Every tree tells a story – about history, about people and about the environment. Despite spending my life working with buildings, recently I’ve become a massive tree fan. Because it’s National Tree Week I’m taking this opportunity to share some thoughts and stories about trees, timber and the historic environment.

Counting rings

Did you ever try to work out the age of a tree by counting its rings? Dendrochronology (dendro = tree; chronos = time) is a branch of archaeological science which focuses on tree-growth rings. It can be used to examine living trees as well as the wood inside historic buildings.

If you have the appropriate permissions for working on a historic site, a sample can taken by boring a small core (about the diameter of a drinking straw) or by photographing the end grain of a timber. Under a microscope, the tree “rings” look like a bar code. By fitting their pattern into other known examples, you can sometimes identify exactly when the tree was felled, and roughly where it grew. These results tell us about architecture and trade in the past.

A core sample of a roof beam at Newark Castle

Isn’t it good, Norwegian wood?

A few years ago, samples from the roof of the great hall at Edinburgh Castle were analysed. We now know that the oak trees which made these beams were felled in Norway between 1505 and 1509 and then shipped over to Scotland.

Down in London, the National Portrait Gallery used dendro analysis to verify a portrait of Mary Queen of Scots. It was thought to be an 18th century copy, but dendro proved the wooden board it was painted on dated from between 1560 and 1580, and so the portrait was probably painted during her lifetime.

A year in the life

As well as helping us understand buildings, dendro also helps us understand climate change. Each year of a tree’s life is recorded in the pattern of growth rings in its trunk: summer growing and winter “resting”. Good growing years leave wider rings than poor years; temperature and rainfall are the key factors.

This means that (with some whizzy statistical analysis) climatologists can turn tree rings into a fairly accurate picture of Scotland’s weather and climate going back 2000 years.

Woodland has always been an important resource from Neolithic times onwards. The size and quality of the trees available to our early ancestors is quite amazing: check out the Carpow Log Boat in Perth Museum.

The boat is 9m long and was carved from a single oak tree about 3000 years ago. It was found in the banks of the River Tay.

Even older than the logboat, but still going strong in a churchyard in Perthshire is the Fortingall Yew, probably the oldest living tree in Britain. And that brings me onto living trees…

Mighty oaks

Less than 5 % of Scotland’s land area now supports native woodland. This includes species such as oak, ash, birch, alder, hazel, hawthorn, holly, willow and Scots pine. Only about 1% of Scotland’s woods qualify as Ancient Woodland (woods in existence since at least 1750). They are a rare and vulnerable resource.

Within Chatelherault Country Park, near Hamilton are some of Scotland’s most important and beautiful trees. The oldest oak here started its life in about 1440. Many more date from the 1500s.

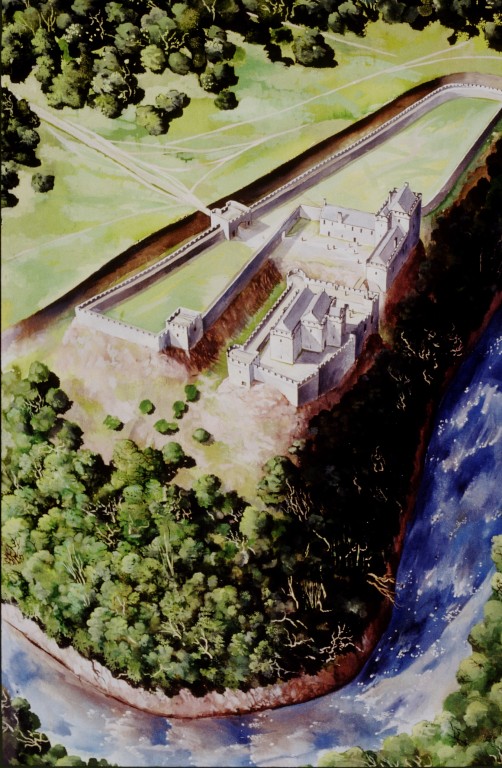

They grow on top of earlier “rig and furrow.” This probably means that the oaks were deliberately planted on cultivated land which was being given over to a hunting park. During the 1500s the Hamilton family began building nearby Cadzow Castle, which survives only as a ruin.

Artist’s bird’s-eye view of Cadzow Castle

Ageing gracefully

The great thing about these venerable trees is that as they decay so gracefully and so generously. They support whole ecosystems of insects, mosses, lichens and funghi – many more than they did as younger trees. In biodiversity terms they are at their peak of usefulness near the end of their lives! They are also incredibly beautiful to look at, draped in moss and festooned in ferns and full of the sound of birds.

Trees are genuinely amazing. They are a key part of the historic environment. They can tell us many stories of the past, but they’re also critical for our future.

There are a number of resources which will help you find out more about Scotland’s trees including Scottish Natural Heritage, the Woodland Trust, the Ancient Tree Forum and The Native Woodlands Discussion Group.