The Steading is an extraordinary house that belonged to wood artist and furniture maker, Tim Stead, who died of leukaemia in 2000 aged only 48.

From the outside it resembles a fairly standard eighteenth century rural farmhouse and outbuildings. But a closer look reveals little clues: a lead-encased axehead bas-relief confronts you at the entrance to the Steading; windows are not the usual shape. A door is hung with dozens of ancient keys, a rusting collage.

A world of wood

But these are simply intimations. Entry through a small dark hallway leads into a riot of gleaming woods whose sculptured surfaces completely encase the interior.

Floors, walls, stairs, fireplace, doors, cupboards, grandfather clock, sunroom, four-poster beds that ripple like a surrealist chess set or evoke the brochs of northern Scotland.

Everything is a wooden sculpture.

The eye of a sculptor

Stead first studied at Nottingham Polytechnic, divorcing himself from the fashionable zeitgeist of conceptual art.

From Nottingham, he went to Glasgow School of Art and started making the massive, sculptural pieces of furniture for which he is best known.

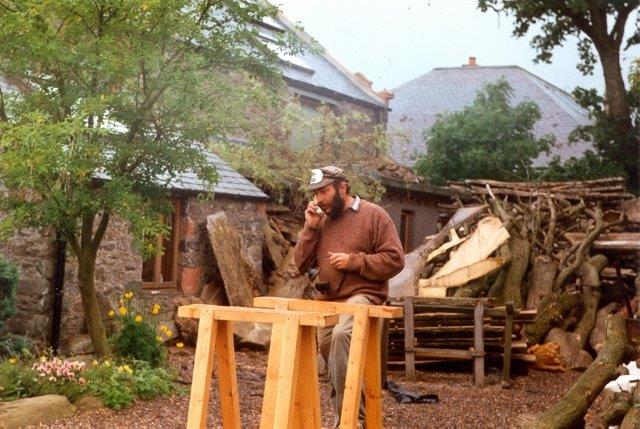

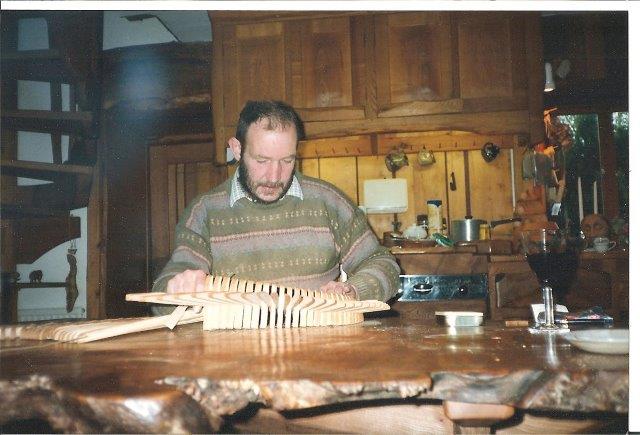

Tim Stead in 1986

Unlike other designers of the 1970s who favoured crisp straight lines, Stead worked wood with the eye of a sculptor, and of someone who knew how to make solid wood supremely comfortable.

Cafés and chapels: Pushing boundaries

Regulars to the iconic Café Gandolfi in Glasgow know this. He exploited the grain and the texture both inside and outside the timber, always revelling in the excitement of exploring what he might find in every tree trunk.

Tim Stead at work outside his home

All the time, though, he was sculpting and exploring the boundaries of what could be done with wood.

Public pieces such as the massive Piper Alpha memorial chapel in Aberdeen, furnished entirely by Stead’s own hands, exposed his infectious style. Like Rennie Mackintosh, he spawned a whole generation of artists.

The Steading: A life’s work

The Steading, bought in the 1980s, was a blank canvas for Stead whose life’s work it became to extend the house and work on the interior. He added new elements over a period of 20 years.

By the time of his early death the whole building was clad in his work. From a wooden basin in the bathroom to tiny cupboards concealing ugly fuse boxes, or from drawers hidden in the treads of the stairs to massive four-poster beds, everything is a unique sculpture.

There are around fifteen doors in The Steading: each one is different.

Making the A-List

The Tim Stead Trust was formed to raise funds to buy The Steading so that it can continue to be shared with the nation. But, just as Stead’s work would never fit comfortably into any sort of pigeon-hole, The Steading has proved difficult to categorise with funding bodies. Is it art? Is it heritage?

The Steading is both, and the Trust is delighted that Historic Environment Scotland has deemed it worthy of A-listing, making the salient point that Tim Stead’s interior has an extra feature not seen in the houses of other artists and architects.

Citing, amongst others, Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Hill House, or Basil Spence’s house and studio in Beaulieu, they point out that “in these examples the architects designed these interiors but did not build them.” Tim Stead did both.

This acknowledgement has come as a welcome vindication to the Trust, which now hopes that funding will be forthcoming, either from public or private funders.

There is not much time; the house goes on the market in April. A video of the house and all information can be found on the Trust’s website.

About the Author

Nichola Fletcher, Chair of the Tim Stead Trust, is a designer and maker working in precious metals and rare materials. A close friend of Tim and Maggy Stead’s, she shared exhibitions in Luxemburg and Sweden and she and her husband commissioned many pieces from Stead over the years. Nichola is also an award-winning food writer.