How do you monitor an Iron Age monument located on a remote, deserted Shetland island? How can you tell when it was last conserved or trace historic works on it? Using digital documentation and by delving into archives, Li Sou is building the biographies of three fascinating Shetland brochs as part of her PhD project with Historic Environment Scotland and the University of Bradford: Mousa Broch, Old Scatness and the broch at Jarlshof.

Why brochs?

Brochs are very well known across Scotland for their striking, dominating architecture. They’re some of the tallest prehistoric buildings in Britain, and how they were made is still a hot topic among architects, engineers and archaeologists.

The three Shetland broch settlements I’m researching are some of the finest examples of Iron Age architecture in the world. So much so that they are on UNESCO’s tentative list for World Heritage status.

At a towering 13 metres high, Mousa Broch is the tallest surviving broch. Old Scatness had a vast Iron Age settlement surrounding the broch, with many large roundhouses. And the archaeology of Jarlshof spans across many different periods. The late Iron Age wheelhouses there are exceptional!

Capturing brochs in 3D

In my research as part of a PhD funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Collaborative Doctoral Partnership programme, I’m using the latest digital documentation methods to look at brochs.

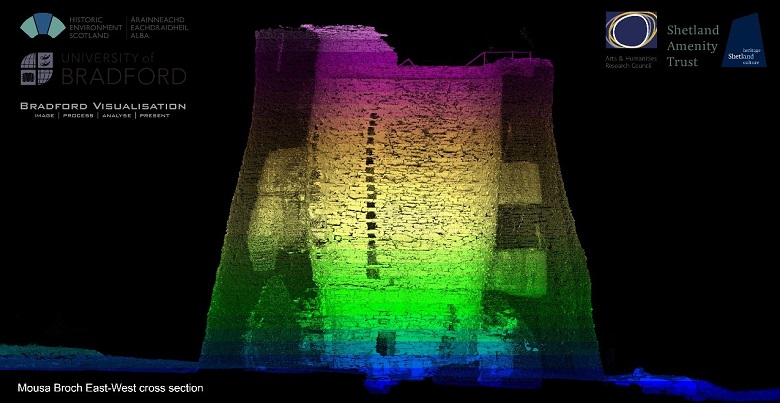

Using techniques like laser scanning, we have recorded these fascinating monuments in extremely high levels of detail. This means we can see the brochs accurately and in ways never seen before!

First, we surveyed Mousa broch using laser scanners. We captured 3D data of all areas of the broch, including the upper galleries that are not accessible to the public. And now you can experience it in 3D!

This 3D model created by Al Rawlinson, Historic Environment Scotland’s Head of Digital Innovation and Learning, is an invaluable source of information on the broch. You can really appreciate the thickness of the walls and see how carefully arranged the upper galleries are, with their ceilings and floors only a single flagstone thick.

Changes over time

Together with this new 3D data, I’m looking at existing records of the sites including reports, survey drawings, photographs and even some early laser scans. I’m comparing these with the new data to find new ways of monitoring sites for conservation.

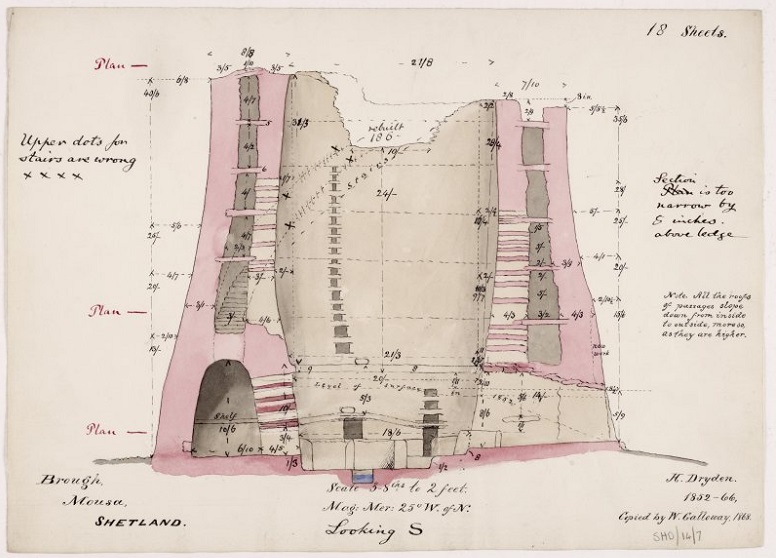

One of Dryden’s drawings of Mousa Broch from 1852-66, copied by W Galloway

At Mousa Broch, some very detailed survey drawings were made far back in the 1850s by Sir Henry Dryden, an enthusiastic archaeologist and antiquary. Dryden is remembered particularly for creating thousands of architectural and archaeological drawings of historic sites and monuments throughout Britain and Europe.

It has been very interesting comparing the records he made of Mousa Broch before it was a Scheduled Monument. He’d have most likely made his records only with the aid of tape measures and a theodolite (a surveying instrument with a rotating telescope).

Side by side, Dryden’s section drawings represent the walls in a much straighter and less curved profile than the 3D model. However, the external wall to the north matches the laser scan quite closely.

We must take the accuracy of his drawings with a pinch of salt as they are over 160 years old! In saying that, this does show how impressive it was for such a detailed record to be made so many years ago. At this time, the site would have been full of rubble and the inner cells were pitch black with no means to light them very well. You can appreciate the challenges he must have had to access all the different parts of the monument.

Next steps for the project

My research looking at differences between historic recordings and modern surveys is ongoing for my PhD. I’m really looking forward to working closely with the Historic Environment Scotland Digital Documentation and Innovation teams and Technical Education and Outreach teams at The Engine Shed to develop ways of sharing my findings over the next few months.

Keep an eye out on social media by following #RaeProject to see how the Rae Project progresses, and follow our digital documentation team Al Rawlinson, Lyn Wilson, and James Hepher.

About the author: Li Sou is a PhD researcher in Archaeology, working on her Collaborative Doctoral Project between the University of Bradford and Historic Environment Scotland. She loves exploring the past through all things visual.