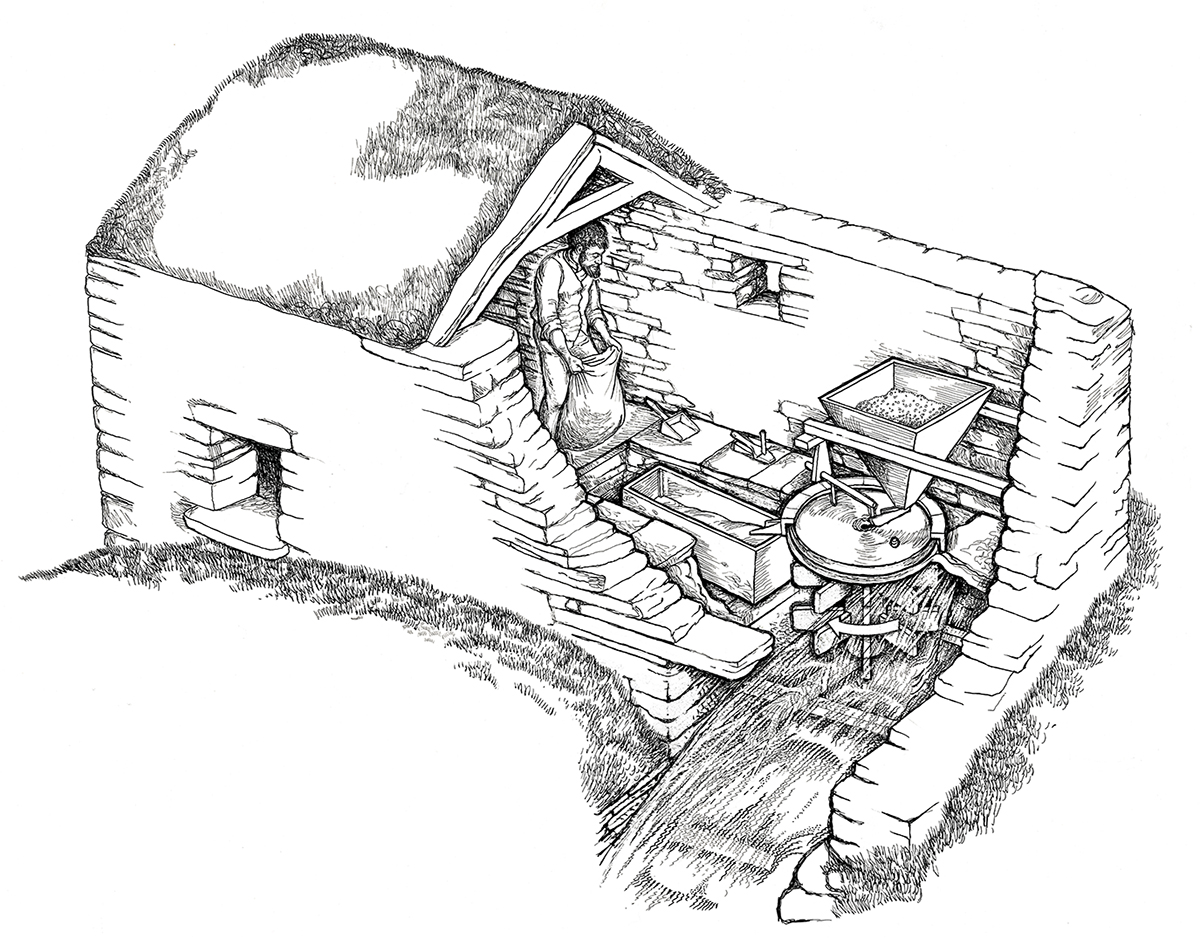

Illustration showing how the Earl’s Bu may have looked, by Alan R Braby

Dr Colleen Batey HonFSAScot has just published a book which challenges the narrative. She explains below in this guest blog.

The Narrative of the Orkneyinga Saga

As one of the jewels in the Norse archaeological record of Scotland, The Earl’s Bu and its adjacent Round Church (dedicated to St Nicholas) have been long considered part of a well-rehearsed and unchanged narrative.

The Round Church of St Nicholas at Orphir, by the Earl’s Bu. Photo by Colleen Batey.

Whilst the pages of the Orkneyinga Saga provide potential insight into the lives and power struggles of the Late Norse Earls of the Northern Isles and Caithness, it is the archaeology which provides the flesh on these bare bones – in some cases literally!

