As Victorian love affairs go, it wouldn’t be out of place in an epic period drama.

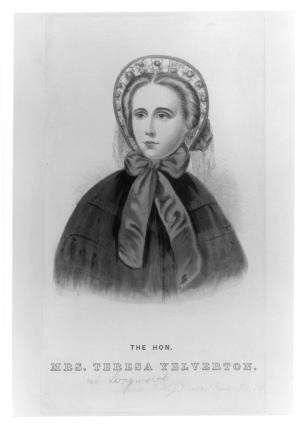

Maria Theresa Longworth was the 22-year-old daughter of a successful English merchant. William Charles Yelverton was the son of a Viscount and a major in the Royal Artillery.

Their romance began by chance in the summer of 1852 on a cross-channel ferry from Boulogne to London.

An international romance

Correspondence followed, before a second meeting took place in the autumn of 1855 in the Crimea, where Longworth was serving as a nurse and Yelverton was on military duty.

The pair were reunited in Edinburgh in 1857. Yelverton, stationed at Leith Fort, frequently visited Longworth at her New Town lodgings at 1 St Vincent Street.

By April 1857 they “had acknowledged and declared each other to be husband and wife.”

A view of St Vincent’s Street . Number 1 is located opposite the parked cars, just below the gardens.

The declaration was followed by two marriage services. A Church of England ceremony was held, whilst in August 1857 a Roman Catholic service took place in Ireland in accordance with Longworth’s religion.

Between August 1857 and April 1858 Longworth and Yelverton cohabited and lived as husband and wife in Ireland, Scotland, England, and France.

Scotland on horseback

The Scottish part of their cohabitation included a horseback tour in the autumn of 1857. They visited such places as Linlithgow, Falkirk, Stirling, Callander, Dunblane, and Dunfermline. During this time the couple were received as husband and wife.

Yelverton later stated that during the trip he and Longworth had sexual intercourse on numerous occasions, explaining that:

The excursion was undertaken chiefly for the purpose of obtaining more convenient opportunity for this indulgence.”

On 6 November 1857 the pair visited Doune Castle, appearing in the visitors’ book as ‘Mr & Mrs Yelverton’.

Doune Castle.

Where did it all go wrong?

In 1858, the seemingly-passionate relationship began to turn sour. In France, Longworth suffered ill-health and a miscarriage. Yelverton, meanwhile, had abruptly left for military duty and was in financial difficulty.

In June, Yelverton married a Mrs Emily Forbes, widow of Professor Edward Forbes of the University of Edinburgh. Forbes had reportedly inherited some £50,000 from her former husband.

It seems that Yelverton had completely dismissed his declaration made in Edinburgh, along with the two marriage ceremonies. Longworth received a letter stating:

All connection between Major Yelverton and Miss L. should now cease’.”

Yelverton even offered to pay for her to emigrate to New Zealand!

