While the emphasis of climate change tends to be geared towards its effects on the future, the focus rarely tends to look to the effects that it’s having on our past.

We’re seeing more heavy rainfall, rising temperatures and rising sea levels in Scotland. For some sites and monuments, the effects of this could be devastating.

As part of the Adapt Northern Heritage project, collaborating with project and associated partners, we’re looking at how we can support communities and local authorities adapt to these impacts through community engagement and conservation planning.

We take a look at what’s been discovered by the project’s Scottish case studies so far.

Flooding at Threave Castle

What’s wrong with this picture?

While it may look like the stronghold of the Douglas family has taken protective moats to a whole new level, the level of surrounding water is actually believed to be caused by climate change!

The historic Threave Castle was built by Archibald the Grim in 1369. It’s had many dramatic moments in it’s history, including a two month siege involving James II.

The surrounding River Dee means visitors can enjoy a lovely sail over to the castle by boat. However, increasing rainfall caused by climate change can also cause the river to flood. The river itself makes up 90% of the flood risk to the castle.

At worst, and without taking measures to protect the castle, increasing rainfall in this area could cause wash-out of the castle’s mortar, deterioration/loss of archaeology in the surrounding grounds and restricted access to the site.

That’s why, as part of the workshop, we’ve explored options such as a conservation technique called soft capping – so visitors can continue to enjoy a trip to this forbidding island fortress and we can extend the castle’s life!

Falling trees at Threave Estate and Gardens

Just a stone’s throw away from Threave Castle is the picturesque Threave Garden and Estate. Unlike our other Scottish case studies, a major focal point at Threave Estate is the garden with its diverse flora. A combination of increased CO2, increased precipitation and warmer temperatures has led to an increase in growing season by around 25 days since 1961.

Stronger winds in the summer are thought to contribute to a rise in falling trees. Some of the older trees in the gardens are hundreds of years old. They’re an equally important part of the estate’s heritage.

It seems biological heritage can be more adaptable than buildings, because plants can be re-located or the type of plants grown can be changed. On the other hand, it’s a lot less predictable.

This means that the best starting point for the garden is ongoing survey work and investigation. This will help us pool knowledge for the prediction of future risks.

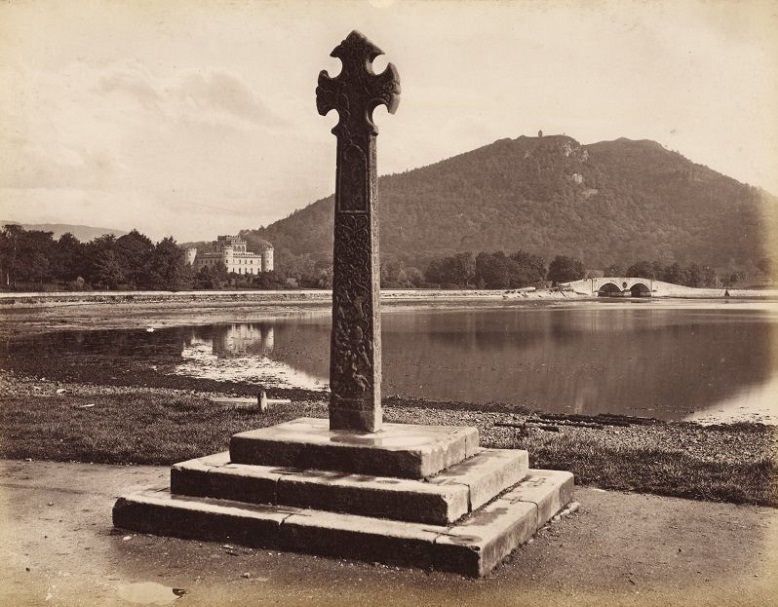

Storms and rainfall at Mercat Cross, Inveraray

Mercat (Market) Crosses like this were frequently found in Scottish cities, towns and villages. Historically, they were symbols of a burgh’s right to trade. Townsfolk would gather around them to listen to public announcements. But earlier examples had a much darker purpose…with criminals tied to the cross as punishment and worse!

