This year, Glasgow celebrates 850 years since its official founding as a burgh in 1175.

Now Scotland’s largest city, Glasgow had a relatively late start on its journey to official recognition, compared to Scotland’s other cities. It’s elevation to burgh status was preceded by the likes of Elgin, Peebles, Dunfermline and Forres, which are much smaller cities and towns than Glasgow today.

So how did Glasgow become one of the most important places in Scotland? Who influenced its growth? And why is Glasgow Cathedral so important to this story?

Glasgow Cathedral.

Content warning: This article contains references to sexual violence, including rape, which may be distressing to some readers. Please take care while reading.

The booming of the Burghs

Glasgow’s earliest origins trace back to a time before the formation of Scotland itself. The city’s early history is deeply intertwined with the spread of Christianity and the gradual consolidation of power by both secular and religious leaders.

Before the 12th century, the population of Scotland lived in scattered hamlets with larger communities forming around monasteries like Dunkeld and St Andrews, or near important fortifications like Edinburgh Castle and Stirling Castle.

It was King David I (1084-1153) who introduced the first burghs, after he became king in 1124, starting in Lothian and expanding into Gaelic regions by 1130. Burghs were a way for monarchs to allow localities to govern themselves to a certain extent, while bringing in money to the royal coffers and making clear who had the ultimate gift of power.

A burgh charter gave the burgh legal status and spelled out its rights. For example, holding markets, collecting taxes, or trading. It also brought in terms that we still use today such as gait, wynd, provost and vennel.

For royal burghs, the charter gave them additional special powers, including the right to trade internationally and send representatives to Parliament.

King David’s successors, Máel Coluim IV and William I, extended the system further, founding burghs in places like Inverness, Dundee, Lanark, Dumfries, and Ayr. By 1210, Scotland had around 40 burghs, with more added by the time of the Wars of Independence.

St Margaret’s Chapel is the oldest standing building in Edinburgh, built around 1130 by King David I for his mother, Queen Margaret.

King David’s diocese

In 1113 David took control of his inheritance, and became Prince of the Cumbrians, ruling over vast swathes of what is now Southern Scotland, whilst his half-brother Alexander ruled as King of Alba.

As someone with a claim to the throne, David needed to establish his own powerbase and he identified the small settlement that had developed around the religious site on the banks of the Molendinar Burn for this.

At the time, Govan (on the southern banks of the Clyde) held the most important religious status in the area. It was also linked to a different royal dynasty: the Kings of Strathclyde. David rejected this, in favour of going his own way and very quickly the importance of Govan declined.

Dumbarton was the capital and chief fortress of the Kingdom of Strathclyde.

David re-established the diocese of Glasgow, installing his tutor and confidant John, as Bishop of Glasgow in or soon after 1114. He also assigned the diocese much of the land within his control which increased both the episcopal see and its income (which would eventually see Glasgow become the second most important bishopric in Scotland).

Together, King David and Bishop John worked to assert the independence of this new Scottish Church, challenging the authority of the Archbishop of York and generating tension with the English church.

John set about constructing a cathedral church at Glasgow and by 1136 it was in a sufficiently finished state for a dedication to be carried out, although it would not have been a large building.

Divine intervention

Following the death of Bishop John, Herbert assumed the bishopric in 1147 and continued to consolidate power around the cult of St Mungo. He commissioned the first biography (or hagiography) of the saint.

In 1164, the powerful Norse-Gaelic ruler, King Somerled, sailed up the River Clyde with a large fleet, hoping to take the Scottish throne. As his fleet approached Glasgow, legend tells that Herbert prayed at the tomb of St Mungo for divine intervention.

Detail of stained glass window at Armadale Castle depicting King Somerled.

Following this, Herbert may have well travelled to the Battle of Renfrew, where Somerled was ultimately defeated. Legend tells that Somerled’s severed head was brought to Glasgow Cathedral and Herbert proclaimed, “The Scottish saints are truly to be praised!” Herbert himself may have been mortally wounded during the battle as he died not long after.

This dramatic defeat of an invading force elevated St Mungo’s status in the national consciousness.

Who was St Mungo?

