You might not think it, but as a PhD candidate in archaeology I spend the majority of my time in the lab using scientific techniques to uncover the past.

I might be demineralising bone samples, sitting at the computer analysing data, or attempting to absorb knowledge from a variety of written sources.

Admittedly this sounds less exciting than running from a giant boulder in a Peruvian temple. But let’s face it, the days of Heinrich Schliemann and an Indiana Jonesian archaeology have long passed!

Post-excavation research is an invaluable part of modern archaeology. The varied nature of this work has helped us develop all sorts of scientific techniques and sub-disciplines. For instance, I come from a bioarchaeological background, and as part of my doctoral study I research a seemingly small aspect of human life: diet.

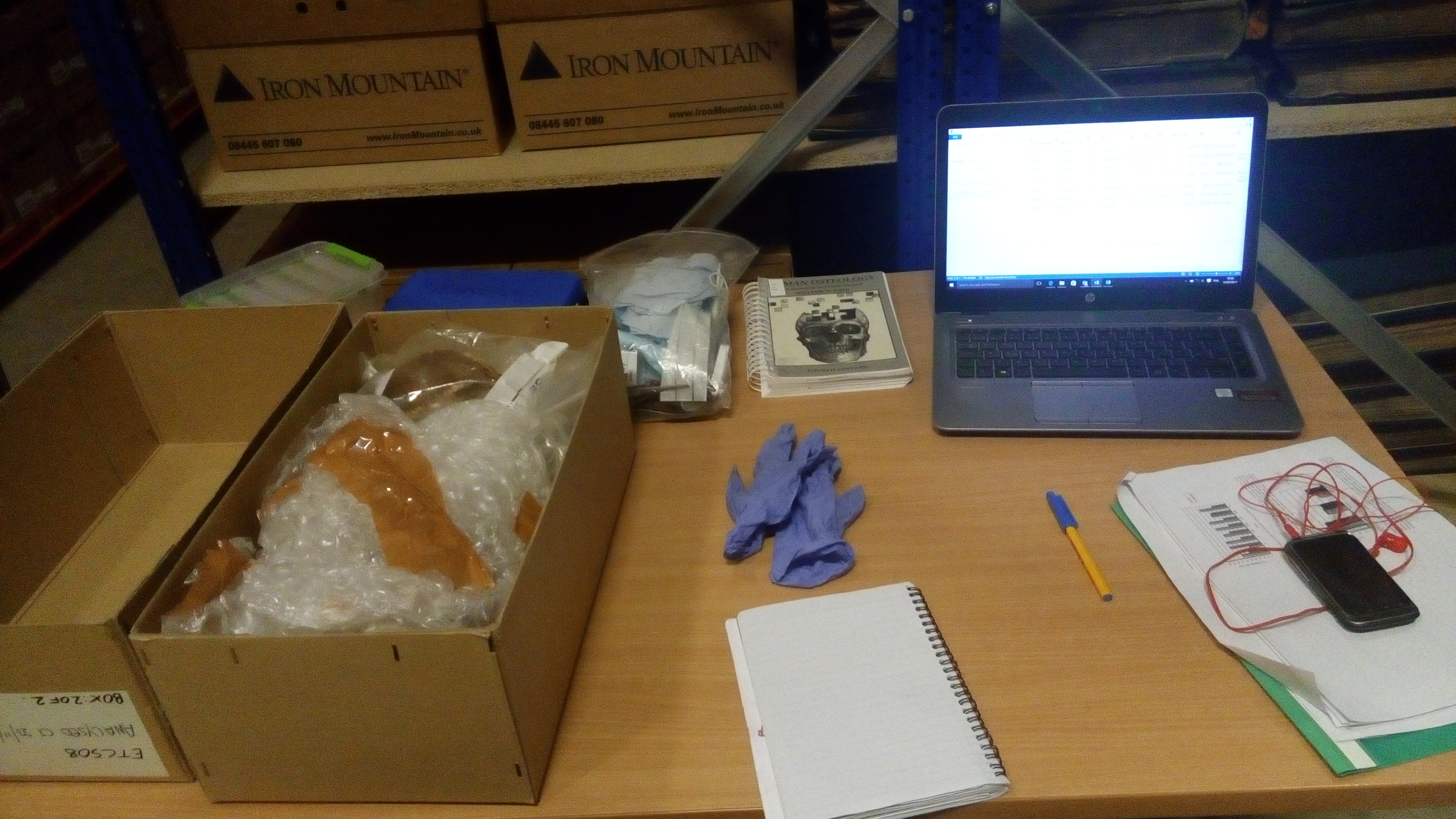

Looking through excavated materials and taking samples

The archaeology of food

Food is an important part of our lives. It’s not only necessary for our survival, it represents a fundamental cultural component.

The diet of a population can reflect identity, social and economic status and even cross-cultural contact. When we’re talking about food culture, we must consider the ways meals are produced, distributed and consumed.

We can even see the effects of developing trade networks reflected in people’s diet. It tells us about differences within and amongst populations, lets us follow the introduction of new foods into various geographical regions, and helps us see ideological or political influences.

