Designed by an Irishman and built by a labour force that included African American slaves and European immigrants, the White House represents the history of a new country built by men and women from all over the globe.

From overseeing the quarrying of stone to lending specialist skills to intricate masonry, workers from Scotland made a fascinating contribution to the vast and historic construction of the American presidential residence.

This is the story of the Scots Who Built the White House.

Planning the White House

The White House was conceived as a statement of independence and power. It was to be located in Washington, a new U.S. Capital founded beside the Potomac River in 1790.

After an initial design proved too costly, in March 1792 Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson announced a competition for architects to submit plans. The winner would receive a cash prize and a medal.

Leinster House, Dublin – inspiration for the White House

The commission was won by a young Irishman named James Hoban. His design was modelled on Leinster House in Dublin

To reflect the majesty of the presidency, George Washington had insisted that the White House be built of stone and be decorated with ornate carvings.

The work would require at least 30 skilled stonemasons – and the city commissioners knew just where to find them…

The Athens of the North

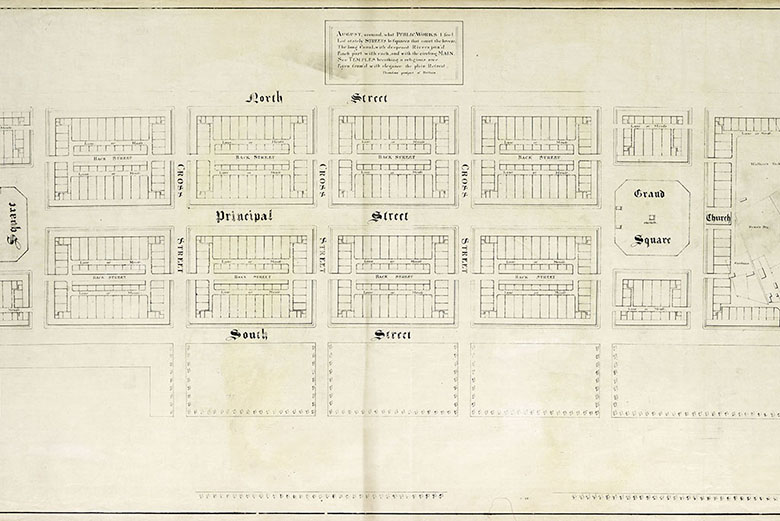

Plans for Edinburgh’s New Town, begun by architect James Craig in the 1760s. The arrival of the New Town transformed Edinburgh from ‘Auld Reekie’ to the ‘Athens of the North’ and helped Scots masons hone their skills.

Edinburgh in the 18th century was a rapidly expanding city. “The Athens of the North” was home to many of the greatest minds of the era such as Adam Smith and David Hume, influential friends to American Founding Father Benjamin Franklin.

The neo-classical squares, crescents and gardens of Edinburgh’s New Town reflected Enlightenment ideals of reason, liberty and progress.

The architecture involved provided perfect training for local stonemasons, who worked with many different types of materials from ornate Devon stone to volcanic rock.

Arthur’s Seat, a dormant volcano in the heart of Edinburgh. Local stonemasons were used to working with volcanic rock.

From war to Washington DC

In 1792, Britain was at war with France. The government banned skilled labourers from emigrating during the conflict. Many skilled craftsmen were left with no work to do.

Enterprising commissioners in the States seized their opportunity. They turned to Scotland to find the skilled workers required for the White House project. Offering generous wages and covering travel costs, they persuaded some 12 unemployed stonemasons to defy the government’s ban and travel to America.

A good place to source skilled workers was the Freemasons. These “brotherhoods” of tradesmen protected and promoted their craft within small, select groups called Lodges.

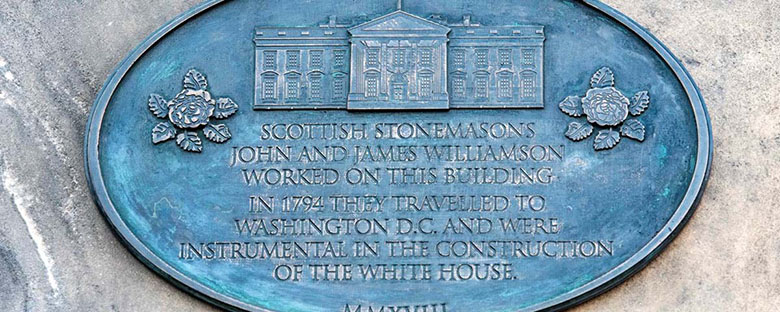

Around six members of Edinburgh Lodge No. 8 including brothers John and James Williamson decided to make the long journey to Washington DC. Did they know as they crossed the Atlantic that their stone-masonry skills would soon make history?

A commemorative plaque to John and James Williamson at 66 Queen Street in Edinburgh. They worked on the building before they travelled to Washington D.C.

Building the White House

Another Scot – and another Williamson – was employed to oversee the work of the stone-cutters. This diverse community was responsible for quarrying the material for the White House. It was transported to the building site by ship from Aquia Creek in Virginia.

Collen Williamson was an elderly master mason from Moray, Scotland. He was a capable leader and succeeded in the tremendous task of cutting and transporting a staggering 99,000 cubic feet of stone.

But Collen had a fiery temper. He wasn’t afraid to argue about his workers or complain to the commissioners. He frequently clashed with James Hoban and by the end of 1795 his contract had been terminated.

Despite his vital role in sourcing the raw material needed to build the White House, very few were sorry to see him go.

Specialist Scottish Skills

Intricate stone carvings around the North Door of the White House. This image and cover image © The White House Historical Association

Thanks to their experience back in Edinburgh, the Scots stonemasons had exceptional, adaptable skills.

Even though Aquia Creek sandstone was different from material they had worked with at home, they were still able to carve hundreds of individual works of art onto the White House.

One of the most beautiful and characteristically Scottish of the White House carvings is the ‘Double Rose’. It can be seen in numerous places on the building.

The carvings were based on the Scottish Double Rose, cultivated by the Royal Botanical Gardens in Edinburgh in 1780. The rose was associated with migration and homecoming. It was particularly fitting that it inspired the Scots stonemasons working in America.

A timeless craft

Today, the White House is recognised worldwide for its striking appearance, and the legacy of the Scots stonemasons lives on.

During a major restoration in the 1980s and 1990s, over 40 individual mason’s marks were discovered on stone carvings. Many were the distinctive mark of Scots workers.

In 2018, a Historic Environment Scotland stonemason from Carnoustie in Angus, Charles Jones, travelled to Washington to replicate a Scottish Double Rose originally carved over 200 years ago.

Using traditional tools, he worked in the gardens of the White House just as his predecessors had done.

You can delve even deeper into the intriguing transatlantic story by exploring a new exhibition at the Engine Shed, our conservation centre in Stirling. For more history of the White House visit the White House Historical Association.