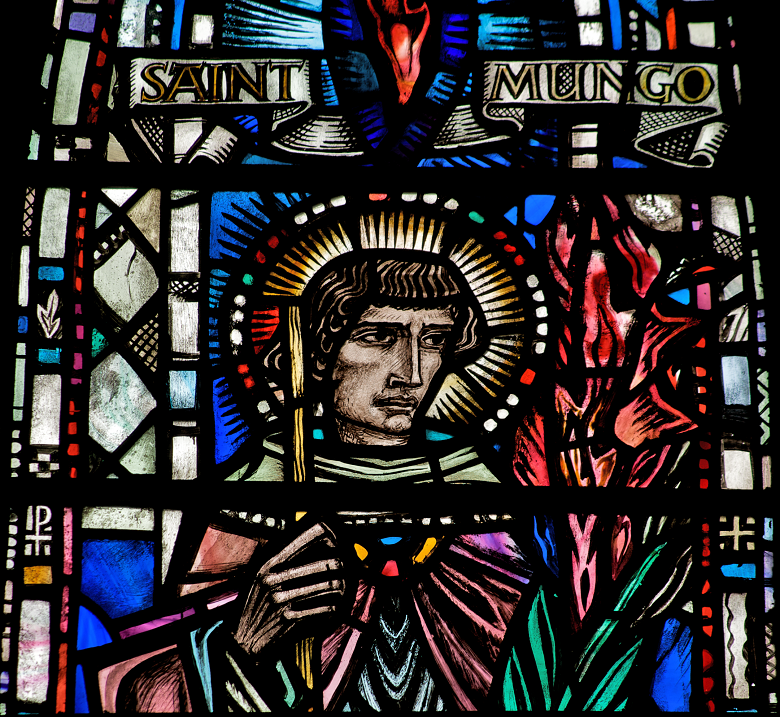

At the heart of Glasgow’s origin story is St Mungo, also known as St Kentigern. A missionary and holy man of the late sixth century, Mungo is believed to have died in 614AD (possibly at the remarkable age of 95). He is revered as the patron saint of Glasgow.

Saint Mungo depicted in stained glass at Glasgow Cathedral.

His story begins with his mother, a princess named Thenew (also spelled as Teneu, Thaney, Teneu, and later called St Enoch). Thenew was cast out by her father, the King of Lothian, when she was raped and became pregnant. The historian Dr Elspeth King describes St Enoch as “Scotland’s first recorded rape victim, battered woman and unmarried mother”. Miraculously surviving a fall from a cliff, she was carried across the Firth of Forth in a boat with no oars, eventually arriving in Culross, Fife.

Mark Worst’s mural of St Enoch in Bridgeton.

There, she was taken in by a holy man named St Serf, who became a mentor to her son, Kentigern. Serf affectionately nicknamed the boy “Mungo,” meaning “dear one.” Under Serf’s guidance, Mungo grew into a devout Christian and a powerful preacher.

Among Mungo’s many miracles is the tale of the robin: when classmates accidentally killed St Serf’s pet bird and tried to blame Mungo, he prayed over the bird and brought it back to life. This miracle, along with others involving a tree, a bell, and a fish, are immortalised in Glasgow’s city crest.

From missionary to bishop

Eventually, Mungo seems to have decided to make his own way and established a religious centre of the banks of the Molendinar Burn. The burn still runs through the modern city of Glasgow. Today, it is mostly invisible, hidden below the streets of the city. A map from the end of the 18th century shows the burn running down the route of Wishart Street, which runs alongside the cathedral precinct today.

This map of Glasgow from 1795 shows Glasgow Cathedral (kirk) by the side of the Molendinar Burn, which now mostly runs under the streets of Glasgow. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’ (Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Mungo was a powerful man in his own lifetime, it is said he evangelised the Strathclyde Britons. He became bishop of an area that corresponded with the Kingdom of Strathclyde, stretching from Ben Lomond in the north to the Rey Cross, between Penrith and Barnard Castle, in the south.

