It’s not very often that you get the chance to travel back in time.

Through the doors of the aircraft hangar, waiting on the grass beside an apron of runway, was a 1942 DH82a de Havilland Tiger Moth – an open cockpit tandem biplane made of steel tubing, thin plywood and stretched fabric. This was going to be my time machine.

James Crawford and pilot William Mackaness walking across the runway of Perth Airport towards the waiting Tiger Moth.

I walked out from the hangar and across the runway with my pilot, William Mackaness. Together, we were aiming to recreate a pioneering flight made from this same Perthshire aerodrome in the summer of 1939. Back then the pilot was a man called Geoffrey Alington, who operated a company called Air Touring. And his passenger was Osbert Guy Stanhope Crawford – now dubbed the ‘father of aerial archaeology’.

The air was almost perfectly still – the aerodrome’s windsock was hanging listlessly from its pole. Beyond, to the north, you could see a wide expanse of farmland and the solid outline of the Cairngorms. The late summer sun was dropping, catching the distant mountains half in light and half in shadow.

The ‘time machine’ – the vintage Tiger Moth ‘Victor Tango’ waits on the grass beside the runway.

As I fastened the seatbelt straps over my shoulders and around my waist, William began to ‘tickle’ the engine – first allowing the fuel to flow down to the intake manifold, then drawing it into the engine itself by turning the large single propeller on the nose.

‘Magnetos off, fuel is on, throttle closed, four blades’, William recited. ‘Four blades’ referred to turning the propeller four times, to ensure that each cylinder takes in the fuel air mixture. Then it was ‘magnetos on’ – creating the electric spark that ignites the engine. With a guttural roar, the propeller in front of me spun to a blur.

The take-off was remarkably quick. William ramped the engine up to 1600rpm with the breaks still on. Then he gently released the breaks and fed in the throttle, which he controlled with his feet. ‘You need soft shoes for it’ he told me, ‘you have to feel the aircraft, and the power, right in the soles of your feet’.

Within seconds we were racing over the tarmac. I pulled the goggles down from my canvas flying helmet as the rush of air tore at my eyes. Another few seconds later, we were up. And we were going back in time.

Following in the flight path of OGS Crawford over the Strathearn valley.

From bicycle to aircraft

Osbert Guy Stanhope Crawford – OGS for short – was born in Bombay in 1886, but he grew up in Hampshire. As a schoolboy he roamed the many ancient monuments littering the chalkways of the Marlborough Downs, cultivating a lifelong passion for archaeology. The grandson of a Fife clergyman, at the age of 28 he donned a kilt to fight for the London Scottish regiment in the First World War.

After several months in the trenches he was offered a job as a Maps Officer, walking the Western Front to take panoramic photographs of the landscape. But as more and more aerial imagery came across his desk for map-making, he was determined to take his camera into the skies, and volunteered as an Observer for the Royal Flying Corps.

After the war, it was almost inevitable that he would combine his two great passions of flight and archaeology. He corresponded with the Ordnance Survey so incessantly about the inaccuracies – and absences – of ancient sites on their maps, that they created the new position of Archaeology Officer especially for him.

OGS Crawford poses with his bicycle

To begin with he was more of a cycling archaeologist than an aerial one. Throughout the 1930s he travelled to Scotland, urging his bicycle up and down back-roads and country lanes. But he always wanted more – to see more, to explore more, to look harder and look further. So in the summer of 1939 he requested permission to track down possible new Roman sites in Scotland – from the sky.

His bosses refused: they thought he was asking on a whim and suggested he take a taxi instead. But Crawford was stubborn. He took leave and paid for the aircraft himself. The trip above the Scottish lowlands cost him £27 – equivalent to several thousands pounds in today’s money.

‘The bony skeleton of an old horse’

What made the aerial perspective so revolutionary when it came to the study of the past? From the air, Crawford said, the tracery of the ancient world showed up like ‘the bony skeleton of an old horse’. The landscape emerged as a ‘document that has been written on and erased, over and over again’.

