The Scottish Borders have had a long-lasting impact on the world of the gothic horror story, although most people might not realise it.

New Slains Castle and the rugged coastline around Cruden Bay in Aberdeenshire are lauded as inspirations for Dracula. But Bram Stoker’s novel also has Scottish roots further south, thanks to the Borders-born writer, Emily Gerard.

Who was Emily Gerard?

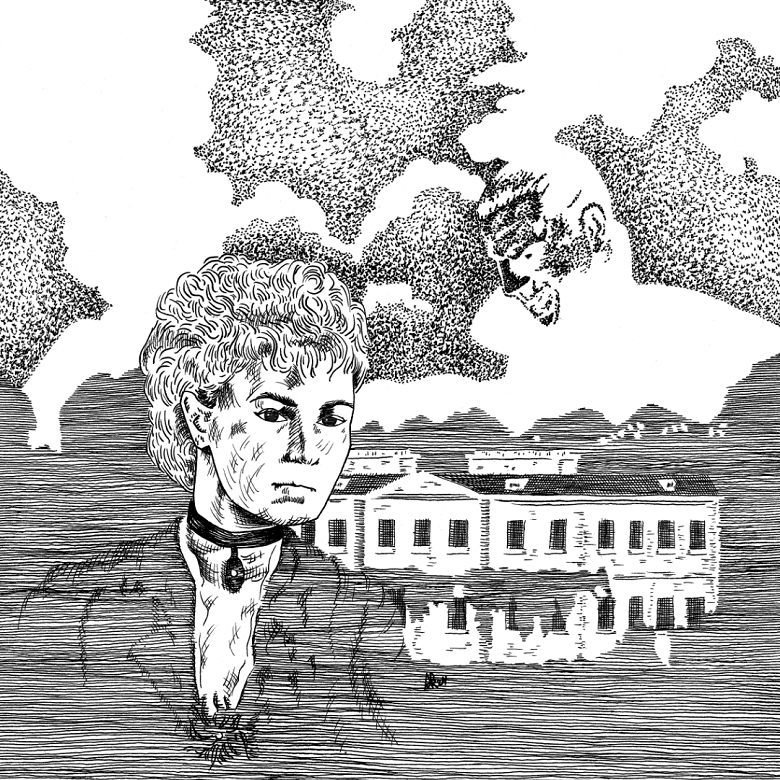

Chesters House in 1946. You can see more images of the estate on Canmore.

Emily Gerard was a 19th-century author from Chesters, near Jedburgh. During her lifetime she was regarded as an excellent travel writer with a huge understanding of European countries and language. However, this was not her whole story.

Born in 1849, Emily was the eldest of seven children. It seemed that writing ran in the family. Her younger sister, Dorothea, was also a talented novelist. Her maternal grandfather was the prolific writer and inventor Sir John Robison, and other ancestors were noted philosophical or theological authors.

Census records tell us that in 1861 the Gerards were residing at Rochsoles House in Lanarkshire. Two years later, they left Scotland for Austria.

Influenced by Europe

A linework illustration by Allan MacRitchie

Emily was well educated, having been home-schooled before studying European languages at the convent of the Sacré Couer in Riedenburg, Austria. When she began writing for the Edinburgh-based Blackwood’s Magazine, she also reviewed French and German literature. Much of her writing would feature European characters and settings.

Her first serious work was a joint effort with Dorothea published in Blackwood’s in 1879 under the pen name E.D. Gerard. It was tale of a Mexican girl adjusting to a life in Europe. Three further collaborations were also printed in Blackwood’s before Dorothea married and moved away.

A Foreigner (1896) features a cross-cultural relationship which may well have been inspired by Gerard’s own marriage to Chevalier Miecislas de Laszowski, an Austrian army officer with family roots in the Polish nobility.

The marriage, which took place in October 1869, also led to her writing taking an interesting turn that still resonates in the world of contemporary gothic horror writing today.

Travels to Transylvania

A painting from 1857 showing Hermannstadt (Sibiu) as Emily Gerard might have known it. (Johann Böbel, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Gerard’s husband’s service in the Austro-Hungarian Army meant that she was obliged to travel across the Empire, depending on the location of his postings. She bemoaned “the unaccountable decisions of a short-sighted Ministry” which resulted in “unfortunate military families rolling about the empire like gigantic foot-balls”.

Of the constant moving Gerard wrote:

Only those who have lived in this country, and tasted of the bitter-sweets of Austrian military life, can tell how formidable it is to be forced to pack up everything—literally everything, from your stoutest kitchen-chairs to your daintiest egg-shell china—half a dozen times during an equal number of years.”