Fighting back

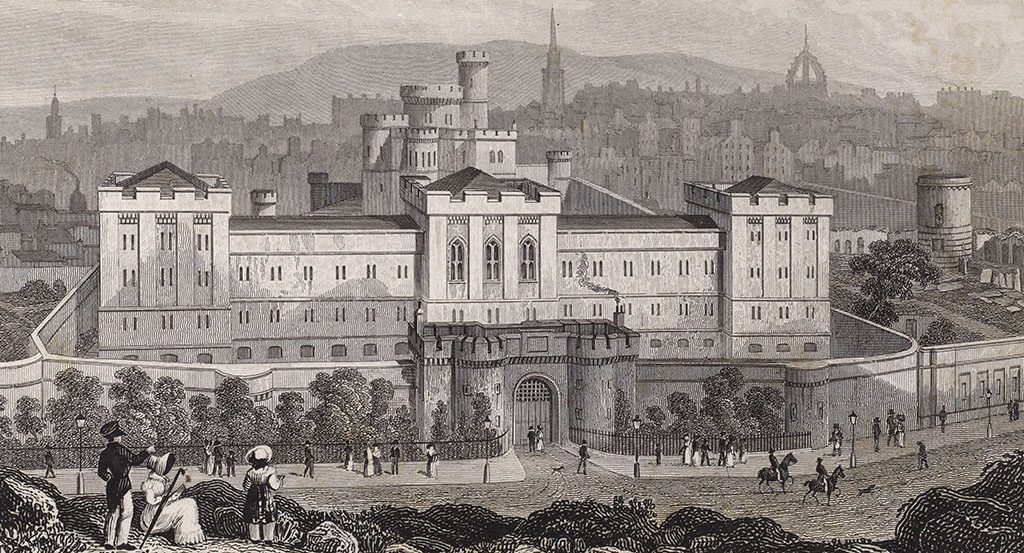

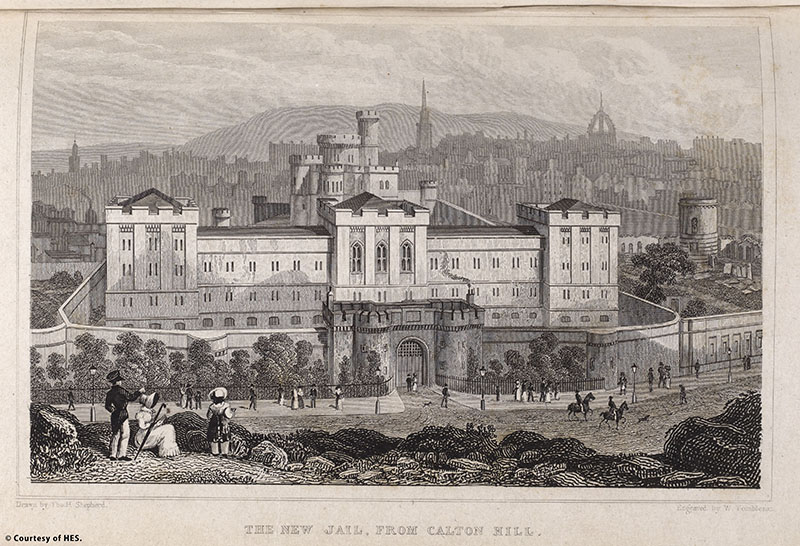

An outraged Longworth refused to accept what had happened. She accused Yelverton of the crime of bigamy in October 1859. Yelverton spent some time in Edinburgh’s Calton Jail but was released due to a lack of evidence.

An engraving of Calton Jail, c. 1830.

In January 1860, determined to protect her status and reputation, Longworth brought a case of declarator of marriage against Yelverton. In short, she wanted to prove once and for all that the pair were legally married.

Yelverton found himself embroiled in a scandal. He was suspended from all military duties and forced to live on half pay. He denied bigamy. He argued that Longworth had pursued him relentlessly but their relationship – including that red-blooded horseback tour – had always been illicit.

In 1861, a Dublin court took less than an hour to accept the validity of Longworth’s marriage to Yelverton. But the case still needed to go through a Scottish court.

Doune to the rescue

Remember how the couple had signed the visitor book at Doune Castle in November 1857? It was to be a turning point during the hearing in Edinburgh.

Court records report how “Donald McDonald, keeper of Doune Castle, residing at Castle Cottage, Doune” testified:

I am about fifty years of age… and desired to produce the visitors’ book kept at Doune Castle, more especially with reference to the year 1857.”

The signed visitor book had been produced as evidence in the case. Examined as a witness, Mr McDonald recalled:

I perfectly remember a lady and gentleman coming on horseback in November of 1857…I thought they were man and wife. She was a person of ladylike appearance. She did not strike me as a flighty, light person.

I showed them through the castle. I saw the gentleman enter their names as Mr and Mrs Yelverton.”

The court ruled in favour of Longworth. Her marriage to Yelverton was confirmed.

Victory?

Longworth’s victory was not to last. Yelverton successfully took an appeal to the House of Lords. His first marriage was declared invalid and Emily Forbes was recognised as his lawful wife.

Theresa Longworth was ordered to pay him £50 in damages.

Legacy

The Longworth-Yelverton affair left a lasting legacy. It inspired J. R. O’Flanagan’s novel Gentle Blood (1861) and Cyrus Redding’s A Wife and not a Wife (1867). The case also set a legal precedent which led to the Marriage Causes and Marriage Law Amendment Act of 1870.

Longworth supported herself by writing. Her works include Martyrs to Circumstance (1861), The Yelverton Correspondence, with Introduction and Connecting Narrative (1863), Zanita: A Tale of the Yo-Semite (1872), and two travel books.

Theresa (pictured above in later life) died in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, in 1881.

She never gave up her argument. At the time of her death she was referring to herself as Viscountess Avonmore: a title exclusively reserved for the wife of none other than The Honourable William Charles Yelverton.