Are you ready to come on a journey and encounter 3D impressions from a lost age of archaeology (aka ‘Squeezes’)? Archives Conservation Trainee, Ruby Smith tells us how she and our Archive Conservation team adjusted their usual archive practice to squeeze in some tricky material.

What on Earth…

We all know the moment: “How on Earth am I going to tackle this?” That seemingly impenetrable puzzle that at once perplexes and excites even the professional.

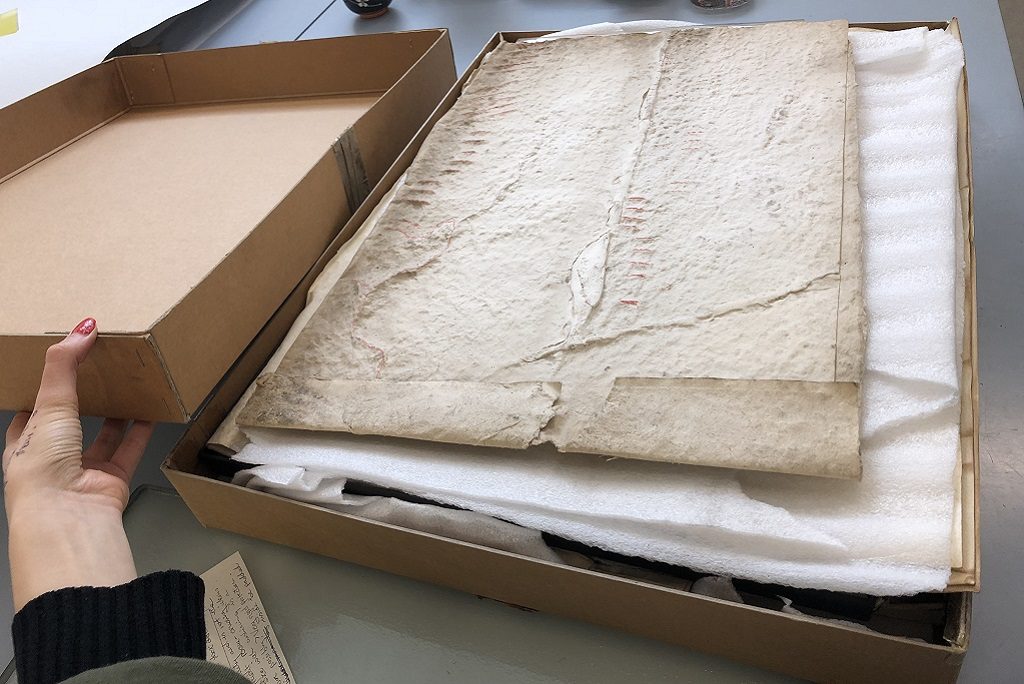

The Archive Conservation team and I were faced with such a moment when presented with some ragged cardboard boxes. They were filled to the brim with sporadic piles of papier mache, chalky plaster, and parcel tape. It was clearly historic, but what was it?

How were we to professionally conserve and store such knobbly, oddly-shaped material?

And here, we come to our starting point: what on Earth is a ‘Squeeze’?

The Lost Age of Squeezes

Our research began! Thankfully John Sinclair House is a building full of experts so we asked around. The archivists and historians told us that the Squeezes were essentially moulds and impressions, taken by archaeologists of the early to mid 20th century. Pictish engravings, fossilised shapes in stone, and rock formations were all recorded using the technique. The Squeezes within our collection ranged from fossilised footprints, to monument engravings.