This 15th century Mercat Cross lies in the historic town of Inverary in Argyll and Bute. It’s a picturesque place on the western shore of Loch Fyne.

It’s thought this cross once stood in a medieval burial ground, and it certainly has stood the test of time! Now, it in its open position over-looking the town’s harbour, it’s in danger of being weathered with increased storms and rainfall in the west.

While protect structure could be protected, for example by building a glass case around it like Sueno’s Stone or moving it to Inverary Castle, an alternative approach could be to monitor deterioration of the material over a set period of time and schedule repairs accordingly.

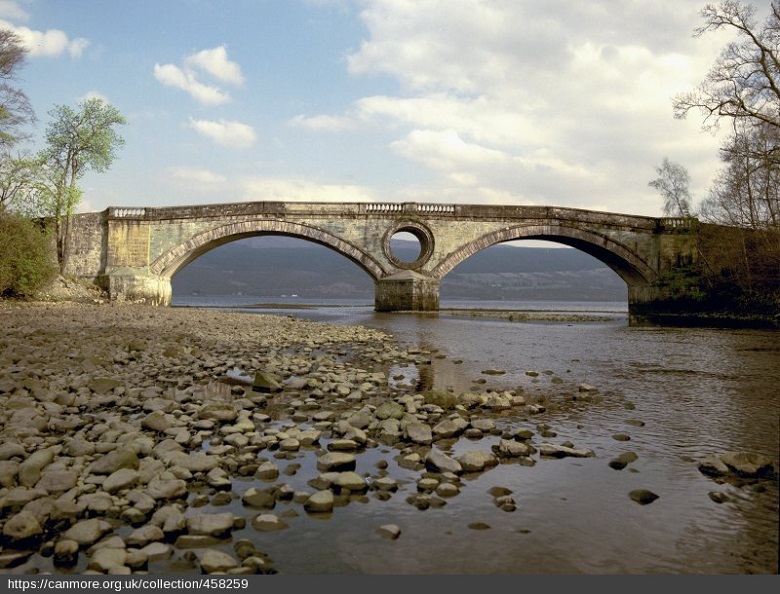

Heavy river flow at The Aray Bridge

The 18th century Aray bridge is a vital part of Inveraray. As well as being an A-listed heritage site, it’s also the main route through Argyll and Bute.

The original bridge was designed in 1758 by John Adam, who designed Dumfries House with his prolific architect brother, Robert Adam. This military bridge was destroyed by flooding in 1772.

When the new bridge was built, changes were made. However, climate change means more adaptation measures will have to be put in place to protect this bridge so communities can continue to use it well into the future.

© Courtesy of HES (A Brown & Co Collection)

Projections suggest that coastal flooding and heavier rainfall are likely to increase over coming decades. This leaves bridges like this more at risk.

So how can the Aray Bridge be protected? More recording and investigation is needed to understand the effects of the river flow here. Dredging could be one temporary solution. It is, however, hotly debated as to whether dredging actually eases the effects of climate change.

Next steps for our climate heritage project

In addition to our two Scottish sites, the Adapt Northern Heritage project has been looking at the effects of climate change on heritage in Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Russia and Ireland since 2017.

Ballinskelligs in Ireland

Together, we’ll develop a risk and vulnerability assessment method for historic places and associated guidance for their adaptation. By working with local experts and engaged communities, we can hopefully safeguard these heritage sites against the detrimental effects of climate change.

Keep up to date with the Adapt Northern Heritage project by following us on Twitter and Facebook or sign-up to our newsletter.

As the project draws to a close in May 2020, we’ll be hosting a concluding international conference from Tuesday 5 to Friday 7 May 2020 in Edinburgh. Find out more about the conference and buy a ticket now.