Scotland is proud of its water. Whether it’s our famous lochs (and the monsters within them), whisky distillery streams, or simply the quality that comes out of the taps. But did you know about its fascinating history when it comes to wellbeing? Many of us may know people who wax lyrical about the benefits of wild swimming. Or who love to participate in a New Year’s Day “dook”. But the idea of embracing the waters of Scotland for health and tranquility is far from new.

In the 1800s, hydrotherapy was the wellness trend of its day. Doctors and patients turned to cold-water treatments, ranging from ice baths to loch swims, as part of early therapeutic practices. Submerging yourself in chilly Scottish waters may seem a very different experience to a modern spa day, but it was the indulgent getaway of its time.

Although there is evidence of using water for health and wellbeing as far back as the ancient civilisations – and these therapies were used all over the world including Europe, Japan, America and New Zealand in the 19th century – Scotland became famous for its hydropathic hotels. It was a huge part of our hospitality and tourism during that time.

Often situated in picturesque rural locations, these buildings were as much about the view as the water. They promised both physical cure and mental calm. Scotland’s own take on water therapy became uniquely embedded in our history of tourism and medical innovation.

The Hydropathic Highlands

Water cures were seen as spiritually and physically beneficial. People travelled from all over Europe to stay in hydrotherapy hotels. Sometimes with dedicated medical staff on hand to prescribe and carry out treatments for conditions such as nervousness, diseases, gout, and rheumatism. Treatments included baths, the Scottish douche which was “discovered”, some argue, in the 1780s. Dr William Wright, suffering from fever on a ship, reportedly had “three buckets of sea water thrown upon him with just a cloak” twice a day for four days. He reportedly recovered after that. Other healing tactics include tonics.

Whilst guests at these hydros weren’t just pampered, they were often under strict supervision and alcohol was usually banned. Not that everyone took that rule to heart. One unverified but well-loved story recounts two Glaswegians preparing for a weekend at Rothesay Hydropathic by stopping at a local hostelry and requesting the landlady fill their “pistols and walking stick” with whisky before setting off: “As we’re gaun awa’ tae a place where we’ll get naething but watter, ye’ll better fill oor pistols and this wauking stick wi’ die ‘Auld Kirk’ an’ mak’ us ready.”

These stories bring a human warmth to the otherwise clinical reputation of these places. Hydrotherapy wasn’t just about medicine – it was about hope, adventure, and the enduring appeal of Scotland’s wild waters.

Historic Water Therapy Today

Today’s wild swimmers in padded towel jackets aren’t so different from the Victorians in their bath robes. The draw to the water to wash away the noise of busy life and submerge in a sense of calm grew quickly in popularity. If you visit these places today, you can still get an understanding of why this therapy is so effective.

