The impact of climate change on archaeological and historic sites is increasingly becoming a source of concern in the cultural heritage sector. The Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site is currently at risk from a range of environmental, climate-related factors, such as increased storminess and sea level rise, which contribute to higher rates of coastal erosion. This is particularly true at Skara Brae, which is possibly one of Scotland’s most vulnerable historic sites.

Panoramic view of the Bay of Skaill (26 Apr 2016).

Skara Brae is a Neolithic settlement situated on the Bay of Skaill, on the West coast of Orkney. The excavated area includes a number of remarkably well-preserved houses with a variety of stone furniture and other artefacts. The discovery of the site was the result of storm activity, originally in 1850 and subsequently in 1924. Interestingly, Skara Brae was not originally a coastal site. Its very discovery was a consequence of coastal erosion, and that same phenomenon is now placing the site under threat.

Digital documentation of the Orkney World Heritage Site, including Skara Brae, was carried out in August 2010 for the Scottish Ten project, resulting in high-resolution, accurate 3D digital models of the sites. These can be used in various ways to help with heritage interpretation, but also for the conservation and management of the sites. In Skara Brae, 3D point cloud data from laser scanning is being used to monitor the degree of coastal erosion on the Bay of Skaill, which could potentially have a massive impact on the long-term survival of the Neolithic village.

