Written by Georgie Ritchie and Adrian Cox

As Georgie is the latest recruit to the Cultural Resources Team, a trip to Lochmaben Castle provided the perfect introduction to the work of our department, framed within the wider remit of HES as a whole.

In a nutshell, the Cultural Resources Team are tasked with developing knowledge and understanding of our over 300 Properties in Care, right across Scotland. This information then feeds into broader decisions about the conservation, management and presentation of the sites, and creates many opportunities for collaborating with other departments.

We have recently been working in partnership with the Castle Loch Lochmaben Community Trust (CLLCT), who have taken ownership of the loch and the area surrounding the castle, on proposals to raise public awareness of the castle both locally and further afield. Last month, we commissioned an archaeological geophysical survey in order to find out more about the nature of Lochmaben’s occupation and development over the centuries.

This new archaeological research offered an ideal opportunity for us to engage the enthusiasm expressed by the local community and hopefully fill some of the knowledge gaps of the site.

A quick history lesson

Aerial view of Lochmaben Castle

At the heart of the castle site are the upstanding masonry remains of a 14th-century fortress. Beyond this lies an extensive area of earthworks, forming an important medieval defensive complex. Although limited excavation took place at the site in 1968-72, its archaeological remains are not well understood.

The site has links with the de Brus (Bruce) family, who were granted the lordship of Annandale by David I in 1124. Occupying a key strategic position, the castle was involved in cross-border conflict throughout the Wars of Independence, changing hands several times. Stone buildings are first recorded at the site in 1364 and it is possible that the castle’s unusual south-facing frontal wall was built by the English around this time.

Following its capture by Archibald Douglas in 1385 and the subsequent overthrow of the Douglas family, Lochmaben became a royal castle and has links to James IV, who constructed a great hall here in 1505. James V also used the castle as a campaigning base, and Mary Queen of Scots and Lord Darnley hosted a banquet here in 1565.

Lord Darnley and Mary Queen of Scots

After a long and colourful history, the castle’s function became obsolete following the Union of the Crowns in 1603, and its stone facing was almost entirely removed to provide building stone for the growing burgh of Lochmaben.

A challenging castle

The loss of the castle’s facing stone has led to a variety of conservation challenges since it was taken into state care in 1939. Its once finely dressed ashlar masonry has been robbed out over succeeding centuries, in some areas leaving behind little more than a picturesque ruinous wall core.

The challenge therefore lies in making this a readable structure, in helping the visitor relate the shell of a building before them to the grand structure as it once stood – and here the power of the reconstruction drawing truly comes into its own.

The Interpretation Unit regularly commission artists’ reconstructions to help portray a vision of our properties as they once were, based on our current understanding. Depending on the type of site in question, this might be informed by historical accounts, archaeological excavations, other known contemporary examples, or occasionally even experimental archaeology. They are then able to produce an interpretive visualisation of the structure as it may have looked at a particular time, and therefore aid a visitor’s understanding; in this case, of the grandeur that once was.

Such visual aids can be particularly important in helping our visitors to engage with a site that has limited physical access. Parts of Lochmaben Castle are currently inaccessible, to protect the fragile walls and visitors alike.

But conservation of a structure like this is not a simple process. The open wall heads and exposed core are vulnerable to water penetration, with a risk of mortar being washed out and potentially destabilising the structure. Various attempts have been made to stop this process since the site came into state care, and for us, a particularly interesting aspect of the castle as it now stands, is this recent history of its management.