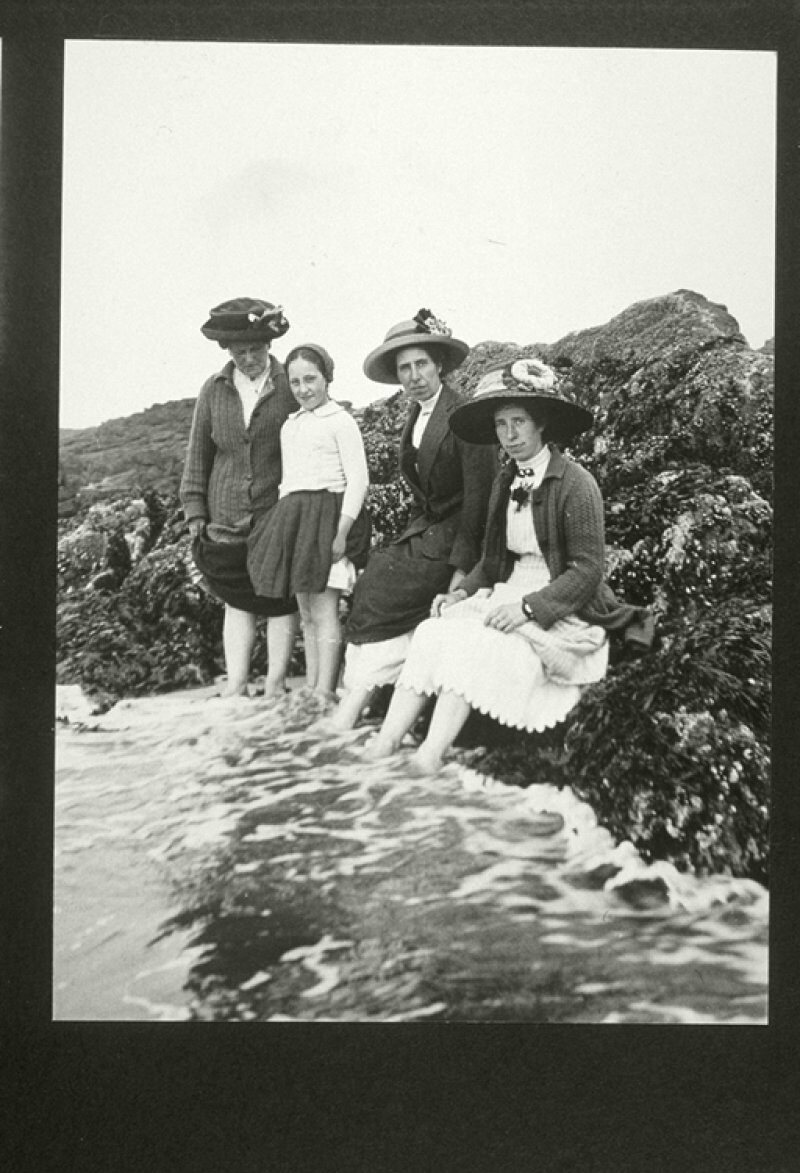

These women were photographed whilst on holiday in the Gullane area during August 1912. © Copyright: Glasgow University Archives & Business Records Centre (Records of the Scottish Cultural Resources Access Network (SCRAN), Edinburgh, Scotland)

The Craiglockhart site, for instance, now part of Edinburgh Napier University, was once one of Scotland’s most renowned hydros. During the First World War, it was repurposed as a hospital for soldiers suffering from shell shock, with water-based treatments among the many approaches taken. Renowned war poets Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon both received treatment here. The beautiful Victorian building remains intact, and the grounds featuring woodland paths and bubbling springs, offer a serene space for reflection.

Much farther north in the Highlands, you can visit the Victorian spa town of Strathpeffer. Following the discovery of its sulphurous springs in the 18th century, it became a fashionable destination for health-seekers. The last remaining pump-room is now a tourist attraction. Visitors can learn about the historical “water cures” for ailments like gout, rheumatism, and nervous disorders. Sadly, health and safety regulations now prevent visitors from tasting the iron rich or sulphurous waters. But you can still sense the place’s former splendour.

For a more bracing experience, continue north to Wick and dive into the Trinkie Tidal Pool. Carved into coastal rock and filled by the sea, it remains a favourite spot for hardy swimmers. While in the area, don’t miss the Castle of Old Wick. It’s one of our most striking medieval ruins, perched dramatically over the North Sea.

Holly Lodge. © Licensed by St Andrews University Library (project 813) (Records of the Scottish Cultural Resources Access Network (SCRAN), Edinburgh, Scotland)

Accessible water wellbeing in the Highlands

Artist Morag Edward’s recent reflections in The Power of Water: Sailing to the Historic Highlands capture another aspect of water for wellness. She describes how year-round swimming and sailing across Scotland’s seas and firths brings a profound sense of joy and emotional release. Especially for those facing physical or mobility challenges.

In her emotionally evocative account of enjoying being out in the water, Morag highlights a common issue with outdoor swimming enthusiasm: That elephant in the room is never mentioned in the increasingly popular sea swimming wellness write-ups and advice in the newspapers or medical articles or glossy coffee table books. Sea swimming is only good for your health if your health is good enough for you to get into the sea in the first place. It’s a cruel irony.

Morag’s firsthand account of facing accessibility issues is a reminder that there is a lot of work still to be done on widening the opportunities for all people to fully enjoy Scotland’s waters.

Listening to Water: Stories in Stone, Sound, and Silence

Not everyone needs to swim to reap the benefits of water. Sometimes simply being near a stream, loch, or waterfall is enough to pause, inhale, and reconnect. The Victorians built spas for immersion, and today’s wild swimmers find solace in Scotland’s open-air waters. But the true constant across centuries is the simple ability of Scotland’s waters to wash away noise and restore calm.

As part of Historic Places, Breathing Spaces, we are highlighting Fort George as a great place to explore how heritage can benefit your wellness. In her blog, The Power of Water, Morag recounts a magical moment near the fort: “Rounding Fort George, several dolphins decide to appear. Next to us. Right next to us. We slow to enjoy the treat… I try not to squeak with joy as they leap and jump and hunt.” These encounters remind us that the sea has the power to uplift in ways we can’t always explain but can deeply feel.

Share Your Water Stories

As part of your Historic Places, Breathing Spaces journey, we are inviting you to observe and appreciate the streams and lochs at our heritage sites and reflect on how they make you feel. Our online exhibition is gathering diverse stories of water and wellbeing.

Get Involved in Historic Places, Breathing Spaces

- Share: Upload a photo or video (up to 60 s) and a caption about your experience at a Scottish heritage site. Your contribution could feature in our online exhibition or on HES social channels.

- Explore: Discover guided walks, events, and Spotify playlists inspired by Scotland’s landscape and heritage.

- Be inspired: Read stories from real visitors, like Morag, who have found new meaning in our historic sites.

- Find your way: Access curated walking trails, staff favourite experiences, and practical wellbeing guides to help you start exploring.