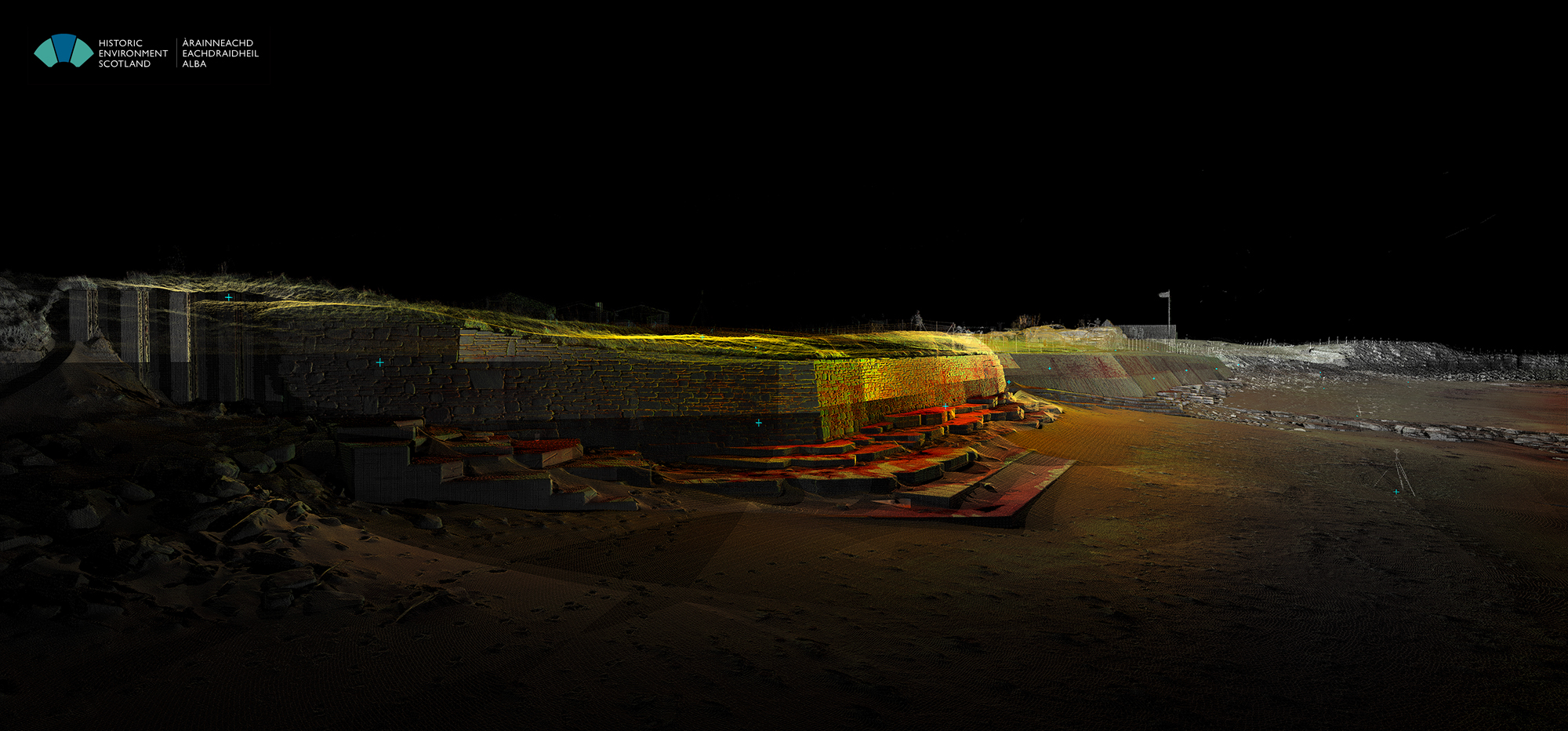

Point cloud image from the NE end of the sea wall, looking along the beach towards the West.

The protective sea wall

The vulnerability of Skara Brae to serious storm damage was recognised very early on. The sea wall, erected in the late 1920s and strengthened several times since then, is designed to take the brunt of any storm action, thus protecting the vulnerable archaeological remains. The wall has been successful so far, but more frequent or more violent storms could change that. It is important to note that, while the wall protects the excavated part of the Neolithic village, it does little to protect the rest of the coastline. To the contrary, it is possible that the presence of the wall may cause increased erosion to the ‘soft’ landscape of the sand dunes on either side of it.

