Did you know that ice skating was invented in Scotland? Well… sort of…

People may have been sliding on ice for thousands of years. But Scotland has some bragging rights when it comes to sporting pursuits on ice. Curling is, of course, a very much loved sport in Scotland. Head to the Scottish Curling website for an overview of the history of curling in Scotland.

But today we’re looking into Scotland’s part in the birth of figure skating, and one of Scotland’s most famous paintings keeps this legacy alive…

Reverend Robert Walker (1755 – 1808) Skating on Duddingston Loch by Sir Henry Raeburn. © National Galleries of Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Sliding back in time!

Archaeologists have unearthed evidence of cultures around the world using animal bone skates stretching as far back as the Early Bronze Age. These would have been strapped to existing footwear and used to get about when it was icy under foot.

A bone ice skate, made from a horse foot bone. It probably dates to the late late 13th or early 14th century. It was found during excavations in the medieval burgh of Aberdeen 1973-81. © Aberdeen City Council. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Interestingly, a 1928 essay chronicling the changes on the Isle of Lewis notes that sturdy shoes (not skates) would be worn in the snow and ice.

“Nam biodh casan fir fuar, bheireadh e fàd à bàrr an teine is chàireadh e fo chasan e san t-suidheachan. Cha fhreagradh brògan ach ri sneachd is reothadh. Bha iad math san àm sin gu spèileadh nan lòn, ach cha robh mòr fheum ann am fear nam bròg air blàr iomain.”

[If a man’s feet were cold, he would take a peat from the top of the fire and place it under his feet as he sat in the chair. Shoes were only necessary for snow and ice. They were useful in those times for skating on the lochs, but there wasn’t much use for a man wearing shoes on the shinty pitch.]

Another Scottish link is that the word “rink” comes from Old Scots. The Oxford English Dictionary notes that the word first appeared in the late 14th century to refer to a measured area for combat, jousting or racing. As far as we know, it wasn’t until the late 19th century that the word rink was adopted by English speakers. The word probably originated in Old French renc, which was a row or line.

But for all the thousands of years of skating that had been going on all over the world, it was the Scottish gentry who first had the presence of mind to set up a club (for wealthy men only, of course!) to celebrate the pursuit of figure skating.

The Edinburgh Skating Club

Most historians agree that the Edinburgh Skating Club was founded in the early 1740s (either 1742 or 1744), although the exact date is unknown.

The first list of members was recorded in 1778, and it reads as a who’s who of Edinburgh’s high society during the late Enlightenment. Aristocracy, advocates, architects, writers, surgeons, and wealthy merchants are all represented on the list.

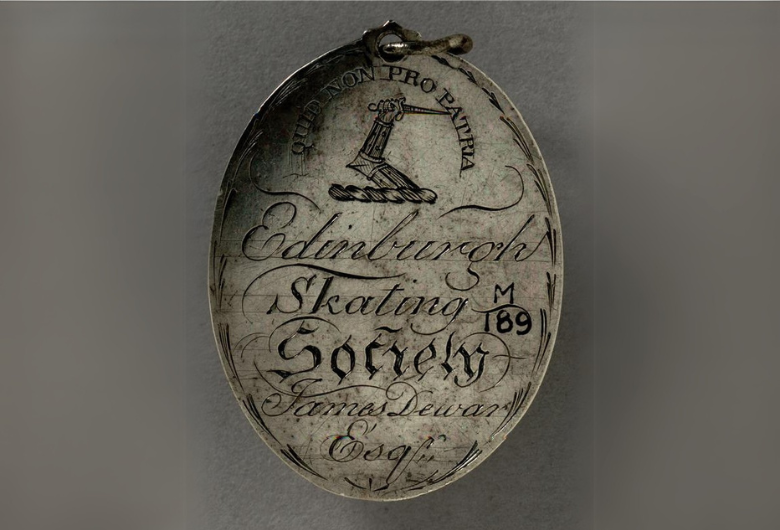

In 1789, members paid an entrance fee of £2 and 2 shillings. Probably the equivalent of between £250-£300 today.

Members of the club would receive a silver medal upon joining. This one dates to around 1790, t and was made for a James Dewar. © National Museums Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

But the members didn’t just have to have the money to join. They also had to be exceptional skaters. By 1865, it had become tradition for the candidate, after skating a complete circle on each foot, to jump over “first one hat, then two, and then three, each on the top of the other.”

If you’d like to know more about the Edinburgh Skating Club, you won’t get a more complete account than Margaret Elliot’s comprehensive article in The Book of the Old Edinburgh Club from 1971. Much of the information in this blog is taken from her excellent article.

