Quoiting: The Search Begins

I was researching something completely different when I first came across the term Quoiting.

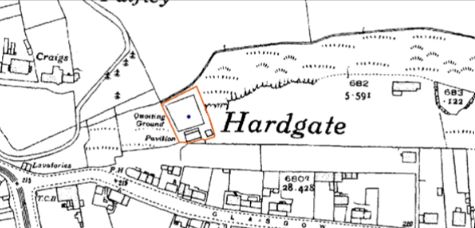

I was looking at a 3rd edition Ordnance Survey map when I stumbled on a small enclosure in the corner of a park, labelled ‘Quoiting Ground’. Over the following years I came across this again and again – but what exactly was Quoiting?

Its turns out that it was a sport, once popular in Scotland, where you throw metal hoops at a pin set in a square of clay.

I’d never heard of it. Even the National Record of the Historic Environment (NRHE) didn’t list any quoiting grounds in its extensive records. All we could find in the archive were three photographs of players and an image of a rubber quoit!

Hardgate Quoiting Ground with pavilion depicted on the 4th edition of the OS 6-inch map Dunbartonshire 1938, sheet nXXIII.7

The Long Game

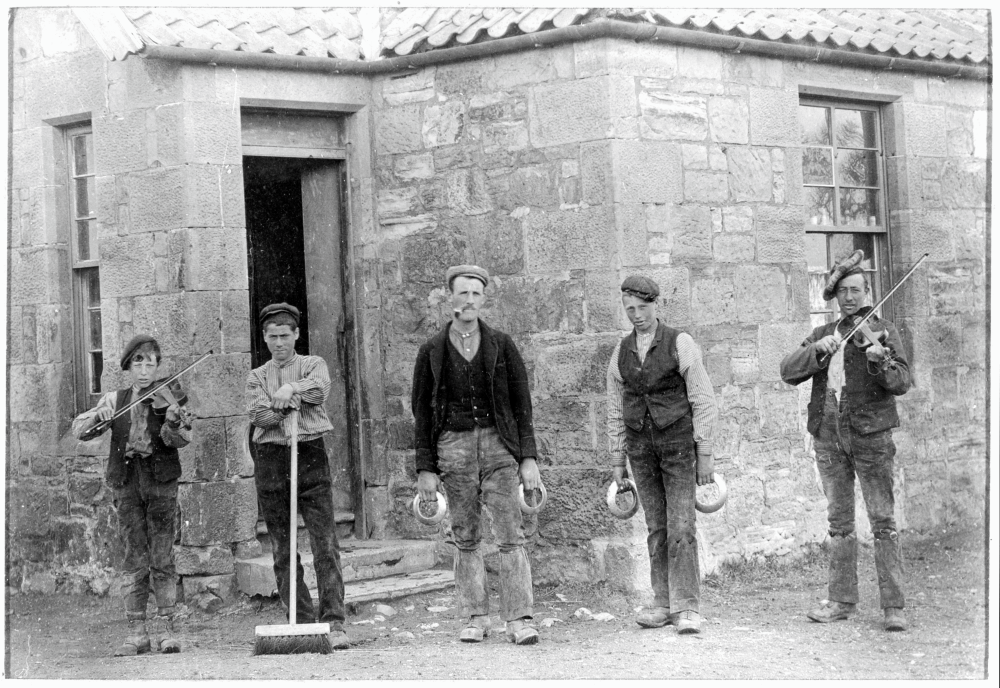

Established as a game since the early 19th century, quoiting was thought of as a working man’s game. With quoits weighing anything from 7 pounds to 17 pounds (or more!) ,over a distance 18-22 yards, it wouldn’t have been an easy throw. At the time, it was naturally thought that this was best suited to strong men who were used to hard physical labour.

A quoit is a flat circular iron hoop, sometimes with a personalised design for the individual player. In the traditional Scottish ‘Long’ game, quoits were thrown towards a metal pin inserted into an area of soft clay. The quoit would either stick in the clay or leave a mark. The closest quoit to the pin would win. It was sometimes described as a summer version of curling.

It appears to have reached a peak either side of the First World War. By the 1930s interest was already on the wane and after the Second World War many clubs had closed. At the time of writing this, Dunnottar Club in Stonehaven is the last remaining club in Scotland.

Annan quoiting ground can be seen with four clay pits visible on the east side. Shared pavilion with the adjoining bowling club.

A Dangerous Game

It seems that many of the quoiting grounds I found on the maps were clubs that rented, leased, or bought land to have a dedicated playing ground. Others didn’t, using common land by a river or more frequently, at the back of public houses or working men’s clubs and thus extremely difficult to find.

Those with dedicated quoiting grounds often had a club house, sometimes with a store for ground maintenance. The playing surface was normally an open flat area, often with an enclosure fence or barrier of some sort. This barrier served a second purpose of protecting the spectators.

After all, quoiting could be a dangerous sport. A stray 12-pound metal quoit could miss the clay or strike another quoit and hit someone. It was claimed there were no fatalities, but badly bruised or broken legs and ankles were common. The technique of throwing the quoit was individual to a player but required a steady hand and a good eye.

