For centuries, stained glass has been more than just decoration in churches. It has been a powerful medium for storytelling, spiritual reflection, and architectural beauty. In an age when most people could not read, these vibrant windows served as visual scriptures, illustrating biblical scenes and moral lessons in glowing colour. They transformed sunlight into a divine presence, filling sacred spaces with an atmosphere of awe and reverence. Beyond their spiritual role, stained glass also reflected the artistic and technological achievements of their time, and often bore the marks of the patrons who commissioned them.

Glasgow Cathedral is a remarkable example of this tradition. Though none of its medieval glass survives, the cathedral today houses one of the most diverse and evolving collections of stained glass in Scotland. The windows of Glasgow Cathedral tell a story not just of faith, but of time, taste, and transformation.

This blog traces the timeline of these windows, revealing how each generation has contributed to the cathedral’s ever-changing relationship with light.

Imagining Medieval glass

Construction began on the current stone cathedral in the 1200s, but sadly none of the stained glass windows from this time survive. The original windows were destroyed in the Protestant reformation of the 1560s. We are lucky the cathedral itself survived. After the reformation the windows were replaced with clear glass and remained plain into the 19th century.

An early 19th century engraving showing clear windows in the south transept at Glasgow Cathedral. Artist: E. Challis of T. Alloms. Find out more about Glasgow Cathedral on trove.scot

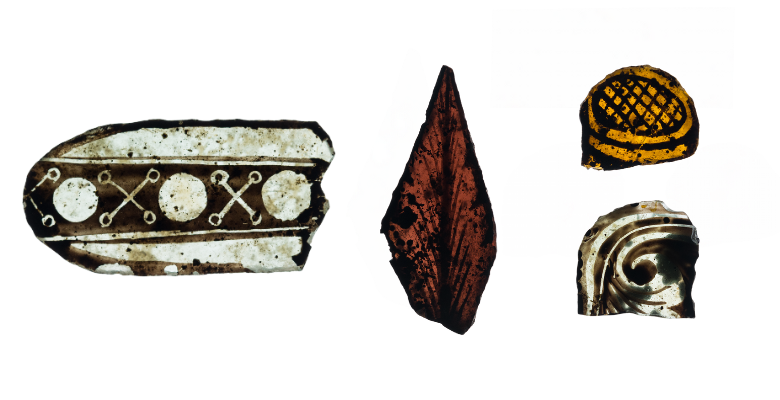

Although we have no way of knowing exactly what the medieval glass looked like, we can make an educated guess based on finds in excavations and contemporary glass in other religious sites.

Fragments of medieval stained glass found at St Andrews Cathedral. Explore more on trove.scot.

Light was of utmost importance in Medieval religious spaces. Sunlight was carefully incorporated into the design to illuminate sacred areas, represent the divine, and enhance the experience of religious rituals. The interiors of religious buildings were often painted white and decorative glass was used to enhance brightness. It can be assumed that Glasgow Cathedral was no exception.

Decorative glass would have featured biblical or religious scenes which may have come in the form of medallions in clear glass. Another common form is the grisaille type, a painted floral or geometric design on white glass (which had a yellow or green hue in the medieval period) with details picked out in colour with the aim of obtaining a jewel like effect. A fine surviving example of this can be found in the Five Sisters window in York Minster, but there are several 20th century grisaille windows to be found in the cathedral.

Victorian glass: Glowing colour and rich design

In the 19th century it was suggested that a building as significant as Glasgow Cathedral should be fitted with stained glass and so the process of changing the windows began.

Initially a small number of windows at the east end of the quire were filled in with coloured glass. This was then followed by the windows in the lower church, where a number of international artists were invited to contribute their work, including Pompeo Bertini of Milan and Ballantine and Allan of Edinburgh, who also provided stained glass for the House of Lords.

There was some disapproval at the lack of uniformity in theme and style of the artwork in the lower church, so a committee was drawn up to oversee the development of the windows for the main part of the cathedral. They decided that there needed to be an artistically unified scheme by a single group of artists.