In the case of Orphir, the description of the site has been traditionally considered to be a record of the buildings and activities supplied by a reliable informant:

Earl Páll (Paul) had a great Christmas feast which he prepared at his estate at the place by the name of Orphir; he invited many noble men there….There was a very large estate and it stood on a slope, and there was a bank behind the buildings…

There in Orphir was a large drinking-hall, and there was a door at the eastern gable end, on the south- facing side wall, and a splendid church stood in front of the hall door and it was downhill to the church from the hall. And on going into the hall, there was a large upright slab to the left, and behind it were many large beer barrels, and opposite the entrance was a sitting room. (Jesch 2025, Chapter 66)

Some of this detail can be identified within the visible archaeological record: “a splendid church” although curiously not described by its most distinctive circular form, and large scale feasting in a “drinking hall”.

Several early antiquarian investigations sought to locate the large hall, from as long ago as the 18th century. It was however, the excavations in 1939 (directed by James Storer Clouston of nearby Smoogro, Orphir on behalf of W G Grant, the incoming landowner of the Bu who lived in Rousay) that focussed on uncovering the substantial stone walls which can today be seen in the grass-covered footprint.

Looking South to the Church. Photo by Colleen Batey.

There was no thought that these were other than the walls of the drinking hall of the saga. Minimal recovery of floor debris, the middens within the buildings or disposed of outside the doorways failed to impact on the drinking hall narrative. Material was doubtless found, but went essentially unrecorded.

looking north to the modern farm and lands beyond – the so-called “drinking hall” remains. Photo by Colleen Batey.

A similar narrative… but with key differences

The excavations in more recent decades, which took place just to the north of the Bu remains, revealed a horizontal mill (one where the water wheel lies horizontally) of Norse date.

Here the opportunity was taken to re-assess the initial interpretation of the “Drinking Hall”.

Identified within the Orkney Archives, the notebook of Storer Clouston has provided a partial record of detailed site plans. These indicate phasing and junctions of walls, some of which are not now visible on the surface, as well as several more stretches of walling further to the west.

These enable crucial re-interpretations to be made. The “Drinking Hall” walls indicate several buildings spanning a number of periods and not a single hall.

Critically, the much wider area of the Church and hall is filled with building footings no longer visible on the surface. It’s clear the Church lay at the heart of the Late Norse farm of the Earls, with buildings (dwellings, storehouses and barns, probably also kitchens) spreading in an arc northwards.

Inside a horizontal mill (this one is actually Click Mill)

Part of this expanded complex to the north included the remains of a Norse horizontal mill, the first of the date to be excavated fully in Scotland. The evidence from these excavations has transformed our understanding of the Norse complex at the Bu.

Located to the north of the recognised buildings, in the 1950s the farmer William Stevenson had discovered a stone-lined passageway resembling part of a souterrain. It was to this site that a group of archaeology students, then excavating at the Brough of Birsay under the direction of Chris Morris, came on a site visit to the Bu in 1978.

That was the start of the next phase of excavation at the Bu! Successive seasons of work uncovered that the souterrain was in fact a horizontal mill.

The mill today, looking west towards the underhouse. Photo by Colleen Batey.

Middens (both underlying the mill and infilling the collapsed underhouse) have added colour to our understanding and in many cases changed our perception of what was happening at the Bu in the days of the Earls.

Timeline of the Earl’s Bu

Before the mill was constructed, the locality had both Neolithic and Bronze Age presence as would be anticipated in such a good location. After all, this is an area of gradual sloping land with flowing water courses, with a southern aspect and access to Scapa Flow.

There followed a Late Viking farmstead, probably dating from the days of established Scandinavian presence, circa late 800s to mid 1000s AD. This evidence is in the form of material dumped from a nearby farm, which created a substantial mound (into which the mill was subsequently built). Within the debris, unique insights of life in Norse Orkney at that time have come to light.

A major component of the investigation focussed of the recovery of the environmental data, the debris of everyday life found in the remains of animal bones and fish bones.

Of considerable interest here is the identification of the Thorrablot feasting tradition – mid winter feasting on animal parts not conventionally part of the menu, most particularly head meat – and on a substantial scale.

Although common in modern day Iceland, the archaeological recovery of this debris in the British Isles remains unique. I’d highlight the work of Ingrid Mainland on all aspects of the ecofactual material (organic evidence found at archaeological sites such as seeds, pollen or bone) here. These results and those of her colleagues across all periods have been transformative in our interpretation.