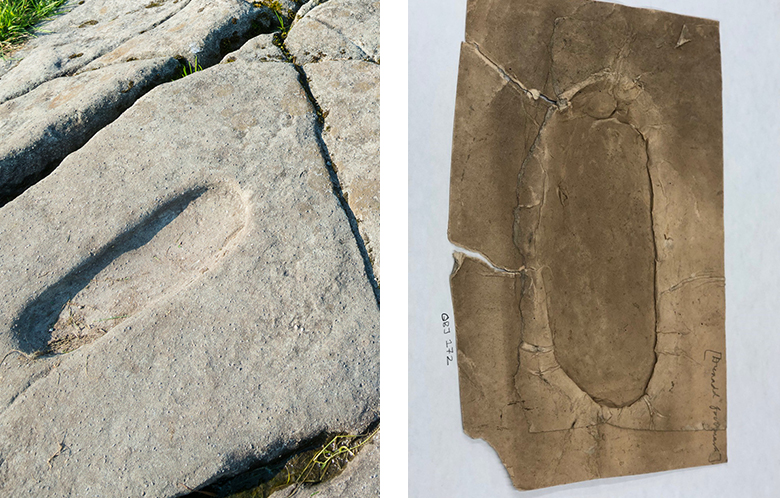

At some point, squeezes were used to record the unique carvings at Dunadd Fort. This rocky outcrop was home to a fort 2,000 years ago, and a royal power centre of Gaelic kings in the 500s to 800s AD. The carvings include a Pictish boar and pair of footprints. The stone footprints may have been used during inauguration ceremonies for new kings, symbolising the new ruler’s dominion over the land.

On the left, is the the most prominent of the carved footprints at Dunadd Fort. On the right is the impression taken from it, which is hosted in the HES archives.

Tantalisingly, we think the handwriting on the footprint squeezes matches that of James Hewat Craw, who excavated the site in 1929. However, we have no other evidence that they belong to his dig. If you have any information on this, please get in touch.

On the left, James Hewat Craw. On the right, a photo from the 1929 dig that Craw led at Dunadd Fort.

The process included moistening the squeeze paper, pressing it into the indentations of the site’s form, allowing it to dry, then proceeding to lift the now rigid impression.

These were then used for further study of the subject: whether that be ancient art methods, or geological processes. It meant that archaeologists could take the likeness of their findings to their offices, classrooms, conferences, etc.

We were fascinated, and were keen to know more. Did the media of Squeezes change over time? What do modern archaeologists use as a substitute?

A blast from the past?

Today at Historic Environment Scotland, new technology allows our archaeologists to make scans of sites and all of their dimensions, which can then be viewed digitally. Therefore the modern need for Squeezes has diminished largely in areas where there is a larger budget.

But modern technology doesn’t mean Squeezes aren’t important. They are exact moulds of many engravings in historical monuments and forms of ancient sites. We don’t have original standing stones or Pictish carvings in our archives, but these mean we can host a snapshot of information about these unique artefacts. The original historic sites may already be lost, or are vulnerable for a multitude of reasons – but we have captured their data in the Squeezes.

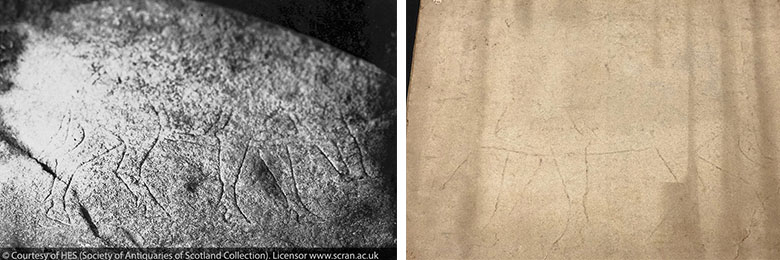

On the left, a photo of the original Dunadd Boar carving at Dunadd Fort. On the right, the Dunadd Boar squeeze in the HES archive collection.

Thinking outside the box

With this new information, how do we now do our job of taking care of the Squeezes?

We now know their protruding shapes are vital to the information they hold. We understand that they must not be flattened or squashed. Solutions to this proved difficult as our archive primarily stores things stacked flat or rolled, as we house many architectural blueprints and other “smooth” items.