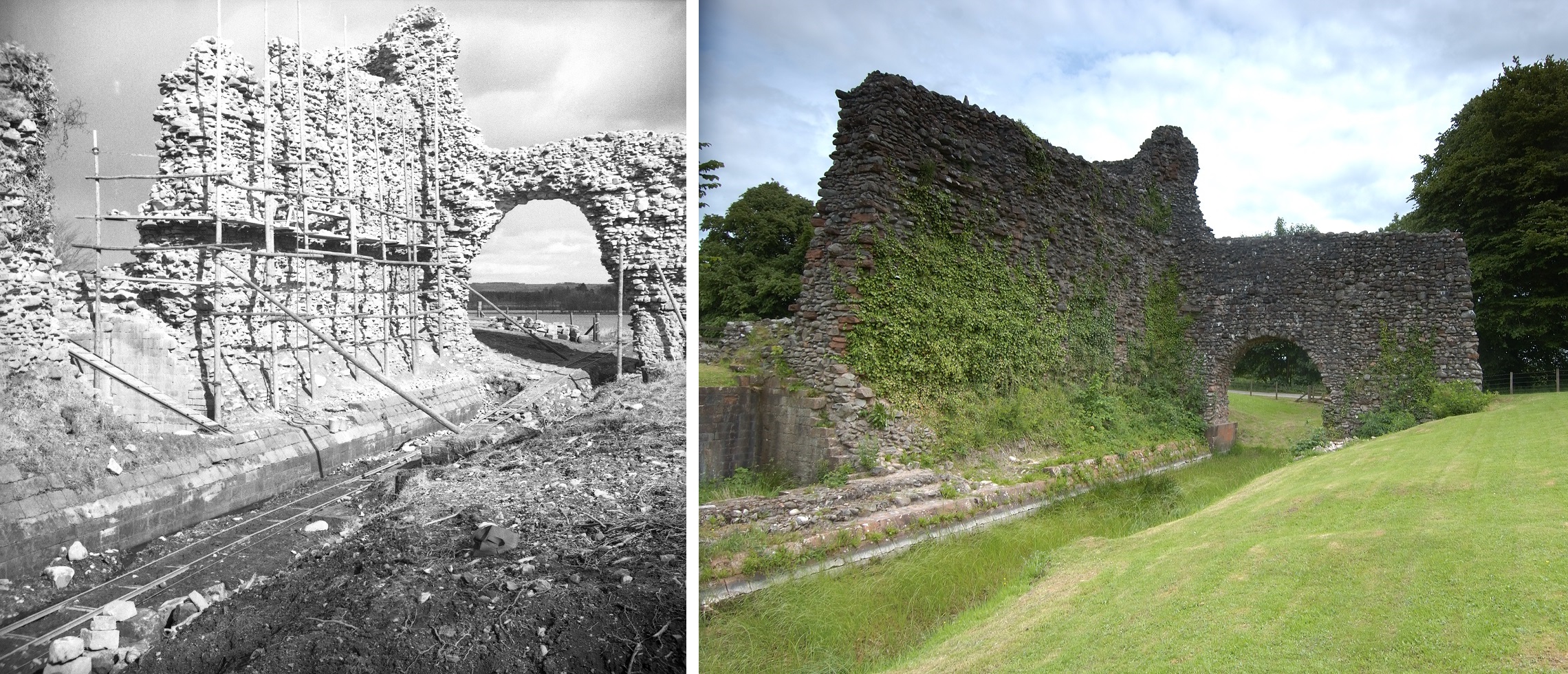

Lochmaben Castle in 1952 and now

A keen eye can spot the visible signs of modern intervention, through which we can also trace changing approaches to monument conservation. The areas of cement pointing and rough racking by our predecessors, or pockets of rebuild and tidying by our Victorian counterparts are approaches which we would not now adopt, but which were informed by the guidance and best practice of their era.

This poses a deeper philosophical question – whether to pick apart those earlier interventions which could potentially threaten the structural integrity of the monument, or leave them to be read as part of the latest history of the site?

Our best approach in considering the ongoing management of this and indeed any site, is to ensure we are as well informed as possible.

Archaeological survey

Resistance survey in progress on the peel area

Last month’s geophysical survey work was carried out for HES by our contractor, Rose Geophysics. The survey focused both within the masonry castle and on the surrounding areas, including the area of the peel, and was designed to address a series of research questions.

The community trust had greatly assisted us by clearing the vegetation from the peel area. Three different geophysical survey techniques (resistance, gradiometry and ground-penetrating radar) were used in combination, in order to achieve the best results.

Working closely with the geophysics team, we led outreach activities for the local community and visitors to the site. In collaboration with the CLLCT, we delivered two public events at which we presented talks and detailed guided tours on the history and archaeology of the castle and explained the current research, as well as giving hands-on demonstrations of the geophysical survey equipment. The two sessions were very well attended (with 75 people taking part) and altogether we spoke to over 240 visitors about the castle and the current research project. Adrian was very enthused by the positive responses we received from local community and visitors alike.

Adrian Cox leading a tour of the castle for the community

Our initial survey results suggest some interesting variations in the data collected across the site. Once processing is completed, these results will help us to target areas for further archaeological study. Hopefully this will fulfill further the strong community enthusiasm and engagement for this important monument.

There are many exciting projects and proposals afoot! But for now, Lochmaben Castle sits as a shadow of her former self, waiting to give up her secrets.

Adrian is an archaeologist in the Cultural and Natural Resources Team. He advises on archaeological matters at our properties in care and leads on the team’s outreach activities.

Georgie is an Assistant Cultural Resources Advisor, providing historical and archaeological research services related to our Properties in Care.