Aspects of the artefactual material from this pre Mill phase are interesting too.

Gold working was identified on site, similar to some assembled at the Brough of Birsay. The combination of a silver ring money fragment, two weights of East Scandinavian/Baltic origin and in the Arabic weighing system, plus a steatite ingot mould for forming silver into bars, all indicate a bullion (non-coin using) economy.

We also see the carving of runic inscriptions on animal bones in this period, with the form indicating an earlier date for this literacy than found at Maeshowe!

Runes carved into the wall at Maeshowe Chambered Cairn

Finally, within these Late Viking middens, several pieces of steatite cooking vessel fragments were recovered, representing sources in both Shetland and Norway. These aspects indicate far reaching contacts, a network of trade and commercial exchange in the Northern Isles in the 10-11th century.

The Norse Horizontal Mill

The building of the mill began somewhere around 1050 AD, the potential (fluid) cross over period between the Late Viking and Late Norse eras.

The structure itself was dug into the huge farm mound created in the Late Viking period. When viewing the site today from the East, you can see a notable rise in the land towards the Round Church.

The mill had a short life with a number of alterations and was powered by a redirected stream from the north. The processing of barley and oats is demonstrated.

The manpower for working the mill and supplying the crops suggests the Late Norse Earls at the Bu likely had unrestricted access to the immediate locality, for both labour as well as land. Clearly this Estate land played a crucial role in the resource base.

The working life of the mill was short-lived, probably in the region of 25- 50 years or less. As it fell out of use, the mill building itself was dismantled, leaving only a large hole in the ground where the water wheel had lain.

The next stage of midden dumping provides us with the link to the “Drinking Hall” complex to the south.

The Feasting Continues…

The extensive dumping activity, once the mill was abandoned, provides the narrative previously missing from the Storer Clouston excavations.

Rapid infill of the Underhouse followed periods of extensive feasting at the home of the Earls. The selection of choice joints of meat – beef, port and lamb, were supplemented by both dried and fresh fish, cod and haddock as well as salmon and trout.

Scientific study indicates local resources being exploited, although of course the Earls could exact tribute of food from anywhere they chose. Fish from Westray and grain from Sanday would be obvious choices.

The profile of the feasting debris in this later stage of the site differs notably from the pre mill feasts.

The role of feasting in a political narrative is well documented, and seen even today in a modern context. The Late Norse Earls were no strangers to the notion of diplomacy around the dinner table.

It seems from the evidence at the Earl’s Bu that seasonal feasting was de rigeur. This was potentially associated with local legal gatherings for the Thing as well as harvest and Christmas gatherings (which are commonly cited in the Saga, as we’ve already seen).

A Thing (from the Old Norse þing) is a word for an assembly place. Many of these had already been identified in Orkney – Tingwall would be the most obvious.

The Earl’s Bu – Set within its own Estate

The possibility of identifying the local Earls estate arose when a Thing site placename was identified nearby (Rareting).

We can also see named features derived from Old Norse terms. The Hubbin (Old Norse derivation for harbour) lies close to the Earl’s Bu. Some local farm names come from Old Norse too – for instance Grindally comes from a gateway in a bank or boundary.

This boundary encloses the farmland, defining it from the outlying rough grazing, and it defines the natural basin enclosing the arc of farms to the north of the Bu.

This is identified with the bank described in the description cited above. Bringing these elements together with the Orkneyinga Saga and many farm names/locations recorded in the 1492 Rentals for the area, it is now clear that the current visual focus of the site around the Church and grass footings can be seen not as one drinking hall, but more accurately as the heart of a substantial complex.

We can now take huge strides beyond the Bu, into a landscape populated by tenant farmers and attendants to the Earls; a far cry from the limitations of those grass covered walls of the fragmentary small buildings next to the beautiful Round Church.

Remains of the magnificent circular church dedicated to St Nicholas beside the Earl’s Bu

This is a story which began with the Orkneyinga Saga, now amplified and expanded with scientific discoveries within a landscape largely named by those same Norse speakers. But this will not be the end of the story for certain…

If you’d like to learn more, we’ve been working with Colleen Batey to publish a new book: The Earl’s Bu, Orphir – Feasting, Farming and Commerce at the Heart of the Orkney Norse Earldom.