Whether you are a seasoned archaeologist, or a history lover interested in the latest archaeological developments, you will likely appreciate the importance of data (especially, spatial data) to our understanding and interpretation of the past.

Archaeology is a location-focussed discipline. The study of past human activity creates a wealth of information through fieldwork or scientific enquiry, all of which has a geographic component or can be linked to a specified place.

Archaeologists build up an understanding of the past over time through a series of observations from desk-based assessments and separate fieldwork activities. Each geophysical survey or excavation we complete adds another piece to the jigsaw to improve our understanding of the past.

3D laser scanning is one example of fieldwork and surveying. The data from this scan at Rough Castle Fort has improved archaeologists’ understanding of the Antonine Wall.

As a sector, we are very good at publishing the locations of these fieldwork activities… but less so in systematically recording and reporting on the activities themselves.

The challenge of data-driven decisions

Data we collate from fieldwork and related research provides us with crucial evidence that can inform the way we look after the historic environment. For example, we use data as a benchmark from which we can monitor and measure the impact of climate change and coastal erosion over time.

Data is an essential tool to help us track the impact of climate change and make informed decisions on caring for the historic environment, like at Threave Castle.

But, despite the enormous potential and benefit of data-driven decisions, the established working practices for the use and reuse of spatial data in Scotland are inefficient, leading to information loss and duplication of effort. As I type, there is no coordination in collating and publishing the primary evidence from fieldwork undertaken by archaeologists across Scotland on which we all base our decisions on.

Although location plans are often created digitally during fieldwork or in writing up, they are typically only accessible as an illustration in the project report which limits the opportunity for reuse. When needed, the footprints of archaeological investigations are re-digitised from plans – an inefficient process that introduces errors, potentially at the expense of both our time and money.

With modern day archaeology becoming increasingly digital, there is an opportunity for the sector to combine our place-based data and reduce errors or duplication of work.

With the digital technologies available today, there is a real need for a new approach to maximise the value of expensively gathered geospatial data. We believe that the problem can be addressed through a Spatial Data Infrastructure (SDI). This would provide the framework, guidance and rules to organise, standardise and share archaeological data.

The challenge is to combine spatial data from everyone undertaking archaeological fieldwork into a series of thematic map layers in the same formats. This will allow evidence from airborne mapping to be viewed alongside data from remote sensing surveys or where excavations have taken place.

A Spatial Data Infrastructure would allow data from excavations like this one at Dunstaffnage Castle to be easily shared across the sector and compared with other research.

Spatial data: the story so far

Historic Environment Scotland (HES) publishes Protected Sites Data on our Heritage Portal. This is information about Scheduled Monuments, Listed Buildings and other designation datasets. We’re directly responsible for creating and maintaining this data and display it on PastMap, free for the public.

PastMap shows you information about historic sites and landscapes all over Scotland, brought together on maps spanning from 1843 to the modern day.

Further afield, through the Infrastructure for Spatial Information in Europe (INSPIRE) Directive in 2007, public organisations across Europe are required to share environmentally related spatial datasets to support decision making and management of the environment. We share our data through Scottish Government’s Scottish Spatial Data Infrastructure portal, which is then used by the INSPIRE Geoportal.

While INSPIRE has an environmental focus, there is limited guidance for archaeological datasets. Much of the data in INSPIRE is created outside, but ultimately curated by, the public sector. Reflecting our own data challenge in Scotland, despite the richness of data in INSPIRE:

- the lack of consistent and appropriate data standards places a barrier for interoperability

- too often datasets created digitally are reduced to illustrations in a report, limiting reuse in a digital environment

- where preserved, the data is not easily discoverable

- many organisations create data but there’s no mechanism or requirement to collate it into accessible services

While a step in the right direction, the potential for spatial data created through archaeological fieldwork and research is not being realised.

Missed opportunities

To demonstrate the benefits of new approach and vision, we’ve looked at the excavations at Lockerbie Academy as a case study.

In 2006, excavations by CFA Archaeology Ltd revealed traces of an Early Medieval timber hall at Lockerbie Academy.

Evidence for Neolithic and Early Medieval timber halls were revealed in excavations by CFA Archaeology Ltd in 2006. The archaeological work was commissioned in advance of a development at Lockerbie Academy in 2006 and the findings were published as a PDF in an online open access journal, Scottish Archaeological Internet Report, in 2011.

By digitising the trench locations or using a digital copy of the data from the site plan, the data could have been accessible through a Geographic Information System (GIS) platform and used alongside other geographic datasets.

Mapping the extents of fieldwork is just the beginning. What we’d like to see as the result of a Spatial Data Infrastructure is a fully digital archaeological record, allowing detailed mapping and analysis of the features revealed during fieldwork.

Transforming spatial data

Another example of how spatial data might benefit the archaeological record and future research can be found at Inveresk Roman Fort in Musselburgh, East Lothian.