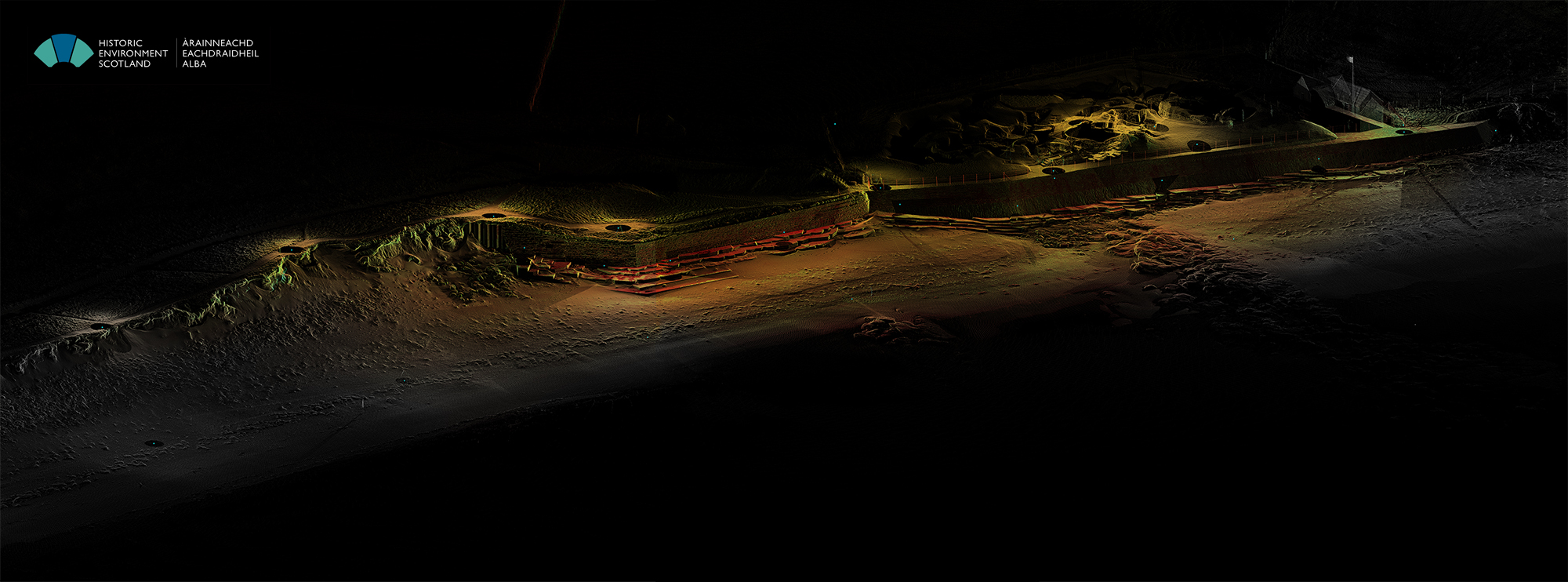

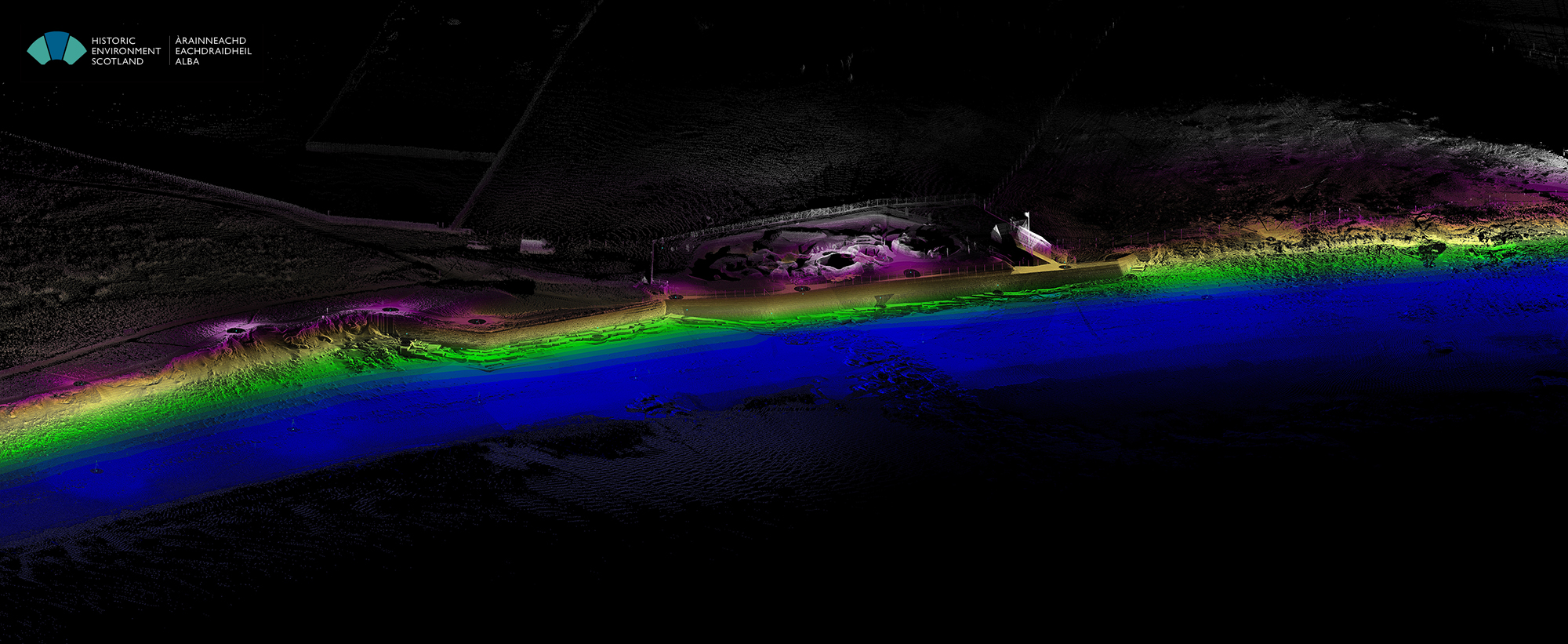

General view of the point cloud at Skara Brae from the NE, showing the protective sea wall and sand dunes to either side of it. The Neolithic village is visible at the top right part of the image.

Skara Brae and the Bay of Skaill present a dynamic system of natural and man-made elements, balancing under constant threat from an ever-changing environment. The presence of nearby unexcavated and, in many cases, completely unknown archaeology similar to Skara Brae must also be taken into consideration. Careful monitoring, not only of the archaeological site but also its context, is essential in ensuring the continued protection of Orkney’s unique heritage.