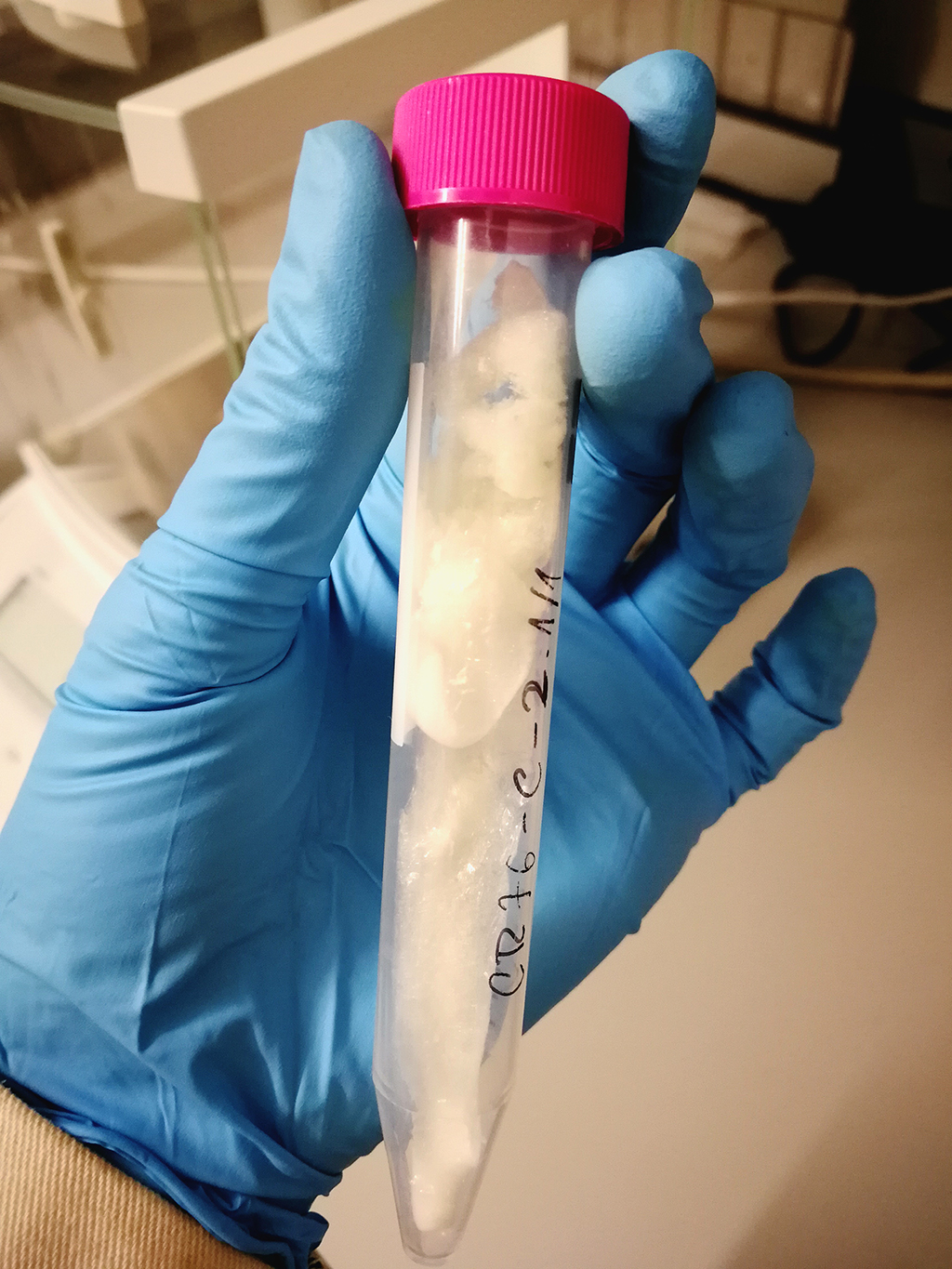

To detect dietary patterns, we use stable isotope analytical techniques on samples of human (as well as animal) bones and teeth.

Reconstructing past life-histories

It has been over 35 years since some of the earliest stable isotope analytical research of archaeological remains were published. These aimed to reconstruct the past diet of peoples in Europe and the Americas. Since then, this technique has become widely used.

Building on the principle that food and water consumed during one’s life leaves chemical traces in the body, it’s possible to identify signatures from food in bones, teeth, hair and finger nails. In my research I focus on two isotopes in particular, carbon and nitrogen. You can find these in preserved collagen, a protein found in bone and dentine (a major component of teeth).

I spend much of my time in our laboratory at the Department of Archaeology, at the University of Aberdeen extracting collagen from bone samples I’ve collected from sites around Scotland.

We analyse the collagen using an isotope-ratio mass spectrometer at the Scottish Universities Research Centre (SUERC). The data produced gives us a general picture of an individual’s diet over the last few decades of their life.

This type of data can tell us if someone relied on largely terrestrial or marine foodstuff, and their position in the food chain. Eating habits often tell us about social status, too.

Scottish food stories

As a doctoral candidate funded partially by HES, I have the opportunity to research dietary change in Scotland from the late Iron Age to the late medieval times. There are lots of interesting stories here, from Pictish burials through the arrival of Christianity, to the developing burghs.

The impact social and political changes have on local diet is often quite stark. One of the major case studies I’m working on is the effect of expanding trade networks and increased mobility.

My research focuses on the developing urban centres from Edinburgh, through Perth to Aberdeen. Because this is a large scale study, I depend on museums, fellow archaeologists and city councils to help me access a wide range of material. This helps me detect geographic and temporal patterns through time.

Storehouse full of artefacts

I’ve also been collecting samples from various storehouses, museums and excavations and will receive some data soon – exciting!

My funding will allow me to analyse over 700 samples at SUERC. I’ll also bring in already published data to enhance my research, making this study the largest of its kind in Scotland.

Finally, I plan to visualise my findings by creating time-aware maps showing changes in diet through space and time.

Concluding thoughts

Building on my own experience, I can confidently say there are great opportunities in archaeology for the scientifically minded.

Thanks to PhD student Orsolya Czére for this post. Publishing her findings and making them accessible is her ultimate goal, so stay tuned for her food stories of the past!