The Skating Minister

Perhaps one reason that the Edinburgh Skating Club is still widely remembered is because of the famous painting, The Skating Minister. It was bought in 1949 by the Scottish National Gallery. Today, it’s one of the most recognisable images in their collection.

Raeburn was a pupil of George Heriot’s School in Edinburgh.

Raeburn had been born in Edinburgh in 1756. He was educated at George Heriot’s School, known at the time as Heriot’s Hospital. After spending some time in London and Italy perfecting his talent, Raeburn returned to Edinburgh in 1787 where he began painting portraits of the rich, famous and important people of his day.

It’s likely that Raeburn painted this portrait some time around 1795. The subject of the painting is the Reverend Robert Walker.

Reverend Robert Walker

Walker was born in Monkton, Ayrshire. He’d moved to Rotterdam as a young child when his father was appointed the minister of the Scots Church in the Dutch city. It’s likely that Robert learned to skate on the canals of Rotterdam.

Records show that “Rev. Mr Walker of Cramond” joined the club in January 1780. He would probably have been a young man of 24 at that time. There is some debate over his date of birth, though. It’s generally accepted that he was born in 1755, but an earlier birth date of 1746 has been suggested.

The young minister made quite the impression on Edinburgh society. He had been made the minister at Cramond in 1776. In 1784, Robert was appointed the senior minister at the Canongate Kirk. This was a prestigious post, which includes the Palace of Holyrood House within its parish.

An engraving of the church at Canongate from 1788. Rev Walker as the minister at this distinctive category A-listed building on the Royal Mile. © Courtesy of HES. Take a closer look on Canmore.

When Walker died in 1808, Raeburn was named as one of the trustees of his estate. This could be a clue that the artist and the minister were good friends. There is no evidence that they had skated together but the painting certainly has an intimate and affectionate quality and may well be a memento of their close acquaintance.

Duddingston Loch

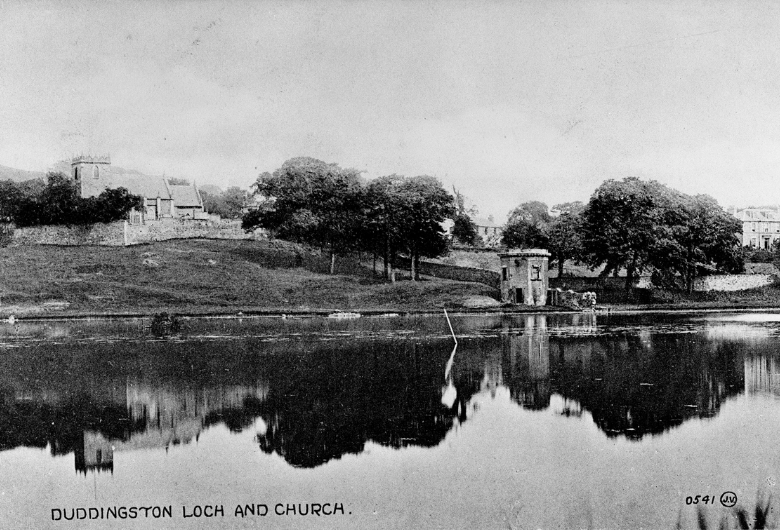

Although the club used various locations around Edinburgh for their skating, including Lochend and the smaller lochs in Holyrood Park, Duddingston Loch was their firm favourite.

Duddingston Loch with Thomson’s Tower and Duddingston Church on the far shore. Zoom in on Canmore. © Courtesy of HES.

Imagine witnessing the lively scene described in an 1865 history book of the club:

“There can be few more animating sights than a meeting of the Skating-club there on a clear bright winter’s day during a season of hard frost-enhanced as it is by the singular beauty of the locality, with the overhanging hill, the ancient church on the margin, and the fringing woods of the Marquis of Abercorn and Sir William Dick Cunyngham. The variety of occupation, too, adds to the excitement; the curlers, the shinty players, boys of all ages and in all states of delight — ladies walking or sliding or skating, admiring and being admired — and the occasional military band of music; while in some snug corner, with clear, black, smooth ice, away from the hurry of more violent performers, the members of the Skating-club enjoy their intricate evolutions, sometimes continuing far on in the short day, till the red glow of the frosty sunset is succeeded by the light of the rising moon.”

This wintry scene of ice skaters was taken about 1902 in Allan Park, Cults, Aberdeen. © Aberdeen City Council, Arts & Recreation Department, Library & Information Services. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Many club members also belonged to other Edinburgh societies, including the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. It’s amusing to think of them skating on Duddingston Loch before the Duddingston Hoard was discovered in 1778. Unbeknownst to them, impressive Late Bronze Age artefacts lay beneath their elegant figure-of-eights on the ice. The Duddingston Hoard became the first item registered by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, founded in 1780.

