When I first heard that I’d be heading to St Mary’s Church in Grandtully to help conserve its extraordinary painted ceiling, I was thrilled. Opportunities to work on something this rare and historic don’t come around often. As a trainee, it was a chance to gain some unique hands-on experience while contributing to the care of a truly special piece of Scotland’s heritage.

Grandtully Church is in a beautiful location. It’s quite secluded on a hillside in the rolling landscape of Perthshire. It’s a very peaceful place. There’s been a church in this spot since at least 1250, although the church that stands here today is probably a bit later, dating from around 1533.

You can really feel the age of the place when you visit. From the unassuming appearance of the outside of the church, you probably wouldn’t expect to find the impressive statement ceiling inside.

The ceiling is stunning. It was painted in the 1600s and is composed of a number of panels featuring coats of arms, saints, and proverbs.

The patron

The remarkable painted ceiling at St Mary’s Church owes its existence to Sir William Stewart of Grandtully. He’s a figure whose life was closely intertwined with the court of King James VI. Born into a prominent Highland family, Stewart was educated alongside the young king at Stirling Castle, forging a lifelong connection that would shape his career. By 1585, he was serving as a page of honour, and later became a gentleman of the king’s bedchamber. This was a role that placed him at the heart of royal affairs.

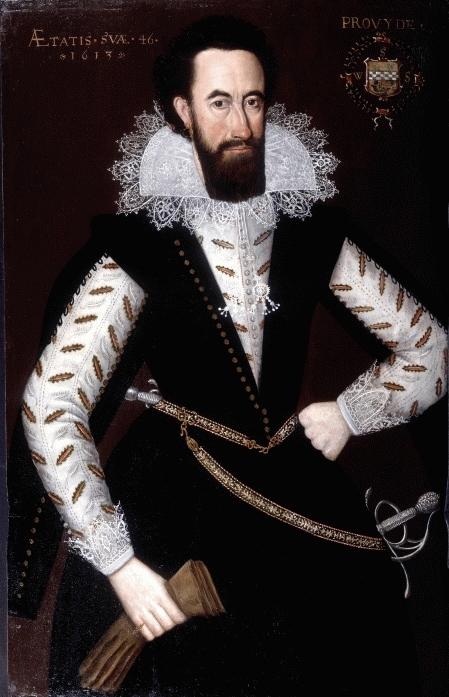

William Stewart of Grandtully, by Adam de Colone. Image credit: Wiki commons.

Stewart’s loyalty to James VI was more than ceremonial. He played a key role in the dramatic events of the Gowrie Conspiracy in 1600, helping to protect the king during the attempted abduction in Perth. In recognition of his service, James VI rewarded him with keepership of the forfeited Ruthven Castle of Trochrie and the office of bailie of the lands of Strathbran. Despite his close ties to the monarch, Stewart seems not to have followed the court to London after the Union of the Crowns, instead focusing on his estates in Perthshire.

Around 1636, Stewart and his wife Dame Agnes Moncrieff commissioned the painted ceiling at St Mary’s Church, extending the building and adorning it with vivid imagery and heraldry that reflected their status and taste. His portrait, painted by Adam de Colone, still hangs at Murthly Castle, another of his residences. He was laid to rest at Grandtully in 1646, most likely in the chapel itself, rather than in the graveyard.

The artist?

Sadly, we don’t have any clues to the identity of the artist or artists who created the impressive scenes at St Mary’s. Their identity feels like an important missing piece of the jigsaw. While we were working on the conservation of the paintings, clambering up and down scaffolds to work on the vaulted ceiling I often thought about the original artist, who would probably have been working in a similar way – although without the hard hat and floodlights!

Why it’s rare

The ceiling is one of only two of its kind in Scotland, the other being the Skelmorlie Aisle at Largs Old Kirk.

The elaborate monumental tomb and intricate painted ceiling of Skelmorlie Aisle.

Most decorative church interiors from before the Reformation were destroyed or stripped as Scotland shifted from Catholicism to Protestantism. The Reformation of 1560 led to widespread destruction of Catholic imagery. Religious images, statues, stained glass, and painted decorations were seen as idolatrous and were removed or defaced. Painted ceilings, which often featured saints, biblical scenes, and symbolic motifs, were especially vulnerable.

Interestingly, the ceiling at Grandtully St Mary’s was installed around 1636, when attitudes had slightly softened in some areas. Even so, it’s remarkable that such a richly decorated and symbolically dense ceiling was created and preserved during a time when religious art was still viewed with suspicion. This tells us a lot about the politics and religion of Sir William. Stewart was in favour of the reforms Charles I was attempting to bring in, which were to make the Scottish church more Anglican, and thus more similar to Catholic ideologies than the strict Presbyterian ones of the Reformers.