But she recognised the opportunity to explore new parts of Europe and find inspiration for her writing:

I had little objection to being treated in this sportive fashion, as long as it gave me the opportunity of seeing fresh scenes and different types of people. There are two sides to every question, a silver—or at least a tin-foil—lining to every leaden cloud, and it is surely wiser to regard one’s self as a tourist than as an exile?

Gerard welcomed postings to Kronstadt and Hermannstadt (now Brașov and Sibiu, Romania). They gave her the opportunity to visit Transylvania, a region she called “the land beyond the forest”.

Emily Gerard and the origins of Dracula

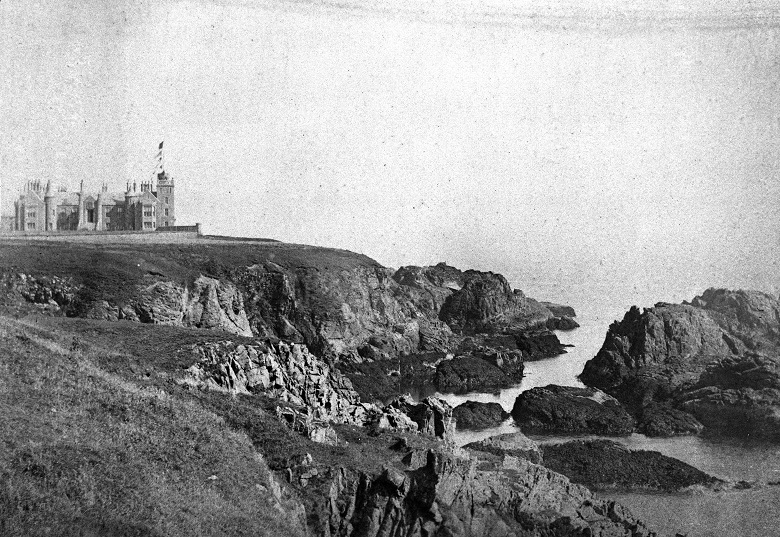

New Slains Castle is credited with inspiring Bram Stoker’s ‘Dracula’. But Emily Gerard’s writing about Transylvanian folklore also played a crucial role! (© Courtesy of HES).

Emily immersed herself in the culture and landscape of Transylvania, developing a deep understanding of Transylvanian folklore.

Her essay, Transylvanian Superstitions (1885), and book, The Land Beyond the Forest, Facts, Figures and Fancies from Transylvania (1890), are credited with giving Bram Stoker the inspiration to write Dracula (1897).

Stoker picked up the term Nosferatu from Gerard, who described the Nosferatu (or vampire) as an evil that every Romanian peasant believed in. She discusses in great depth the Romanian old woman in every village who was well versed in the methods of protecting against and dispatching a vampire, should one ever happen to appear locally:

The means by which she endeavors to counteract any vampire-like instincts which may be lurking are various. Sometimes she drives a nail through the forehead of the deceased, or else rubs the body with the fat of a pig which has been killed on the Feast of St. Ignatius, five days before Christmas. It is also very usual to lay the thorny branch of a wild-rose bush across the body to prevent it leaving the coffin.”

Other passages will be so familiar to readers of Dracula, including an almost identical description of how the villagers become suspicious of the possible presence of a vampire amongst them.

Far-reaching folklore

Emily Gerard died and was buried in Vienna in January 1905. Her obituaries in The Times and The Athenæum were glowing, but still place her writings secondary to her sister, Dorothea. I’d definitely have to disagree, having read both of Emily’s Transylvanian titles for this blog.

Her writing about folklore has given us all those brilliant vampire tropes we are so familiar with today. There’s death by a vampire creates another vampire, and bloodsucking as sustenance. A stake through the heart will kill a vampire, as will cutting off the head of a suspected vampire and placing it back in the grave. Garlic is a good means of warding off the undead.

My old goth has been reignited to the extent of having a reread of Dracula with a classic 80s goth soundtrack of Bauhuas, The Rose of Avalanche and an assortment of Rose McDowall’s post-Strawberry Switchblade outings. I’m also wondering what Emily would have thought of the world of shiny vampires brought to life by the Twilight movies or the abjectly bleak horror of The Strain.

Over a century later, I hope she’d enjoy how we’re still being entertained and enthralled by the folklore she shared with the world.

Want to read more?

Jedburgh Abbey in the late-1800s. Emily Gerard may have had childhood memories of this scene. Much of her writing, however, was shaped by her experiences in Europe.

The full text of The Land Beyond the Forest is available to read through Project Gutenberg. Alternatively, you can stay in the Borders for some more vampire-like activity, this time from Melrose Abbey.

Has Emily Gerard’s career has inspired you to seek out more trailblazing women travel writers? If so, take a tour of Scotland with Sarah Murray and Dorothy Wordsworth.