The hunt for archival boxes in our supply store began, but what could possibly accommodate such unusual shapes without taking up too much space?

Aha! Upon spotting a large pile of acid free plastazote in the room, inspiration struck. Plastazote is an archival quality, acid free foam. Using the deepest boxes we could find, we began padding them out with the plastazote, creating cosy cushions for the squeezes to lie on.

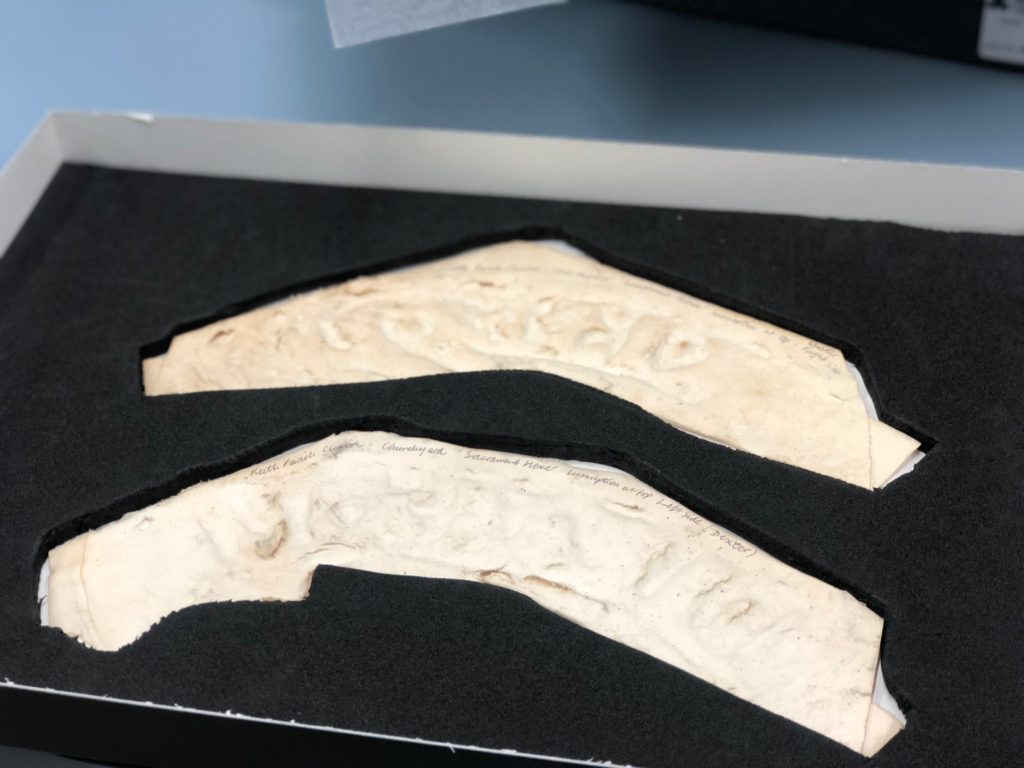

Then came the tricky part: I began the task of studying each squeeze’s shape individually, layering up the plastazote with the shape of a squeeze cut into the centre. When there were enough layers for the squeeze to sit in a tailored well of its own shape, I placed another whole piece of plastazote on top, and began layering for the shape of a different squeeze. This way the squeezes were stacked, but had spacious beds that would not press them out of shape.

Squeezes in their new boxes, in the HES archives collection. The squeezes show inscriptions from a Medieval sacrament house.

The Lesson of the Squeeze

So what did the Squeezes teach me? Above all, it taught me that it is okay to not know how you are going to do something. It’s exciting even! Just start with the basic understandings. I am still learning about the Squeezes.

And so if you wish to tell us more about them, or would like to see the Squeezes for yourself (or any of our archival material for that matter), then you can contact our Archives Public Services team through archives@hes.scot, or take a look at our Archives and Research work on the HES website.