In a globally tumultuous time, it’s important to do a “healthcheck” on Scotland’s historic environment. Are we prepared for what lies ahead? What does our history and heritage mean for Scotland, both locally and further afield?

Every two years, we publish Scotland’s Historic Environment Audit (SHEA). SHEA, pulled together with the help of the whole heritage sector, gives a snapshot of the challenges, successes and trends over time that impact our historic environment.

Here are the top five themes we’re seeing in 2018.

Millennials and Generation Z are connecting with our historic environment. Green spaces like Holyrood Park are especially appealing to younger Scottish adults.

1. Generations X and Y are local history lovers

Historical places are being visited more and more. In 2017, 35% of Scottish adults visited a historical or archaeological place, an increase from 28% in 2012. But while we’re seeing an increase of interest in all age groups, the biggest increase of visitors are amongst younger people.

Millennials and Generation Z are leading the trend in Scotland by showing an interest in history and heritage. We’re now as likely to find a 21 year old exploring the nooks and crannies of a castle or enjoying a scone in the café as someone in their 60s.

The number of 16-24 and 25-34 years olds visiting historic places has increased by 10% and 11% respectively since 2012.

This is a trend that we’re likely to see continue as initiatives during the Year of Young People, such as £1 entry for Historic Scotland sites, are encouraging an influx of younger visitors.

Added to that, the influential power of Instagram on young visitors is impressive. Social media-savvy travellers, locals and tourists alike, are increasingly finding their destination inspiration through the fastest growing platform. VisitScotland, taking note of the latest tourism trends, opened the world’s first Instagram travel agency at the end of last year.

£41.5 million has been awarded to 63 separate Conservation Area Regeneration Scheme (CARS) since the scheme was introduced in 2007.

2. Investing in heritage = investing in Scotland

As a nation, we are putting more and more funding into looking after our historic environment – and we’re getting more and more back from it. In 2017, Scotland’s heritage contributed £4.2 billion to Scotland’s economy, up from £3.4 billion in 2014.

Recognising the cultural, economic and health and wellbeing benefits of heritage, an estimated £1.2 billion (including grants) was spent on Scotland’s heritage in 2017. Over the past 3 years alone, this has increased by £200 million. Between 2014-18, the biggest investments from the public and voluntary sector has been from:

- Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF)

- Historic Environment Scotland (HES)

- National Trust for Scotland (NTS)

- Local Authorities

But it’s not all from the public sector. Private investment accounts for three quarters of all the finding for the historic environment. This is because most heritage assets like listed buildings are privately owned and historic places feature prominently in Scottish life.

Which brings us onto…

It’s not only Scotland’s people that need extra care as they grow older.

3. One in five of us live in a historic home

It’s well known that Scotland has an aging population. But it’s not only Scotland’s people that need extra care as they grow older.

The latest Scottish House Condition Survey (SHCS), the largest single housing research project in Scotland, shows that almost half a million dwellings in Scotland now date back to the end of the First World War or earlier – meaning almost a fifth of Scottish households live in a historic home.

Poorly working cast iron rain goods are often directly responsible for damp walls. Leaking gutters and overflowing downpipes are common problems in traditional homes.

4. Common problems are increasing – but buildings in need are getting support

As our buildings age, and in the face of continuous risks from climate change, the challenge of maintaining traditional properties is increasing.

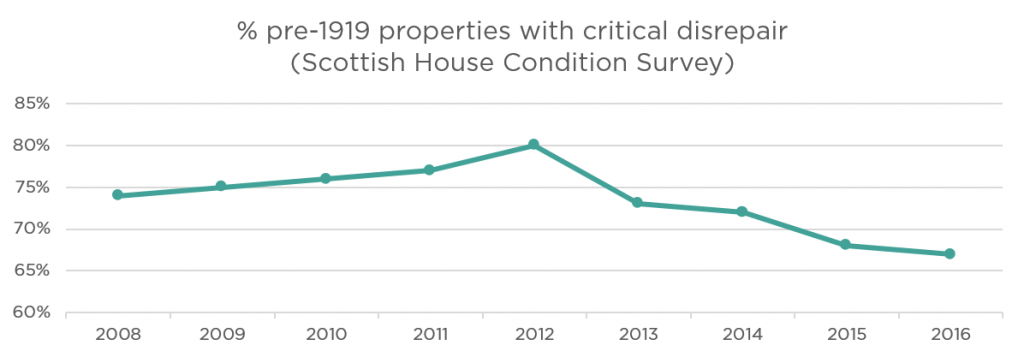

Common problems, often caused by more rain, such as damp walls and decaying timber windows, will be familiar concerns to people living in a historic home. The most recent data from SHCS shows that 67% of pre-1919 dwellings in Scotland are in need of critical repairs, such as structural stability and weather tightness.

But the latest SHEA report shows that Scotland is stepping up to the task of caring for its aging buildings.

Data source: Scottish House Condition Survey (SHCS)

The number of historic buildings in need of critical repair is now on a downward trend from a peak of 80% in 2012. SHEA also highlights that 83% of scheduled monuments are recorded as being in an optimal or generally satisfactory condition.

Buildings can often be rescued and restored, but these aging figures that populate our towns, cities and countryside need care and attention before they’re beyond help. To support private owners to continue caring for their historic buildings and places, and ensure the long-term survival of the historic environment, organisations like ours share expert advice with building owners and professionals to ensure best practice in maintenance and repair.

The Engine Shed is our conservation centre, providing access to expert advice on caring for traditional properties.

The Engine Shed, which we opened to the public last year, is a conservation hub dedicated to providing even more support and guidance on maintaining traditional buildings.

Since 1974, New Lanark Trust has transformed a derelict site into one of World Heritage status. In 2017, the last block of former millworkers’ housing was restored from a vacant and dilapidated terrace on the Buildings At Risk Register to residential housing.

5. Scotland is on a mission to rescue and restore

Another good news trend from the SHEA report is the success story of the Buildings at Risk Register. This platform was established in 1990 to raise awareness of buildings that are listed or in Conservation Areas but vacant or in disrepair.

Since SHEA began recording data on Scotland’s historic environment in 2008, we’ve seen over 750 historic buildings on the Register saved. In total, the scheme has helped save almost 2,000 buildings and more than 200 others are currently in the process of being restored.

We work with developers and individuals to bring buildings back into use, but with the introduction of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015, giving community bodies in Scotland the right to buy, we hope even more buildings at risk will be given a new lease of life through communities. With the right care, they will last the next 100 years and more in new roles benefiting local communities.

Looking ahead

It’s great to see that the sector is in a strong position to face the challenges ahead. There is still much work to be done to understand the current and changing condition of the historic environment. But SHEA paints an encouraging picture for our historic environment and how we’re working together to look after it.

Find out more about SHEA and the data that reveals these trends:

- SHEA Reports and Data

We’ve published the SHEA data for anyone to undertake their own analysis and interpretation of the state of the sector. - SHEA case studies available from the Built Environment Forum Scotland (BEFS)