With some 10,250 miles of coastline and 790 islands, along with allies and trade links overseas, voyages across the sea have always been vital to Scotland’s people and places.

You’ll probably have heard about the famous journeys made by Flora MacDonald and Bonnie Prince Charlie, or the five-year-old Mary Queen of Scots escaping Dumbarton Castle on a ship to France.

This blog tells four lesser-known tales of adventure, tragedy and discovery associated with the romance and perils of setting sail. All aboard!

The Miraculous Voyage of Betty Mouat

134 years ago this month, on Saturday 30 January 1886, 59-year-old Betty Mouat set off on a voyage from her home near Sumburgh to Lerwick.

This was a common and unremarkable journey for Betty, who regularly travelled from the southern tip of Shetland to the capital to sell her knitted wares. Armed with a bottle of milk and two biscuits, Betty was the only passenger on the Columbine, which set off in clear, if not rather chilly, conditions.

Sumburgh, Shetland: home to Sumburgh Airport and Betty Mouat’s croft

Disaster struck when the Columbine hit heavy seas, causing the captain, James Jamieson, to fall overboard. When the remaining crew launched a desperate bid to save him, they too were washed away from the boat. Betty, sheltering below deck, knew little of the drama until she eventually struggled above deck. She found herself alone on the Columbine drifting away from Shetland.

For nine days, Betty drifted solo across the North Sea, hammered by storms and with only her milk and biscuits for sustenance. Eventually, and miraculously, the Columbine washed ashore on a beach near Ålesund, in Norway, narrowly avoiding numerous rocks and reefs. Betty’s voyage should have lasted less than three hours.

The beach where Betty was washed ashore is called Colombinebukta, after the ship (Fotoagelias, Creative Commons)

Betty immediately became a celebrity in Britain and beyond, inspiring headlines in newspapers as far away as the New York Herald. Queen Victoria herself was so touched by the story she requested a cheque for £20 be sent from Windsor Castle to Betty’s croft.

Fame did not go to Betty’s head. After a hero’s welcome back in Shetland, she returned to Sumburgh and lived to the grand age of 93 – presumably with her feet firmly on dry land.

The Extraordinary Story of Isobel Gunn

Our next voyage begins in June 1806 when John Fubbister of Tankerness, Orkney, boarded a ship in Stromness bound for the wilderness of western Canada.

It was not unusual at the time for Scottish men to emigrate to work in the arduous fur-trapping trade. But this voyage is remarkable for one simple fact: John Fubbister was a woman in disguise.

Stromness, where Isobel Gunn’s remarkable journey began (Geoff Wong, Creative Commons)

Nobody is quite sure why Isobel Gunn assumed her father’s identity in order to join the all-male Hudson’s Bay Company. Some claim she was enticed by her brother’s tales of adventure, romantics say she was following a lover. She may simply have been motivated by the £8 annual salary. Either way, Isobel defied the rules and became the first white European women to step into the Canadian wilds.

Incredibly, Isobel’s disguise worked for at least a year. She more than matched her male colleagues in the back-breaking physical labour, earning a pay rise and trekking 1,800km from Fort Albany to North Dakota.

Hudson’s Bay Company employees travelling through Canada, 1825 (Peter Rindisbacher, Public domain)

A Dramatic Discovery

Then, on December 29, 1807, Isobel requested leave from work. Her boss, Alexander Henry, wrote in his journal:

An extraordinary affair occurred this morning. One of the Orkney lads, apparently indisposed, had requested me to allow him to remain in my house for a short time.”

Isobel had been hiding a pregnancy. Astoundingly, it was not until she gave birth in Henry’s front room that her ruse was finally discovered. Henry wrote of returning home to find:

A poor, helpless, abandoned wretch, who was not of the sex I had supposed, but an unfortunate Orkney girl, pregnant and actually in childbirth.”

A healthy boy, James, was delivered safely. Isobel named a fellow Orcadian, John Scarth, as the baby’s father. Despite travelling with Isobel from Stromness, records suggest Scarth only discovered her true identity by chance when he returned to their cabin after an evening of drinking. Isobel claimed that he had raped her.

Isobel was ordered to leave the Hudson Bay Company and began the return voyage to Orkney on September 20, 1809. She died, reportedly penniless, in 1861 at the age of 81.

The Tragedy of The Maid of Norway

When Alexander III died falling from his horse in March 1286, he left no surviving children. After much dispute and deliberation his Norwegian-born granddaughter, Margaret, was named Queen of Scotland.

A stained glass depiction of the Maid of Norway in Lerwick Town Hall, Shetland

The “Maid of Norway” was just seven years old when she set off on a voyage from Bergen to Scotland in order to ascend the throne. Tragically, Margaret never reached her destination.

After the Queen fell ill mid-voyage, her ship landed in Orkney around 23 September 1290. There, a few days later, Margaret died, possibly from food poisoning or the effects of seasickness. Her body was returned to Norway and buried in Bergen, while Scotland was plunged into a succession crisis.

The story takes a curious turn when, ten years later, a mysterious woman appeared in Bergen claiming Margaret’s identity and maintained that she had in fact not died in Orkney, but had been sent to Germany.