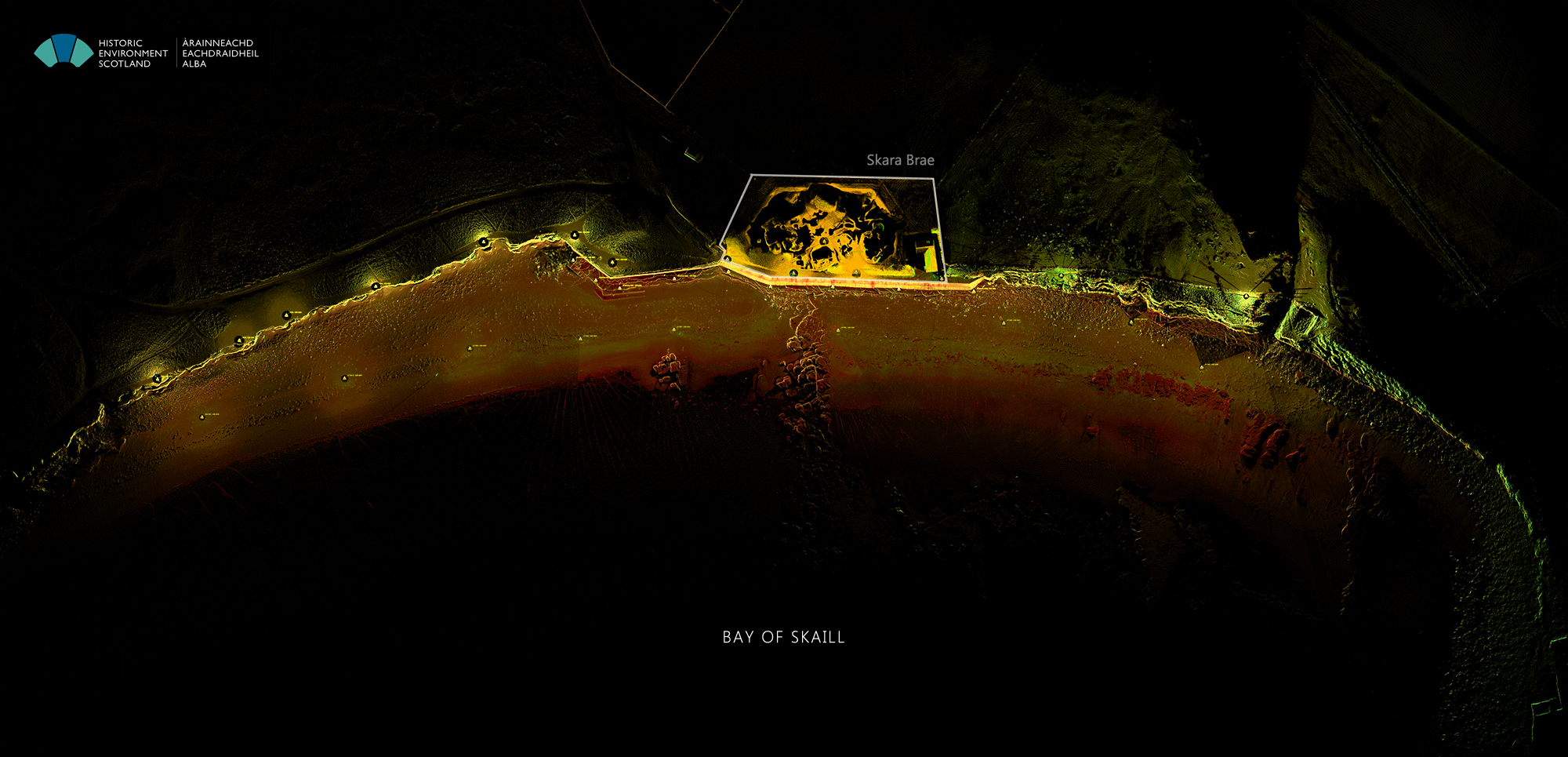

Plan view of the point cloud showing the Bay of Skaill. The outline of the Neolithic village is marked on the plan and the wall highlighted with brighter colours

Coastal erosion monitoring

Coastal erosion monitoring at the Bay of Skaill is the purpose of our continued visits to Skara Brae since 2012. In April 2016, the Digital Documentation team, together with colleagues from the Conservation North office, worked on site for 2 days, collecting data along the beach, at the top of the sea wall, and along the dunes to the East of the village. Two different laser scanners were used as our primary survey instruments (Leica C10 and P40). Laser scanners are line-of-sight instruments, i.e. they can only capture what is in their field of view. Depending on the topology of the site, several scan positions must be utilised to get a complete picture of the targeted areas. In this case, data from 34 different locations were collected, some over Permanent Survey Markers. GNSS data will allow us to georeference the survey.