Dancing on ice

The Edinburgh Skating Club was renowned for its elegant appearance on the ice. Their goal was to be perfectly synchronised with their fellow skaters, interweaving in a circle.

The group’s history explains:

“The principal object of the Club is to enable the members to skate together in concert. This is done in figures. … These are numerous and varied. Some of them are very graceful. … The effect is produced by slow and graceful motion rather than by rapid and wonderful execution.”

To help their precision moves, the skaters would place an orange on the ice. This marked the centre they would skate around. Later, brightly coloured wooden markers were used instead.

A decorative banner for a dinner menu of the Edinburgh Skating Club from around 1895. © Scottish Life Archive. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.

Dedicated follower of fashion

Looking the part was also important to the Edinburgh Skating Club. A tall, top hat like the one worn by Reverend Robert Walker was a must for members.

However, by December 1884 younger members complained that:

“tall hats were inconvenient and out of fashion for such exercise as skating, and subjected them to the jeering smiles of their friends and onlookers.”

In an attempt at a compromise between the fashion-conscious youngsters and the traditional senior members, it was agreed that tall hats should be worn when the club met at Duddingston, but that at meetings elsewhere the members could wear a hat of their choice.

Safety

Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, club minutes show that Edinburgh surgeon, James Simpson (of maternity hospital fame), was particularly concerned about safety on the ice.

In 1814, the club agreed that their members would take an official role in ensuring safety on the ice. They bought some state of the art life-saving equipment. Along with the curling club, they agreed to provide watch person to “save the lives of boys and others who may accidentally fall through the ice.”

These days, there are very few winters in Edinburgh where our lochs freeze over enough for skating to be a safe activity. We’d definitely warn against venturing out on to any ice in Holyrood Park – even if you think it is safe!

The end of an era

There has been a lot of change in Scotland’s climate over the past few hundred years.

From around the 16th century to the 19th century there was a period where winters in Europe were incredibly cold. This was known as the Little Ice Age.

However, even in the 19th century, the minutes of the Edinburgh Skating Club show that the weather wasn’t reliably cold enough to freeze local lochs and ponds. Members were keen to find:

“a piece of ground in the neighbourhood of Edinburgh which could be overflowed with such a quantity of water as would freeze in the course of one or two nights sufficiently strongly to admit of skating upon it.”

By the 20th century, the outbreak of the Second World War contributed to the decline of the club. It was formally dissolved in 1966.

Sadly, with the impact of climate change, we’ve seen winters become increasingly warm throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century. These days, it’s incredibly rare that Edinburgh’s lochs and ponds ice over and even rarer that it is thick enough to skate on safely.

Scotland’s ice rinks

By the middle of the 19th century, the world’s first artificial ice rink had been opened in London, known as The Glaciarium.

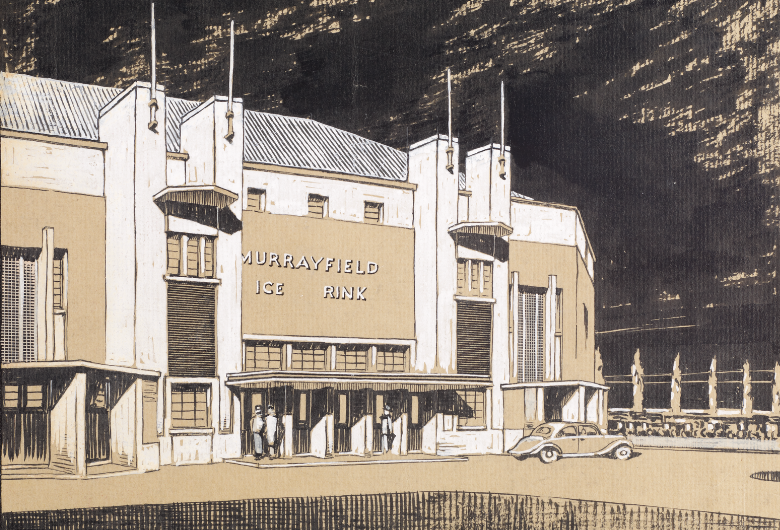

In 1907, Scotland’s first indoor rink was built in Glasgow at Crossmyloof. By 1912, two more rinks had opened. One in Edinburgh, the other in Aberdeen.

Say hello to the Skating Minister at the castle of light as he pirouettes around Hospital Square at Edinburgh Castle’s Castle of Light until 4 January 2025.

With thanks to the National Galleries for loaning his likeness to us for a bit of Christmas fun and Bright Side Studios for letting us reproduce their projection.