The God’s Eye View

The clear skies that had been forecast had still not arrived. Massed cloudbanks were shifting slowly westwards, the landscapes beneath blurred here and there by columns of rain.

It was morning and the sun was rising behind us, making rainbows flicker on and off all around us. Water droplets coursed over the helicopter’s windscreen. We dodged between the clouds. Drifting beneath us, part obscured and part framed by mist, was the city. Glasgow.

View through helicopter windscreen looking east over central Glasgow. © James Crawford

We had followed the course of the motorway in from the east, its thick grey line drawing the eye irresistibly onwards. We passed over the cathedral, once the heart of Glasgow, now a peripheral figure, pressed between a hulking Victorian hospital and a sprawling Victorian graveyard.

Then we were above the interlocking square blocks of the modern centre. Flying very slowly now, we were able to look down on the ordered grid of buildings and peer into the long, dark canyons of George Street, St Vincent Street, Ingram Street and Argyle Street.

George Square and Central Glasgow, 1927

George Square and Central Glasgow, 2015

The City of the Future

The sun emerged, striking the white faces of tower blocks and producing a powerful glare. For an instant they seemed lit up like beacons, signalling to each other from across Glasgow – from Townhead to Maryhill; from Maryhill to Anniesland; from Anniesland south over the river to Cardonald.

But we were on the hunt for a much older tower. Scotland’s first ever skyscraper.

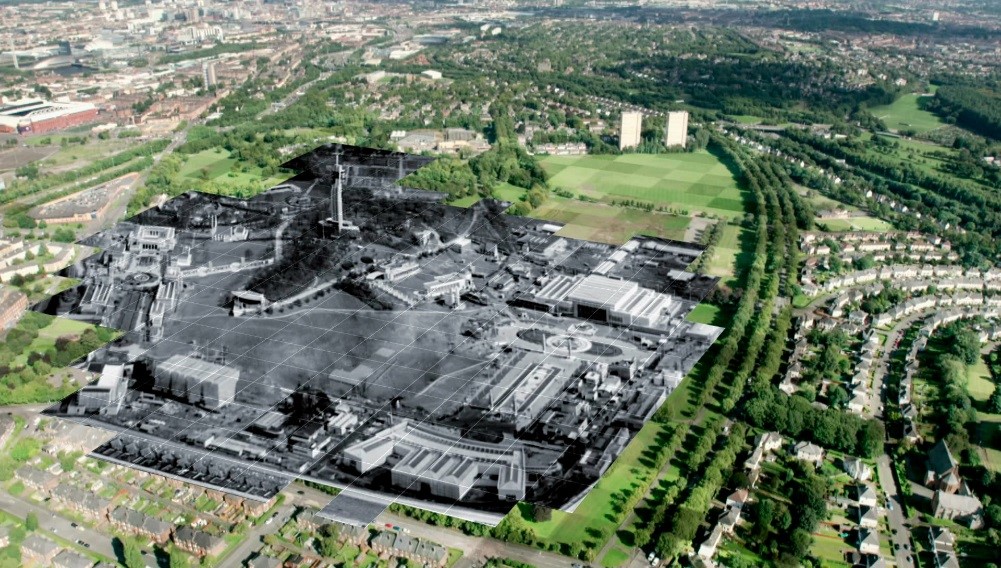

Now we were hovering over Bellahouston Park. Exactly 80 years ago, 170 acres of its wide open green spaces were transformed into a whole new mini-city, a city of the future, built from scratch in just 14 months.

Photo of Bellahouston Park in 1938 mapped onto a modern view from the helicopter

Between May and October 1938, the park was covered with custom built walkways, ornamental lakes, fountains, cafes, restaurants and bandstands.

Huge palaces were dedicated to all aspects of manufacturing – displays of everything from ships, steam engines and cranes to sewing machines, carpets, furniture, fabrics, knitwear and pottery.

It was called the ‘Empire Exhibition’ and over six months it invited a staggering twelve and a half million people through its gates.

Scotland’s First Skyscraper

The astonishing centrepiece of the exhibition was visible from almost anywhere in the city – a 300-foot-tall, pencil thin, aluminium clad skyscraper – dubbed the ‘Tower of Empire’.

The three balconies at its summit were capable of taking up to six hundred visitors at any one time, and from the top views stretched out some eighty miles in every direction. Here was a startling symbol of a new Scotland, raised up to look down on the old one.

‘The Tower of Empire’ in 1938. Over a million people travelled to the top of this tower using its two express elevators.

Glasgow’s Lord Provost hailed the Tower and the exhibition as showing ‘a finer and more colourful way of living’, a future ‘without drabness and greyness’. But when the gates finally closed at midnight on 29 October 1938, almost everything was dismantled.

The tower was built to last – designed to be a new icon of the modern Glasgow skyline. But within a year it too was demolished, out of fear that its great height would attract German bombers. Today, even its foundations are overgrown by the trees on Ibrox Hill.

The city of the future was gone. But not forgotten, and not for good.

‘Scotland must plan, or disintegrate’

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the world was in desperate need of planners. Scotland’s cities were seen as things of the past, ill-equipped to deal with the demands of the present, let alone the future. As the architect John Wilson put it, ‘Scotland must plan or disintegrate’.

There was an urgent need to look at the country in its entirety, assess every inch of land. The best way to do it was from the air.

In 1944, even before the war had ended, a handful of RAF squadrons were tasked with making a complete photographic map of all of Scotland.

They carried on for 6 years, making over 500 flights and taking nearly 300,000 photographs of Scotland.

Central Glasgow, photographed in 1947 as part of the RAF survey of all of Scotland

Their work took planners into the sky. Mosaic maps were made from stitched together photographs. Each one-metre-square mosaic was the same as twenty-five square kilometres of real land.

What could be laid on top was the blueprint of a post-war nation. The vision for a new Scotland was rising up out of these photographs. But there was still the question of what it would actually look like….

James underneath the Kingston Bridge – explaining how the view from above would go on to be used to plan Britain’s first urban motorway

The Kingston Bridge under construction, 1968

Our book based on the series is available now from all good bookshops and the HES online shop.