When we reflect on how we commemorate the First World War, we’re likely to think of memorials or services of remembrance in honour of the thousands of soldiers who fought and died abroad. But we can also look closer to home, where a huge civilian workforce mobilised to assist in the war effort. One example is the production of munitions at Eastriggs, on the northern shore of the Solway Firth.

Eastriggs and the 1915 Shell Crisis

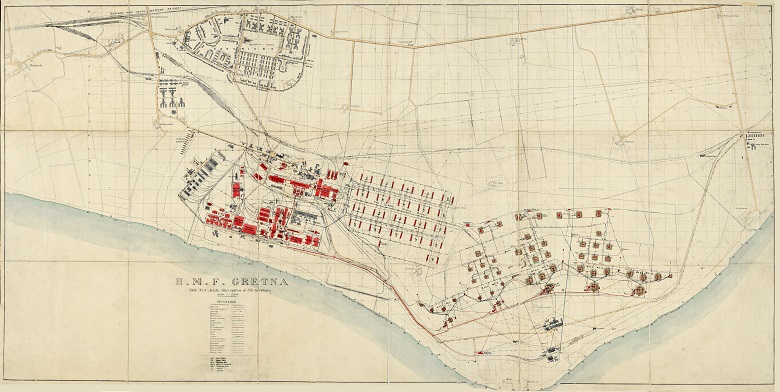

A map showing the scale of HMF Gretna, of which Eastriggs was a part (image courtesy of The National Archives)

In 1915, a shortage of artillery shells on the front line led to a political dilemma known as the Shell Crisis. The government responded to a need for huge quantities of munitions with a nationwide production programme.

This included building the largest munitions factory in the world, His Majesty’s Explosive Factory, Gretna. Here, a refined type of munitions propellant called cordite was to be produced.

The 1000-hectare Eastriggs site, where the cordite production process started, was at the western end of a 9-mile long cross-border complex. It ran from Longtown in England to Dornock in Scotland.

Producing “The Devil’s Porridge”

The numbers involved with production at Eastrigg are staggering. More than 600 wagons arrived by rail each day to deliver raw materials. They were processed to produce ‘gun cotton’. This made its way east to Gretna and Longtown to be finished as explosive cordite.

The railway terminal at Eastriggs

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote about the process in his capacity at the War Propaganda Bureau. He is attributed with coining the phrase ‘Devil’s Porridge’, used to describe the appearance of the gun-cotton and nitro-glycerine mix used in producing cordite. Today, that name is used by the local museum in Eastriggs.

A key figurehead was the Ministry of Munitions chemical engineer Kenneth Bingham Quinan. He recruited chemists and technical experts who developed a highly complex production system, made simple by breaking down the process into constituent parts.

The choice of a site along the inner Solway Firth was based on what was described at the time as ‘war factors’. Relatively inaccessible by land, sea, and air by enemy forces, it was undeveloped with sufficient space for over 470 structures. There were good mainline rail links and, critically, access to large quantities of fresh water.

The factory’s location beside the Solway Firth was chosen based on numerous “war factors”

More than 50,000 tons of cordite was produced annually. Prime Minister David Lloyd George publicly thanked Quinan in the House of Commons:

It would be hard to point to anyone who did more to win the war than Kenneth Bingham Quinan.”

Housing the workforce

As well as helping us understand factory design and construction, Eastriggs has also proved to be a fascinating microcosm of many of the wider social issues of the day, from workers’ housing and welfare to the changing role of women.

Once the decision to build such a vast factory had been made, urgent plans were needed to house the workforce and their families. Thousands of skilled and unskilled workers were drawn from across the Empire.

New settlements were built for the factory workers. These houses in Gretna are former worker’s huts converted into bungalows.

Architects Raymond Unwin and Courtenay M Crickmer were instrumental in the rapid design and construction of two new settlements at Eastriggs and Gretna (next to the well-known Gretna Green).

The self-contained settlements were built on farmland and comprised timber huts with brick built houses. They were laid out in a regular pattern along a central avenue. Each came complete with community facilities such as shops, churches, recreation space and a hospital.