The players were often helped by a spotter, who would hold a piece of paper by the pin when the pin was partially or fully hidden from the thrower’s view. It was the spotter who was most at risk from a bouncing quoit. Games were often long affairs but ‘First to 21’ was used in international matches. However, in newspaper reports the score could exceed 60 in a match. Some matches lasted for many hours and finishing in darkness.

A Game of Professionals?

The popularity of the game meant that the results of these matches were printed in local and national newspapers. Cup competitions often brought together the best players; no doubt helped by prize money. A typical example reported in the Edinburgh Evening News in 1892 describes “A quoiting match for £20 was played at Loanhead”. This equates to a value of £2155 in 2025.

These matches could often bring significant numbers of spectators, especially exhibition matches. As ever, where there was money and sport, there was betting. Large and small sums of money were placed on individuals and teams. Many teams and competitions were helped by enterprising publicans who offered their pub gardens as a green and the pub as a club house!

The British Newspaper Archive is a gold mine for information on the clubs, local leagues, championships as well as providing some details on the locations of these clubs. Many towns had more than one club, such as Bo’ness and Bailieston. In a match programme for one of the last international matches, it talks of there being 300 quoiting clubs in Dumfries and Galloway alone.

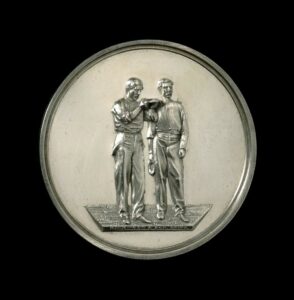

The sport was popular across the nation and descriptions of the matches often talk about extremely large crowds, especially for championship matches with the best players considered professionals. Prizes could be large, either cash or cups, presentation boxes and even silver quoits. Local, county, regional and national championships were often sponsored by individuals or by companies, like the national championship which was known as the “Glasgow Evening News Trophy”.

Medal for quoiting by Kirkwood, Edinburgh, c.1890. © Scottish Life Archive. Licensed on Scran.

Industrial popularity

My research suggested that the game was popular in industrial and farming communities, so looking at industrial towns for quoiting grounds was key: particularly mining towns and villages, where sports were often encouraged and thrived. However, despite my thorough search of the OS maps, sites were few and far between.

The main reasons are probably two-fold. Quoiting grounds were not mapped systematically by the OS as they did not meet the criteria for depiction; many being temporary in nature or located within a public park.

Secondly, it may be that certain OS map makers saw them as low value and did not bother mapping them at all. This certainly seems to be the case in Ayrshire where there are quoiting grounds depicted on maps, but they were not annotated as such.

Farm servants at ‘Big’ Kinnaird, near St. Andrews,1900. © National Museums Scotland. Licensed on Scran.

Sporting Decline: The Fall of Quoiting

As a sport, quoiting thrived for many years with clubs across Scotland, like Wanlockhead, established in 1828 with 100 members. It grew in popularity across much of industrial Scotland.

So how did we get to where we are today?

The slow demise appears to have started by 1920s, as clubs began to fold. Quoiting grounds disappeared as pressure on land by new developments accelerated in the post-war era. By the 1960s, the game was in terminal decline with fewer and fewer venues and clubs.

Regular international matches between Scotland, England and Wales were still common but as the long game disappeared in Southeast England, only Scotland and Wales played on. The last international match was in 2009. By the 1990s and into the 2000s, only 5 clubs remained.

The reason this sport has all but disappeared is probably down to a number of factors. Firstly, its image aligned with working-class roots. Quoiting was perhaps seen as a rough working man’s sport, associated with betting and alcohol. It failed to catch the enthusiasm of the growing middle class as the 20th century progressed.

Secondly, de-industrialisation. Mining and heavy industry decreased from the 1920s onwards, and combined with the rise of new entertainment such as cinema , TV and a huge increase in the popularity of other sports, particular football in the 1930’s. The sad fact is that a game played by many people for so long with such a rich tradition is no more. Its legacy has all but disappeared. But by recording its footprint in the NRHE we can record part of Scotland’s rich sporting traditions.

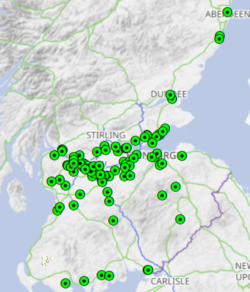

Map of known quoiting grounds across Scotland

Gone but not forgotten

While the sport is very rarely played today, its history should not be forgotten. We have now recorded the location of over 100 quoiting grounds on trove.scot, with sites from Aberdeen to Annan and Ayrshire to Fife. Almost all of which are depicted on old OS maps and available on trove.scot.

But my personal mystery continues, as this does not include that very first ground I found that inspired the Quoit hunt. As much as I have tried, I have not located it. The only clue is that it lay in a park with a steep terraced banking to watch the game. So, two challenges to anyone reading this is to find out about your local quoiting ground and help locate my missing one!

If you have better luck than me, we’d love to know!