Jocelin and Jocelyn

Bishop Jocelin’s appointment and ambitions

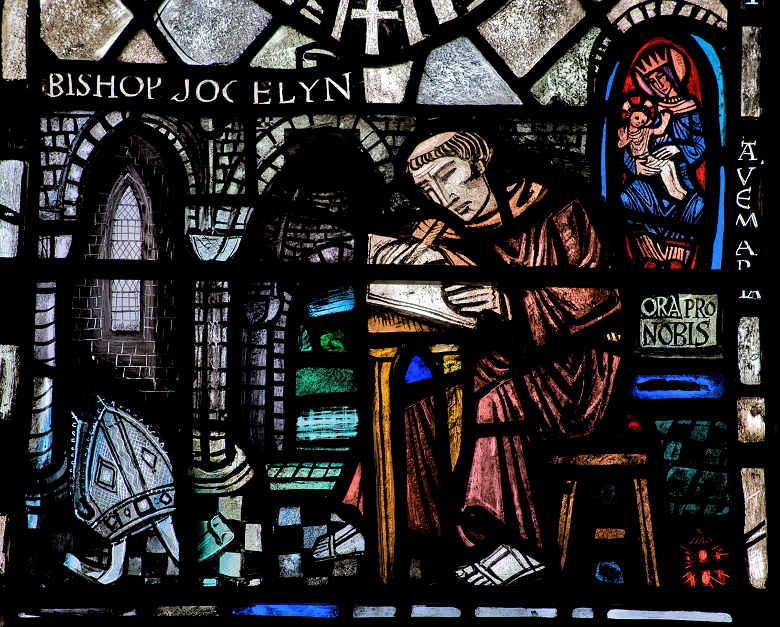

In 1174, Bishop Jocelin was put in charge of further increasing the power base in Glasgow. He had lots of experience and impressive credentials, having been the abbot in charge of Melrose Abbey. His election as Bishop of Glasgow likely took place in Scone, under the watchful eye of King William I, also known as William the Lion.

Bishop Jocelyn depicted in stained glass at Glasgow Cathedral.

Jocelyn of Furness and the power of storytelling

To expand the church’s influence in Glasgow, Bishop Jocelin needed both financial backing and political support. He set out to persuade patrons of the site’s deep historical and spiritual significance. As part of this effort, he enlisted another Jocelyn (Jocelyn of Furness) to write a new hagiography of St Kentigern. This biography not only elevated Mungo’s status as a miracle-working saint but also firmly established his role in Glasgow’s origin story, reinforcing the region’s long-standing ties to Christianity.

Jocelyn of Furness was a Cistercian monk based at Furness Abbey in Cumbria, renowned for writing biographies of saints. It’s likely he also popularised the tale of St Patrick driving snakes from Ireland. He had also previously worked with Bishop Jocelin at Melrose to encourage the cult of Waltheof, the second abbot of Melrose, who was elevated to sainthood thanks to the activity of the Jocelyns.

Melrose Abbey, where Bishop Jocelin held a previous post.

Some of what Jocelyn of Furness wrote seems to bear the hallmarks of truth. But later scholars have identified inconsistencies with other sources that suggest confusion or embellishment. We’ll leave it up to the reader’s interpretation as to whether these contradictions stem from honest attempts to interpret fragmented, centuries-old sources or from deliberate efforts to enhance the saint’s legend for political and ecclesiastical gain.

By 1181, and likely supported by increased patronage, Bishop Jocelin was ‘gloriously enlarging’ the cathedral, which likely took the form of a cruciform extension around the high altar and St Kentigern’s tomb in the crypt below.

Mungo makes Glasgow

Glasgow Cathedral is said to stand on the site where St Mungo founded his church and where he was later buried.

In the version of the story told by Jocelyn of Furness, young Mungo left the monastery in Culross and was led to Glasgow by an ox-drawn hearse carrying the body of another holy man, Fergus. Mungo is said to have said that where the oxen stopped would be the burial place.

A depiction of St Fergus’ remains on the ox cart in the Blacader Aisle at Glasgow Cathedral.

Jocelyn recounts:

“The saint took down the holy body in that very place, and having performed the funeral rites, he surrendered the dead to that cemetery in which no man had as yet been laid. This was the first grave in that place in which afterwards many bodies were buried in peace. The greatest reverence was devoted to the tomb of the man of God; nor was his grave taken for granted by any bold man daring to trample on it or rashly going over it. For before the turning of the year, many who had tread on his grave or despised its reverence were punished with some serious misfortune, and some even with death. That grave mound even up to the present is girded with a delightful thickness of overhanging oak trees as a mark of the holiness and reverence of the dead man.”