Doing the prep work

Before we head out on our missions to conserve historic paintings, we do a lot of research and preparation in advance.

St Mary’s Church was taken into care in 1944. At the time, the ceiling and roof were in poor condition, and they’ve since been treated repeatedly for insect damage and timber rot.

We survey the ceiling every 5 years, so there’s a lot of records and information about its condition and known problem areas. The most recent survey highlighted that it was, once again, time to visit Grandtully St Mary’s and deliver a bit of TLC.

The prep work involves lots of different aspects, from arranging a portaloo for the week as there aren’t any toilet facilities at the church, to packing a range of conservation adhesives for treatment of the ceiling.

We also work closely with colleagues in our Monument Conservation Unit who supplied us with mobile tower scaffolds and lighting for this project and also arranged the temporary closure for the week.

On site

Working on site itself is the highlight of my work as a conservator. It’s the moment that all the preparation has been working up to.

We work closely with our works teams, who do all the regular care and maintenance of our sites and have important expertise around things like building the scaffold platforms that we work on and supplying equipment like lighting and generators necessary for us to work in a site like Grandtully.

For us, it means being away from home for a week, so we need to make sure we pack all the specialist equipment we’re going to need in the course of the week.

Although the site was closed while we were working, we still had several visitors arrive to take a look at the ceiling, some from as far away as Australia! Although we couldn’t invite them in for a look while we were working, they were welcome to peek through the door and see what we were up to. Many were completely shocked (as was I!) at the difference between the unassuming exterior of the church, and the richly painted interior.

It’s quite an intense week as we keep ourselves busy moving and climbing the scaffold tower to reach all areas of the ceiling. A neck massage is much needed at the end of the week as much of the work is undertaken overhead!

Face to face with the ‘King of Terrors’

Its 28 roundels depict saints, proverbs, and heraldic emblems, all set against a background of fruit, flowers, and reclining angels. These elements are connected by ornate strapwork and arranged around a dramatic central panel showing the Resurrection and Last Judgement, complete with angels sounding trumpets and a skeletal “King of Terrors” striking down a dying figure.

This dramatic motif originally symbolised the inevitability of death and the Last Judgement. The skeleton, armed with a spear, represents mortality striking at the moment of death, while angels sound the final trumpet to summon souls. It’s a powerful reminder of faith, repentance, and the hope of resurrection, and similar imagery can be found on gravestones and devotional art from the same period.

Being up close on the scaffold, I could see the work of the original artist and the layers of restoration it’s undergone over the centuries. It felt like stepping into a conversation across time, connecting with the people who’ve cared for this ceiling before me.

My role was to help fix flaking paint and gently clean away loose dirt and debris. It’s delicate work, and working overhead certainly makes things more challenging! But with guidance from Ailsa, our experienced painting conservator, I learned how to approach this kind of surface with care and precision. It’s been a huge confidence boost and a real highlight of my year at HES.

An audience

What made this particular task even more memorable was having to work in front of an audience. On one of our days on site, colleagues from our corporate communications team joined us to film a Halloween-themed video inspired by one of the ceiling’s most striking images: the skeletal “King of Terrors” looming over a dying figure in the central panel.

The comms team saw an opportunity to use this vivid and eerie image to connect with audiences in a fun and seasonal way, while also showcasing the behind-the-scenes conservation work that goes into preserving Scotland’s historic sites. Suddenly, I wasn’t just a conservator, I also had to be a (somewhat reluctant!) actor.

Briege being filmed by Matt from the HES photography team.

Being filmed while working was definitely outside my comfort zone. It was more nerve-wracking than handling centuries-old paint, but I’m glad we did it. The video is a fun way to show the public the unusual and fascinating work that goes on behind the scenes at HES.

Conservation isn’t always glamorous, but it’s deeply rewarding. I feel incredibly lucky to have played a part in conserving this beautiful ceiling so future generations can continue to enjoy it. And who knows – maybe the Hallowe’en film will inspire someone else to explore the world of heritage conservation!

The silent D

The wee film we made plays with the common mispronunciation Grandtully. The name Grandtully comes from the Gaelic Garantulaich, which translates as the thicket or den of the knoll. You can find more information on the history of the place name on Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba (Gaelic Place-Names of Scotland).

Here, Calum Maclean, explains the changes to the place name over the centuries:

View this post on Instagram

Early records include the spelling ‘Carantuli’. Nowadays the name is usually pronounced ‘Grantly’. If you’re paying a visit, remember “It’s Grantly, not Grand tully!”

Visit the church

This winter, St Mary’s Church in Grandtully is open to visitors from 10am to 4pm every day. I hope everyone who steps inside takes a moment to look up and appreciate the artistry and care that’s gone into keeping this ceiling alive.