Munich glass

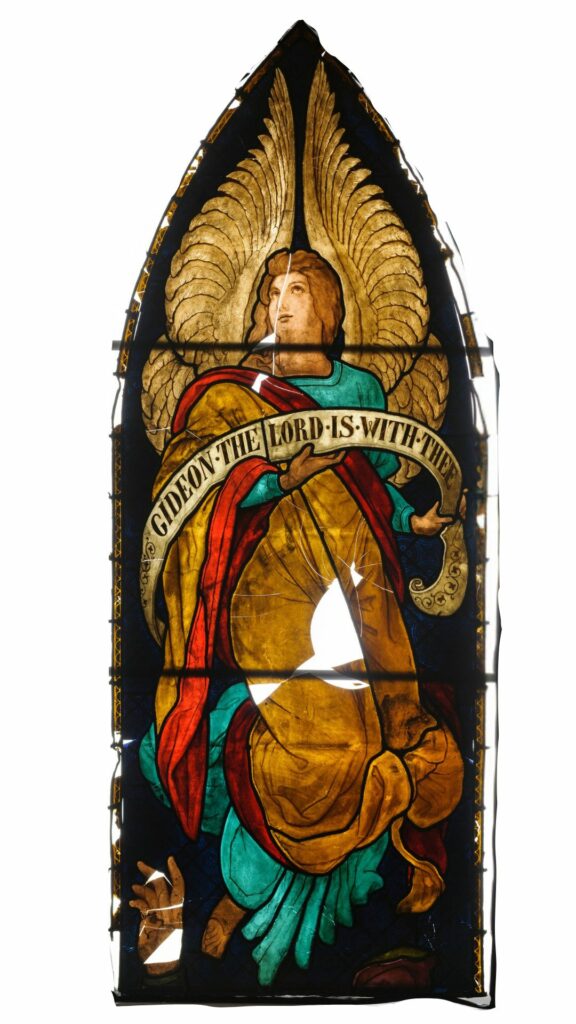

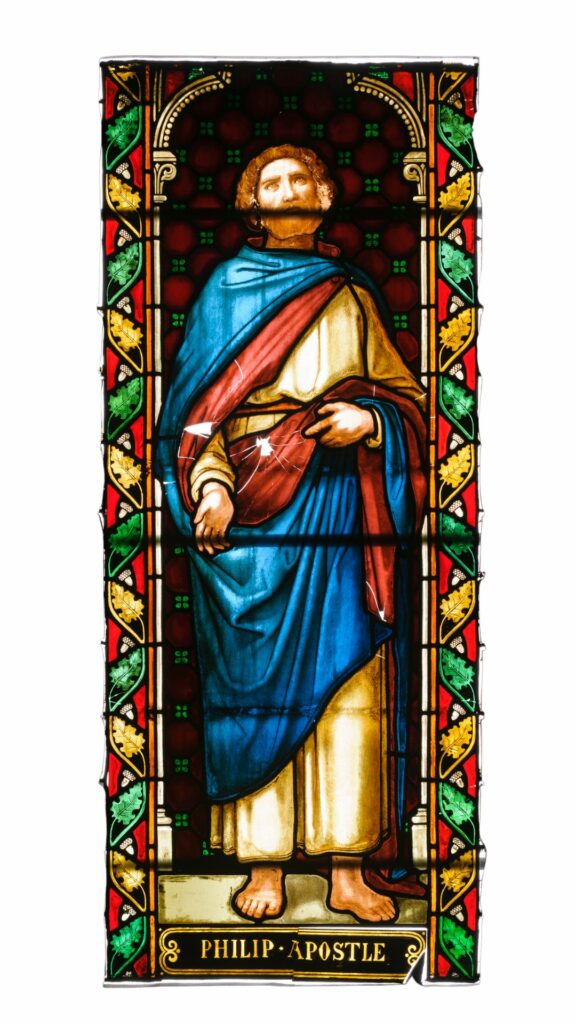

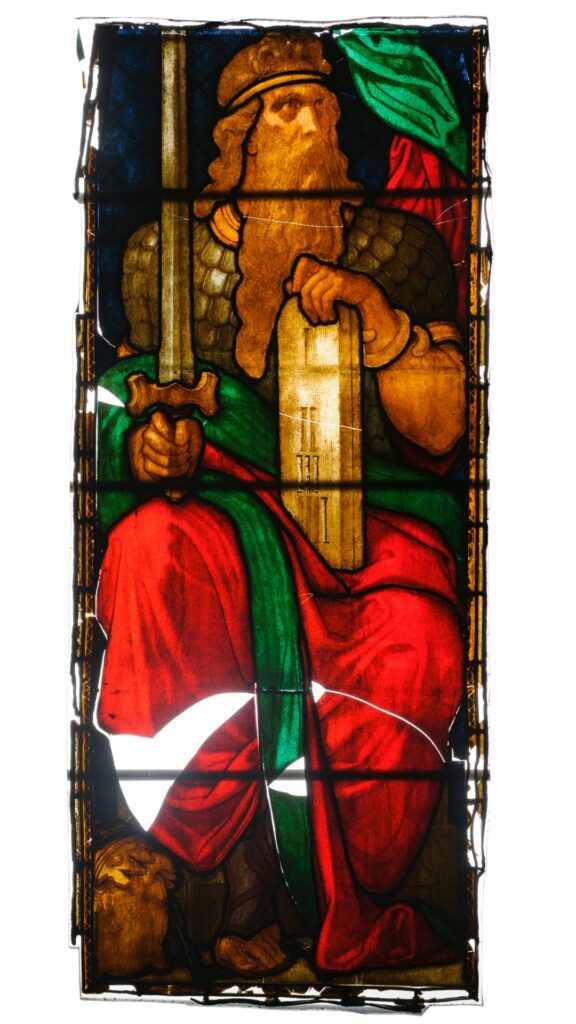

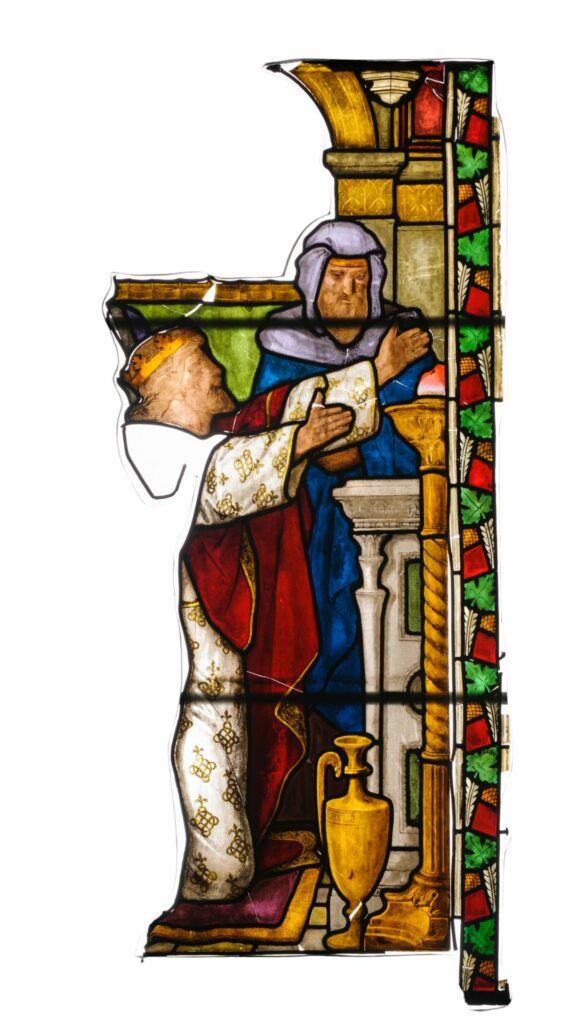

It was decided that the designs would be biblical and would follow a Medieval practice of putting Old and New Testament images together. The committee made the decision to award the contract to the Royal Bavarian Stained Glass Establishment in Munich, which was controversial at the time.

Although the expressive figures and rich colours of the Munich glass were admired by some, they almost immediately attracted criticism. The were seen as depriving the interior of light, making it difficult to see carved details in the stonework. It was even claimed that descending to the lower church could only be done “with difficulty”.

There were also concerns that awarding such a large contract to a foreign studio would discourage the growth of traditional skills in Scotland.

Unfortunately, the pollution in the atmosphere of industrial Glasgow, a factor that led to the blackening of the stonework, had led to the deterioration of the Munich windows. The painted details in the windows had suffered, and by the 1930s they were in poor condition. The dismay at the state of the windows meant a new programme of replacement would soon be under way.

The Munich Glass is now kept in storage in the Cathedral, but six lancets were left in situ and there are examples on display in the lower church.

Windows that were not produced by the factory in Munich still survive in the cathedral. These include windows in the sacristy originating in England and the rose window above the south door, which was designed and installed by the Glasgow company, W & J Kier.

The revived ‘Struggle for light’

In 1935 the minister of the cathedral, Nevile Davidson, founded the Society of Friends of Glasgow Cathedral. One of the key missions of the society was the replacement of the Munich windows. Recognising this would take many years and a not insignificant amount of money a national appeal was lodged and soon there were enough funds to pay for five windows.