She attracted support from the people of Bergen and some members of the clergy, despite appearing to be at least 40 years old when the real Margaret would have been just 17.

But King Haakon V was having none of it. In 1301, he had “the False Margaret” burnt at the stake and beheaded her husband. Tales of a “betrayed princess” entered Norwegian folklore and a small chapel was built on the execution site.

The Real-Life Robinson Crusoe

Above the entrance to one of the cottages on the main street of Lower Largo in Fife stands a statue of Scotland’s most famous castaway.

The statue was erected in the picturesque fishing village in 1885, some 190 years after local shoemaker’s son Alexander Selkirk first ran away to sea. Records from August 1695 suggest that Selkirk was fleeing punishment after being accused of “indecent carriage in church.”

A local poses under the statue of Alexander Selkirk, erected at his former home in 1885 (© Courtesy of HES, Francis M Chrystal Collection)

By 1703, Selkirk was an experienced sailor and master on board the privateer Cinque Ports. His notorious voyage began on 11 September that year. The Cinque Ports, accompanied by the George, left Kinsale for the coast of Central and South America.

Five months of privateering later, after a fall out between the two captains, the ships went their separate ways. Selkirk remained on the Cinque Ports with Captain Thomas Stradling, a man Selkirk did not see eye to eye with.

During a stop at the Juan Fernandez islands, 416 miles off Chile, Selkirk’s resentment of Stradling grew. He became convinced that their ship wasn’t seaworthy. Rather than continue on the voyage, he elected to be left alone on an uninhabited island.

Selkirk disembarked with “his Clothes and Bedding, with a Firelock, some Powder, Bullets, and Tobacco, a Hatchet, a Knife, a Kettle, a Bible, some practical Pieces, and his Mathematical Instruments and Books.” He waved a hearty farewell to the Cinque Ports – before immediately realising his mistake.

The island Alexander Selkirk was left on, now called Robinson Crusoe Island (Serpentus, Creative Commons)

Castaway

Selkirk remained on the island for four years and four months, surviving by building two huts, hunting goats and keeping a daily routine of religious exercises. On 2 February 1709 he was finally rescued by a vessel called the Duke. The crew discovered “a Man cloth’d in Goat-Skins…who had so much forgot his Language for want of Use.”

Appointed as mate on the Duke, Selkirk continued his epic circumnavigation of the globe. He returned to Britain in October 1711 after a whopping eight years – half spent in total isolation.

Selkirk’s amazing story won him fame, but not fortune. He returned to Fife for some years, where he built a cave in his father’s garden and lived as a recluse. By 1721 he was back at sea for the last time. He died of disease while chasing pirates on the HMS Weymouth.

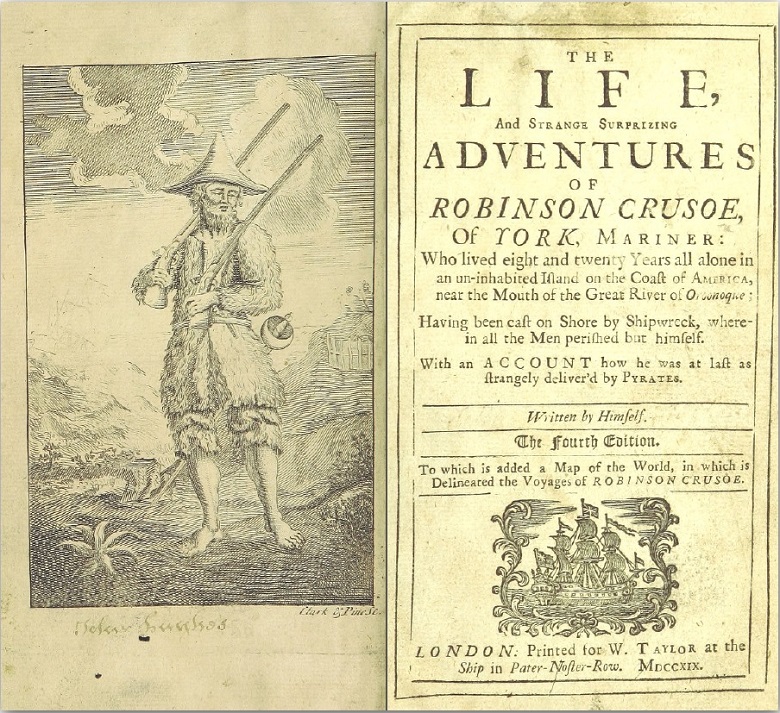

Alexander Selkirk’s experience inspired Daniel Defoe to write ‘Robinson Crusoe’ (The British Library, Public domain)

Selkirk lives on through the pages of Daniel Defoe’s world-famous novel Robinson Crusoe (1719). The classic castaway story, one of the best-selling books in history, is based on Selkirk’s life. His island home was renamed Robinson Crusoe Island in 1966.

And of the Cinque Ports? Selkirk’s suspicions were justified. It sank off the coast of Peru not long after leaving him behind.

A year of voyages…

Inspired by our ripping yarns? Want to take your own journey of discovery? Find a Historic Environment property or event taking part in Scotland’s Year of Coast and Waters.

Keep an eye out for more #YCW2020 blogs throughout the year. Alternatively, sign up to the HES blog to make sure you never miss a story!