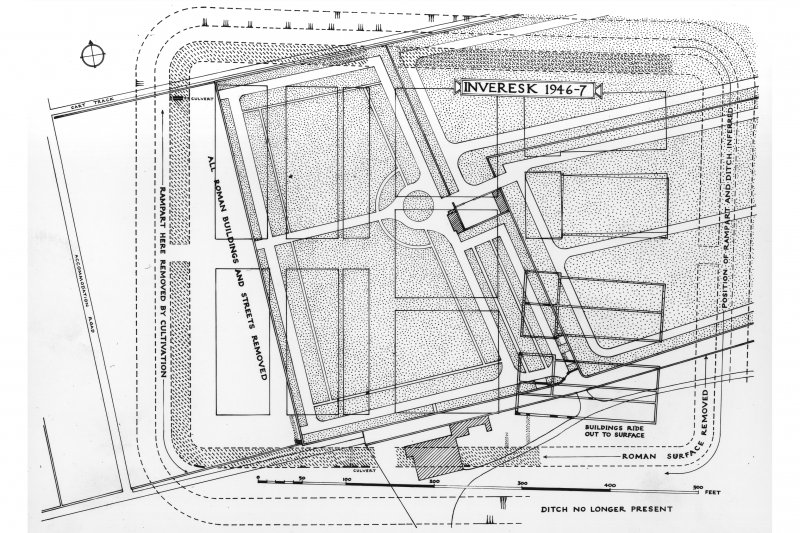

At HES, we hold detailed descriptive accounts of the Roman and other archaeological sites at Inveresk. For example, the Canmore record for Inveresk Roman Fort provides a lengthy commentary on the sequence of excavations at the site from the 1940s until the present day.

It also lists associated material from the HES Archives, including information and documents on one of the first excavations in the 1940s by Sir Ian Richmond’s excavations.

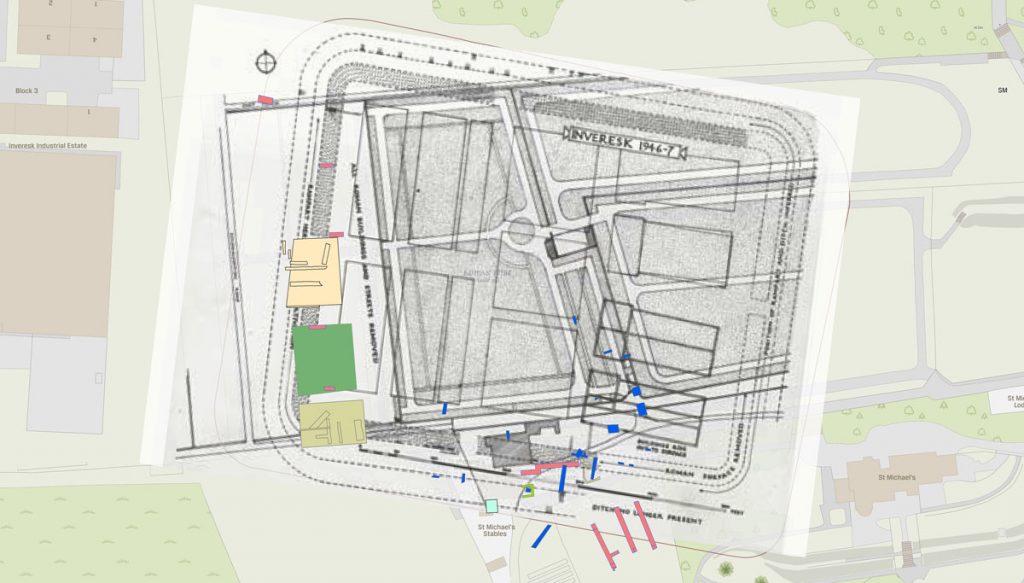

Inveresk is the most extensive and best preserved Roman settlement in Scotland. The site was first excavated in the 1940s (when these site plans were first drawn up), then 1970s and more recently in the 1990s.

Since Richmond first excavated the site, there have been many more archaeological investigations into Inveresk Roman Fort. Each produced a project report with the trench locations locked into the overall site plan. Each report may be consulted individually and offers great information, but the cumulative value of being able to build up a map of all the excavations that have taken place at the Roman Fort is worth significantly more.

Georeferencing the 1940s plan of the fort alongside more recent excavations and modern Ordnance Survey maps provides us with more context in understanding the site and making decisions on future research. (Background map © 2019 Ordnance Survey)

Going forward: our archaeological future

Recognising the many benefits of a Spatial Data Infrastructure, we have begun a project to challenge established practices of fossilising spatial data within project reports and as items of archive.

‘Towards a Spatial Data Infrastructure for Archaeology’, led by us at HES and funded through the Royal Society of Edinburgh, will show the need for managing and sharing data more effectively for the benefit of archaeologists, land managers, planners and the wider public.

We believe there’s a need for a consistent approach to spatial data from creation to curation and reuse – across both the private and public sector

As part of our project, we’ll be delivering a manifesto challenging archaeologists to make more of the data they create for the benefit of the profession and help improve our appreciation of the heritage around us.

Get involved

We will be holding a workshop for archaeologists in Stirling on Thursday 12 December. Anyone interested in making the most of our spatial data is welcome to attend.

Find out more and register for a place before Monday 2 December 2019.