leafed) and the third is trefoil (three-leafed). They are small in size and it’s likely that this was intended for an arcade or screen. The marks that we see on the underside show the exact dimensions of the final secondary bases, which provides a rare example of both a planned and executed design.

Keeping score

As well as being a way to pass the time, many board games involve an element of probability and strategy to win. We have examples of early versions of noughts and crosses and the 19th century shove ha’penny game in our collection.

This gaming board from Arbroath Abbey has scored lines for playing a game of ‘Merelles’ or ‘Nine Men’s Morris’.

This two player strategy game has existed for centuries, with examples from ancient Rome as well as boards like this one from some of our medieval sites. Each player has nine gaming pieces and the aim is to form rows of three counters, known as a ‘mill’, whilst removing your opponent’s counters from the board. You’d need a logical mind to decide on your strategy for winning the game.

Why not have a go at playing yourself? Download a printable board and instructions for Merelles.

Money matters

Got any loose change? We have lots of coins in our collection, from Roman currency to an Elizabeth II threepence, and everything in between!

To store these coins, you might use a ‘pirlie pig’, an earlier form of the modern ‘piggy bank’ coming from the Scots word for an earthenware vessel.

This example is from Melrose Abbey and has a horizontal slit for slotting coins into. Scottish pirlie pigs typically had a horizontal opening, whereas examples from England had a vertical slit. This example dates to the 15th/16th centuries and was made locally. Pirlie pigs were common in Scotland around this time, although not many survive in this condition because they would be smashed into pieces when full to gather your precious pennies!

A balancing act

Before the days of supermarkets and pre-packaged goods, you’d rely on scales for weighing out what you needed at market. Small pans, like this example from Caerlaverock Castle, were suspended from chains and attached to a balance arm.

They were used by merchants to precisely weigh items in small quantities, like spices, medicines, or tea. This was especially important for apothecaries when administering medicine, to ensure that the patient was given the correct dosage. You would place weights on one of the pans that you knew the heaviness of, then add the quantity of what you were measuring onto the other pan until the two balance. If the pans are not the same level then you’ve either got too much or too little product! Customers would pay close attention to this too to ensure they weren’t being short changed when doing their shopping.

Lost at sea

Setting out to sea can be very dangerous, and strong navigational skills are needed to make sure you don’t end up stranded in the middle of the ocean! Before the days of modern GPS devices, seafarers would use instruments like this octant from Trinity House to work out where they were.

By adjusting the octant to line up with the horizon and consulting your mariner’s almanac, you could then work out the latitude of your ship. This depended on measuring the altitude of the sun, and the further from the equator you were, the lower the sun would appear in the sky. It could also be used at night using a prominent star for reference instead. The octant was accurate to within one mile, so making sure that your angles were correct would be key to getting to your destination without trouble. Would you trust your navigational skills to get you back to shore safely?

Seamless recreations

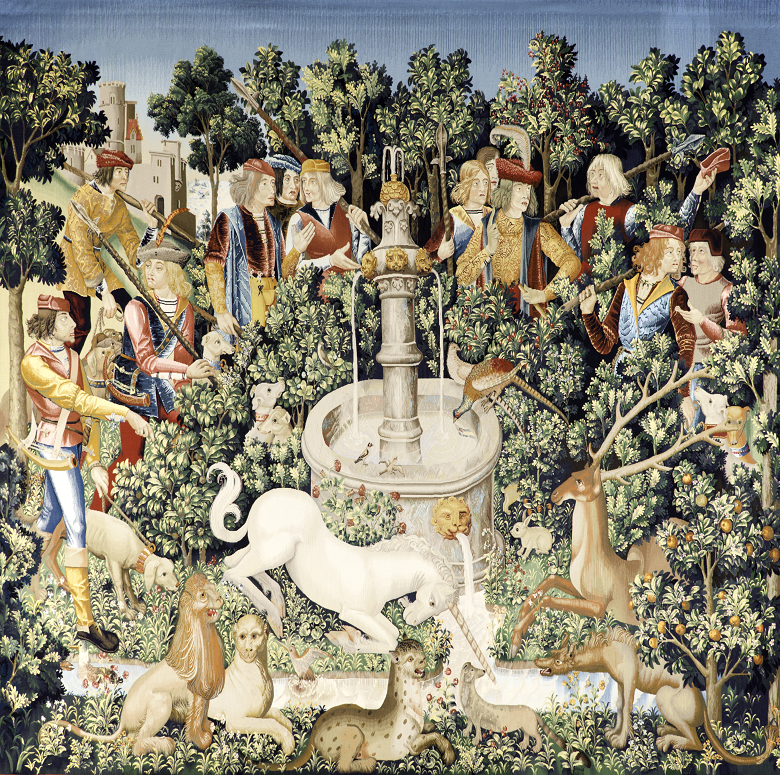

Working with textiles can often be a relaxing way to unwind, with knitting and weaving being popular past times. However, these hobbies require a keen eye for numbers, especially when following a pattern. The 18 weavers who recreated the lost tapestries of James V which now hang in Stirling Castle know all about that!

The project, which took 14 years to complete, involved calculating the amount of yarn needed to create the 7 tapestries as well as organising their time efficiently to finish the project. They wove 4 warps per centimetre (the vertical thread held in tension which yarn is then horizontally woven through) and on average completed 10 centimetres of the tapestries each week for 14 years. The original tapestries worked to 8 warps per centimetre, and there were over 100 of them, so can you imagine how long it would have taken and how many weavers you’d need to complete these!

Harping on

Music is surprisingly rooted in mathematics. Aside from timekeeping being important when writing and playing a tune, did you know that the shape of an instrument, as well as the position of holes or strings, can affect how it sounds?

The clarsach, Scotland’s oldest national instrument, was a key staple in Gaelic court music until the invention of the bagpipe in the 15th century.

This reproduction of the Queen Mary Harp is on display at Urquhart Castle and gives us an insight into the mechanisms behind creating sound in instruments. The length of strings on a harp, as well as its tension and diameter, all have a direct relationship with the sound of the string when played. The lower the note, the longer and thicker the string is. The distinctive curved neck of a harp also influences the acoustics of the instrument, and is carefully calculated in relation to the size and shape of the sound box and body of the harp. To ensure the instrument continued to play as intended, a tuning peg would adjust the tension of the strings so they would play the correct notes.