We don’t have much early evidence for Mungo’s church on the site now occupied by the cathedral, and we do not have any artefacts dating from this time from the area. However, burials orientated east-west (indicating that they were Christian) and dating to between AD 677 and 860 have been found on the site.

Growing Glasgow’s power

The successful promotion of the site as a shrine to St Mungo throughout the 12th century certainly contributed to Glasgow’s evolution. Cathedrals were more than just places of worship; they were hubs of governance, education, and even social activity.

In 1175, Bishop Jocelin was granted a charter by William I to make Glasgow a Burgh of Barony and to hold a weekly market. In the same year, Pope Alexander III recognised Glasgow as ‘a special daughter’ of Rome, freeing the diocese from the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of York. Glasgow had arrived!

St Enoch: Glasgow’s matriarch

While St Mungo is celebrated as Glasgow’s patron saint, his mother, St Thenew (more commonly known today as St Enoch) also holds a special place in the city’s story. Though her life is shrouded in legend, she is remembered for surviving sexual violence, exile and hardship to raise the boy who became one of Scotland’s most revered saints.

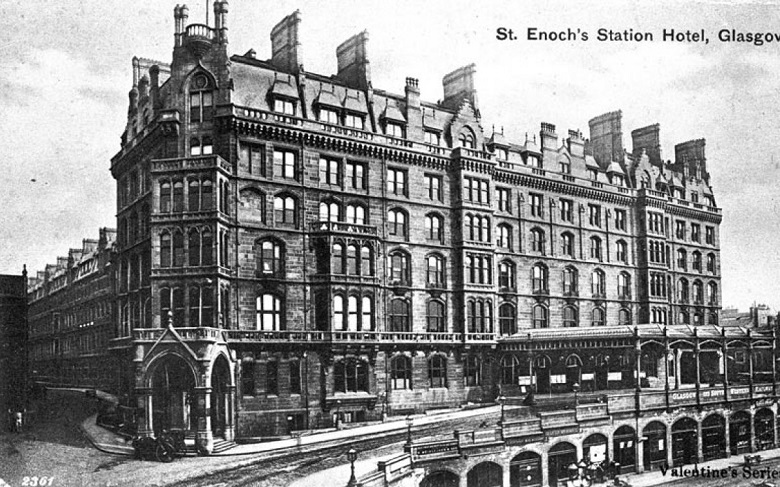

Her legacy lives on in the heart of Glasgow. St Enoch Square is supposedly the site of a medieval chapel dedicated to her, built on or near her grave. And until 1926 a church stood on this spot dedicated to the saint.

The area also once housed St Enoch railway station and hotel, a grand Victorian terminus that operated from the 1870s until its closure in the 1960s. This was replaced with the St Enoch Shopping Centre, which opened in 1989.

St Enoch’s Station Hotel was demolished in 1977. © Licensed by St Andrews University Library (project 229) (Records of the Scottish Cultural Resources Access Network (SCRAN), Edinburgh, Scotland).

St Enoch’s presence in Glasgow’s place names is a reminder of the city’s early Christian roots, and of the woman whose story helped shape its foundation.

The Glasgow Fair

And what of Bishop Jocelin? Well, today he’s barely remembered at all in the streets and place names of the great city that he helped to build. However, if you look closely at the streets around the west end of Glasgow Green, you’ll find Jocelyn Square, a forgotten and unassuming area behind the old High Court.

The Mclennan Arch was relocated several times during the 20th century. This image shows it in its location at the foot of Charlotte Street. Now at Saltmarket, you can find a plaque nearby that reads: “Jocelyn Gate. This area, formerly known as Jocelyn Square, was the site of both the famous Glasgow Fair and, until 1865 of public executions.” Image Crown Copyright: HES. Zoom in on trove.scot

However, in earlier times, Jocelyn Square held a more significant place in Glasgow’s history. It was the original location of the annual Glasgow Fair, a local holiday traditionally celebrated in the latter half of July. Known as the oldest event of its kind in Scotland, the fair dates back to the 12th century and its first recorded instance was in 1198, when Bishop Jocelin secured royal permission from King William the Lion to host the festivities.

Looking for more Glasgow stories?

Glasgow Cathedral collection

Every Glasgow Cathedral collection purchase helps us protect our historic places throughout Scotland. Shop for Glasgow Cathedral souvenirs on our shop.