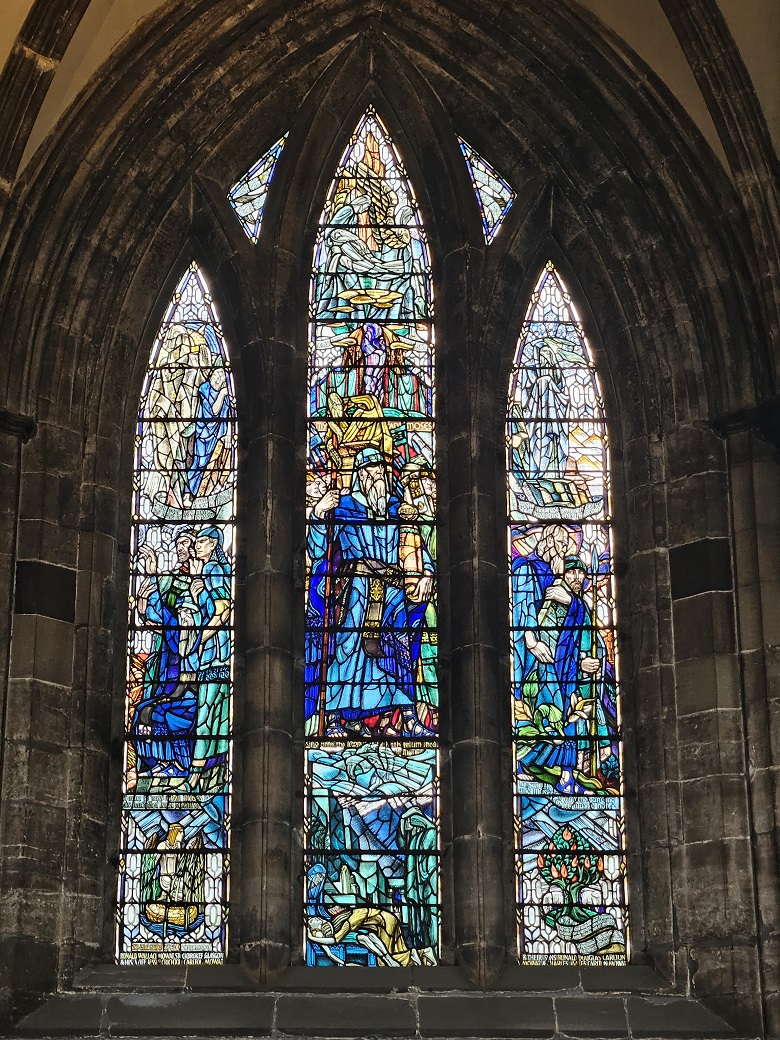

The first of the new windows was installed in 1936 and was designed by the Scottish artist Douglas Strachan. Although the colours don’t seem as vivid now, his Moses window was noted to stand out brilliantly next to the Munich windows. Prior to the First World War, Strachan received a prominent commission to design stained glass for the Peace Palace in The Hague. In the wake of the Great War he designed the stained glass at the Scottish National War Memorial.

The Moses Window by Douglas Strachan.

The war saw a disruption to the reglazing programme due to fear of destruction. However, one window was installed in 1940, “CHRIST and the WORLD’S WORK’, by Herbert Hendrie. It was hoped that the window would provide inspiration to the other artists who had already been commissioned. The window itself contains many modern details, incorporating depictions of industries that were found in Glasgow at the time.

The reglazing programme resumed after the Second World War, resulting in the creation of one of the finest collections of 20th century glass. The designs range from grisaille to biblical, and several feature the life of St Mungo, Glasgow’s patron saint.

London artist, Francis Spear, created the great East Window (1951) and the much-admired West or Creation Window (1958).

It was decided that the clerestory windows would remain clear to make sure the interior of the cathedral was as bright as possible.

The Next Generation

A decision of the committee formed in the mid-20th century was that not all the windows should be glazed so that each generation could add their own. Therefore, most of the windows in the nave were left clear.

The latest three windows exhibit great variation in style.

1999 saw the addition of the ‘Millenium Window’ by John Clark, centered around the theme of growth. It was joined in 2018 by the ‘Tree of Jesse’ window by Emma Butler – Cole Aikin.

The beautiful new 850 window by Talia Blatt.

Most recently, in June 2025, a new window by emerging artist Talia Blatt was installed to celebrate the 850 year anniversary of Glasgow’s burgh charter. It depicts the cathedral and its surroundings through the centuries.

The windows of Glasgow Cathedral will continue to evolve as they are slowly filled in the coming decades. Regardless of subject or style, one thing is certain; they will all seek to let in the light. The range of colour, details and style means that everyone has a favourite window – or two!

Help support our work

If the beauty of Glasgow Cathedral’s stained glass captured your imagination, why not buy a wee memento over on our shop?