Women at war

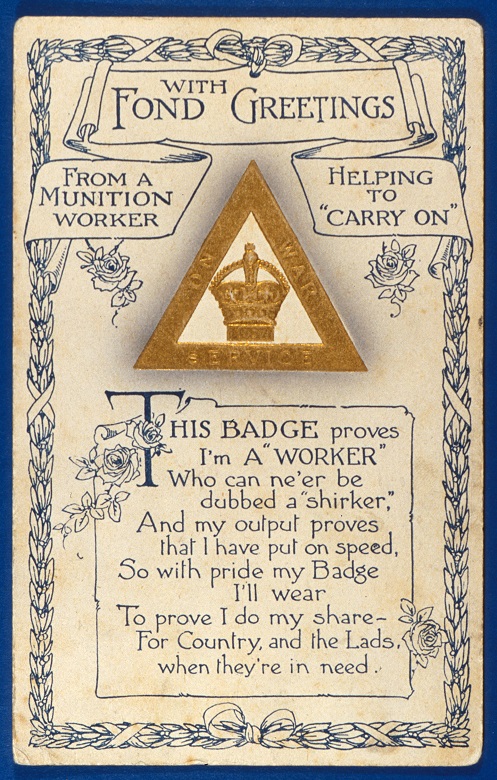

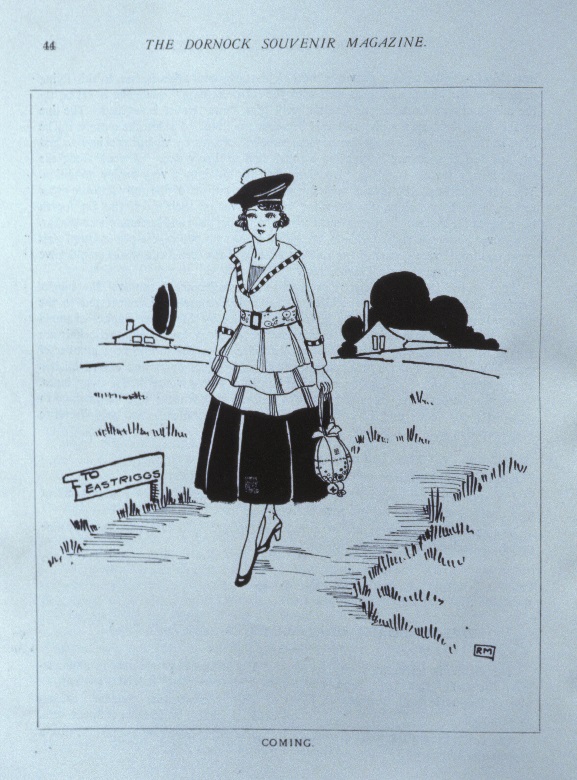

Of the total workforce at HM Factory Gretna, around 12,000 of the workers were women. Women were not new to the world of work in 1914, but the outbreak of war offered them a greater variety of opportunities than ever before.

Women were employed across the munitions factory site in a variety of roles ranging from manual labour to hospitality. There were roles in domestic service, medicine, chemistry, firefighting and policework. Many were young and living and working away from home for the first time, often in highly demanding roles.

A Christmas card produced by the workers at Gretna. (© Dumfries & Galloway Council. Licensed via Scran).

At Eastriggs and elsewhere across the UK, the expanding female workforce saw the creation of new leisure and recreation activities. Women’s sports clubs popped up in Gretna, including the Mossband Swifts and Gretna Girls footballers, and the Dornock Hockey team.

Social clubs and concerts were also popular ways for men and women to unwind after physically and mentally demanding days. That said, such activities were largely segregated from the men and were policed to ensure women’s morals were upheld.

When the war ended and servicemen returned to their jobs, many women found that these jobs and sports teams were closed to them again. It would take the re-ignition of the Women’s Suffrage Movement and the eventual enfranchisement of women to rediscover these freedoms.

A cartoon from the Dornock Souvenir Magazine depicting a woman coming to work at Eastriggs. (© Scottish Life Archive. Licensed via Scran).

The second part of the cartoon shows the woman leaving work with a fur coat, hats and a servant. While males were mostly paid a fixed salary, the women were paid overtime. The cartoon expresses the men’s envy at their high wages (© Scottish Life Archive. Licensed via Scran).

Recording and recognising Eastriggs

Let’s fast forward to the present day. At the request the local council, our Designations Team recorded the physical remains of the factory and assessed their heritage significance.

From industrial experts to UAV pilots, several HES colleagues visited the site over a two year period. Their combined work helped us to better understand the changes to the site in the 107 years since construction began.

After the First World War, much of the infrastructure was taken down and partly recycled for use elsewhere. Some areas were auctioned off and the land converted back to agricultural use. Further changes took place when the site was requisitioned as a munitions store during the Second World War.

This significantly changed the look and layout, transforming the complex industrial plant into a more uniform site. More than 100 simple buildings and huts were surrounded by earthworks to protect against unintended explosions. Further changes were made after the Second World War to modernise the facilities. They stayed in use as a munitions store up to around 2010.

To the archives!

Once our survey and assessment work was complete, we consulted several archives and found a treasure trove of related documents. There were architectural plans and construction notes, along with government files, historic imagery and contemporary accounts of life at Eastriggs. From an archaeological perspective, material from these archives was invaluable in helping us interpret what we were seeing on the ground.

In a little over eight months, we assembled a very good understanding of how the First World War site was constructed and operated, as well as how the complex was repurposed over the following century. The results are available on Canmore, along with a gallery of aerial photos.

Combining the results of our fieldwork with information from the various archives lead us to a clear conclusion: there are elements of the Eastriggs site that are nationally important because of their cultural significance.

Surveying a Brine Tank Tower at Eastriggs. It is the only survivor of five towers which stored salt water, a vital coolant in the nitroglycerine production process.

A grave reminder

Munitions and their constituent parts, like the cordite Eastriggs produced, were a chief cause of mass casualties on both sides. They’re a grave reminder of the human impacts of industrialised war.

But Eastriggs plays an important role in our understanding and recognition of the home front, industrial scale response to the demands of the First World War. The site played a significant part in the outcome of the conflict, and in the development of explosives. The factory exploited emerging ideas in manufacturing, such as the breaking down of production into smaller, key stages along a logical sequence or flow.

The components that best demonstrate the industrial processes that took place here have been designated as a scheduled monument. This covers five parts of the site responsible for glycerine distillation, acid mixing, nitro-glycerine production and gun cotton mixing, all of which went into producing cordite. Furthermore, the original gate complex forming the main entrance to the factory has also been designated as a listed building.

On this project, we’re fortunate to have had the help of the Defence Infrastructure Organisation, Historic England, Dumfries & Galloway Council, the Devil’s Porridge Museum, archives in Carlisle, London and Edinburgh and the local communities around Eastriggs. Without their collective help, this huge undertaking would simply not have been possible.

There’s even more investigations and designations around the blog. For instance, you can stay in D&G and join us on the trail of the old Blackcraig Lead Mines.