At the right time of day the landscape reveals secrets that are only visible from above – long shadows cast by ancient earthworks, lines in crops or soil left behind by structures built long ago

And, crucially, it was a document that no one had ever read before. When Crawford made his tour in the summer of 1939, the conditions could not have been better. ‘A long drought had burnt up the grass’ he reported. And as a result, the traces of the past were inscribed in the landscape of Scotland with startling vibrancy: ‘as if’ he wrote, ‘they had been painted in vivid green on a brown canvas’.

Yet these signs were merely fleeting. ‘We were fortunate in catching the last week of this drought’ Crawford said, ‘the weather broke on the day that we flew south’. The rains came, and washed the glimpses away.

For that one, blissful week, however it was thrilling stuff. It felt like the future to Crawford – technology revealing, with almost shocking suddenness, how the living share the land with the dead. How ghosts are, in a sense, all around us all the time.

‘The young archaeologist must learn to fly’

‘The moral is obvious’ he wrote. ‘The young archaeologist who wants to make discoveries must learn to fly. Not until then will the harvest be reaped’. Our past was still an ‘unexplored country’. Aerial photography, he pronounced, was to the archaeologist what the telescope was to the astronomer. Before it, they had been squinting into the dark. Now they could really see.

For Crawford, the new generation of archaeologists had to operate among the clouds. So much of the ancient world was just waiting to be uncovered. ‘The exploration of Scotland from the air has only just begun’ he wrote. ‘It is one of the most promising fields of research anywhere in the world’.

The search for the ‘lost world’ Crawford had discovered from the air would have to wait. Three months after his pioneering flight, Britain declared war on Germany.

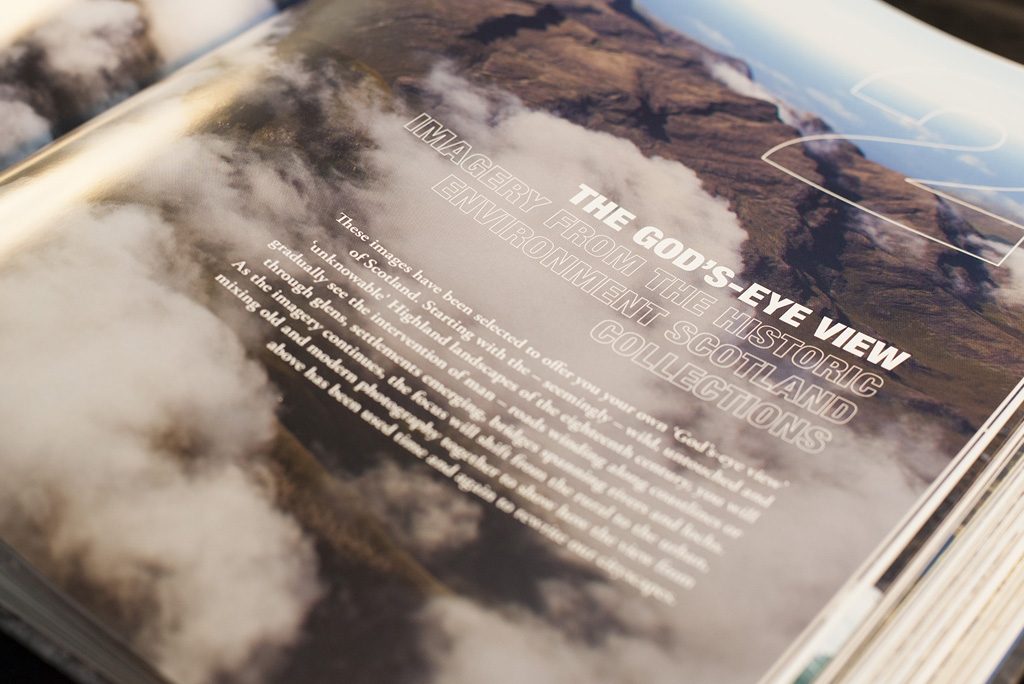

To find out more, read Scotland from the Sky, RRP £25, available from all good bookshops including the HES online shop!

You can also watch episodes on iPlayer now.