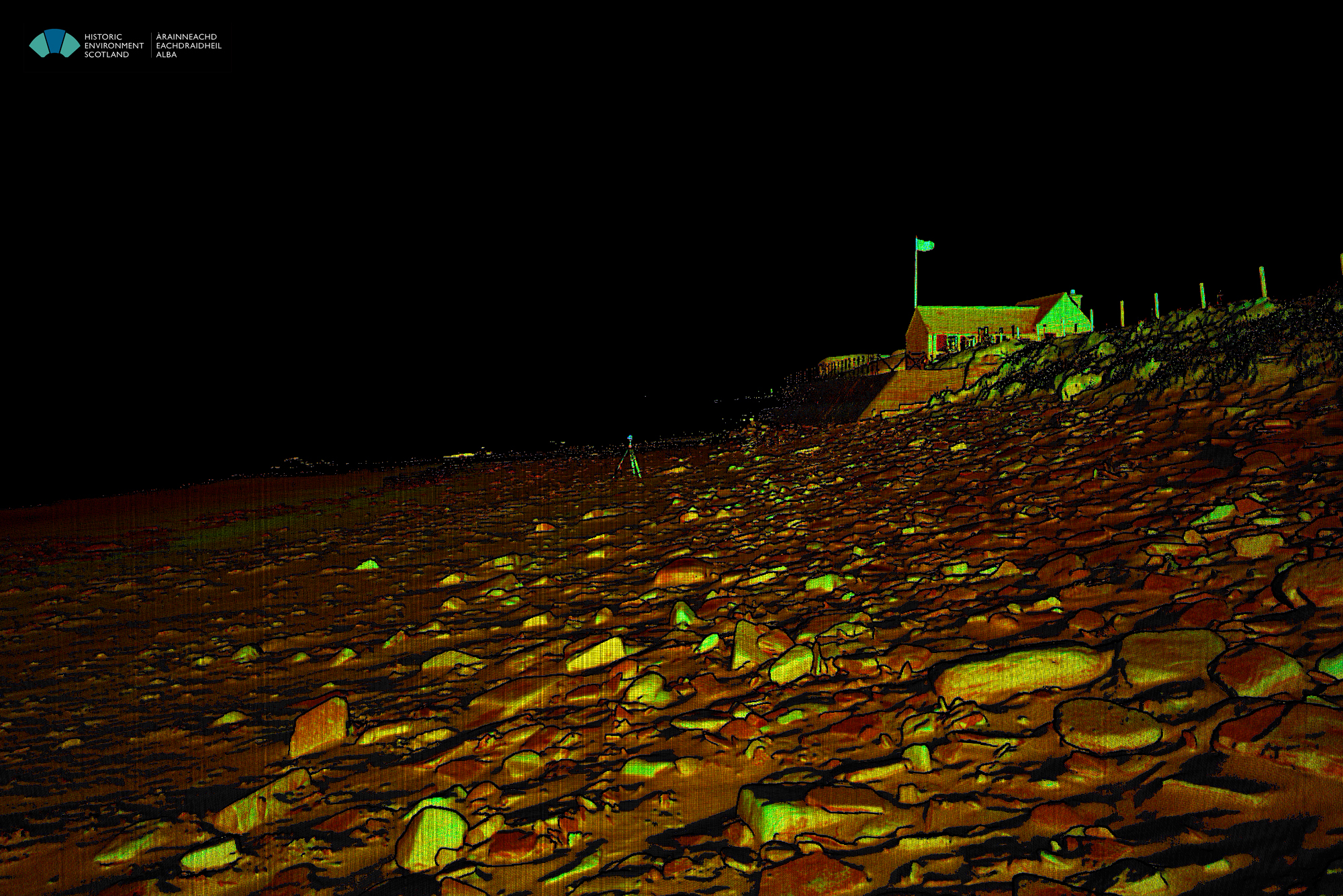

View of a single P40 scan from the beach, SW of the village. The small visitors’ hut is visible on the top right corner of the image.

The data is currently being processed, but here is a preliminary image:

View of the point cloud from the NE, coloured by elevation: blue for the lowest points and white for the highest.

Of course, a single 3D point cloud of the site, no matter how accurate or complete, cannot reveal the effects of coastal erosion (changes in the coastline and sand dunes) until it is compared to similar datasets recorded at different times. That comparison is the final step of our project and creates our 4D dataset, i.e. 3D data measured at different times. Our 2016 point cloud will be compared to the 2014 dataset, to reveal changes in the coastline that have occurred over that 2-year period. It will also be compared with the 2012 or the 2010 dataset, which forms our baseline survey.

Coastal erosion monitoring at Skara Brae is part of the RAE Project, aiming to digitally document in 3D all of the properties in the care of Historic Environment Scotland. The Skara Brae coastal monitoring programme is a pioneering project that could also be applied for other coastal sites in the HES estate that are currently under threat from coastal erosion, sea-level rise and increased storm activity. This programme is however only one part of Historic Environment Scotland’s strategy for managing coastal change. For more information, see Dynamic Coasts and the Historic Environment.

For more information about the work of the Digital Documentation team, follow them on Twitter @ScottishTen or look for #RaeProject to find out more about the Rae Project.