2020 marks the 700th anniversary of one of Scotland’s most famous historical documents, the Declaration of Arbroath.

The Declaration, which historians acknowledge as one of the most eloquent expressions of national identity to survive from medieval Europe, was in fact a letter written in the name of 39 Scottish nobles, to Pope John XXII, living at that time in Avignon, France.

A 2020 facsimile of the Declaration of Arbroath created by the National Records of Scotland

From Newbattle to Arbroath

The ‘Declaration’ was one of a group of letters composed by King Robert’s counsellors in response to the king’s excommunication in 1318, which argued forcefully for papal recognition of Scotland’s independent status and Robert’s right to rule.

The letter is dated 6 April 1320 at Arbroath Abbey, but historians now recognise that the nobles were gathered not there but at a ‘general council’ held at Newbattle Abbey south of Edinburgh.

The king’s chancellor, Abbot Bernard of Arbroath, took the Declaration and other documents back to his home abbey after the council, where he completed their production.

The Presbytery at Arbroath Abbey

The people of the declaration: the earls

King Robert and his advisors, who wanted to convey the sense of overwhelming support for the king on the part of the noble community, assembled the largest and most prestigious group of lords they could muster.

The most prestigious group of all was the earls, an impressive eight of whom come top of the list in the letter. These included the three traditionally most powerful earls – Fife, March, and Strathearn, and a newcomer, as King Robert had created a massive new earldom of Moray for his right-hand man, Thomas Randolph.

A memorial panel on the exterior of Edinburgh Castle commemorating Thomas Randolph, Earl of Moray

Also mentioned were the earls of Lennox, Ross, Caithness and Sutherland. These last two most northern earls may not have actually attended the council at Newbattle in person, given that they fail to witness a single surviving charter of King Robert. Their seals may have been obtained in their absence.

While this all looks impressive, there were in fact a number of high-profile earls missing, namely the earl of Angus, the Englishman Gilbert de Umfraville, as well as King Robert’s nephews Earl Donald of Mar and Earl David Strathbogie of Atholl, who had thrown in their lot with King Edward II of England.

Their absence is the first hint that the Declaration was in fact papering over some serious fault lines in the Scottish political community.

King Robert’s friends

With the exception of the new earl of Moray, King Robert relied much less on the earls for military and political support than a separate group of nobles, most of whom also are named in the Declaration.

James Douglas portrayed by Aaron Taylor-Johnson in the Bruce biopic Outlaw King (2018)

Some of these men had honorific offices in the royal household, for example Walter Stewart, the steward, Gilbert Hay, the constable, and Robert Keith, the marischal.

While these men already held a certain level of prestige in the political community, the king was busy laying new lands and privileges on another close ally, James Douglas.

Indeed, Robert bestowed the town, castle and forest of Jedburgh on ‘The Good Sir James’ at the same Newbattle general council where the Declaration was written (or at least agreed upon). It would be James who would later carry Robert’s heart to Spain and into battle with the Saracens.

A stone at Melrose Abbey, designed by Victoria Oswald in 1998, marks the possible burial place of Bruce’s heart

King Robert’s enemies

The list of 39 nobles opening the Declaration is composed in order of the prestige of each earl or baron, and may have described the physical order in which they were arranged at the general council.

If this was the case, the positioning of Bruce’s closest friends cheek-by-jowl with men who would soon prove to be his greatest enemies can only have been a deliberate choice.

These men included the Butler of Scotland, William Soulis, who was placed between perhaps the king’s most prominent allies, Walter Stewart and James Douglas. Soulis would give his name to the coup d’état (the Soulis Conspiracy) which would rock the kingdom only weeks after the sealing of the Declaration of Arbroath.

A statue of Robert the Bruce looking out from Stirling Castle

Between James Douglas and Bruce supporter John Menteith we find Roger Mowbray, David lord of Brechin, and Ingram de Umfraville, three men who were implicated in the failed coup.

At a parliament held at Scone that August, Soulis got away with imprisonment, but David Brechin and the body of the recently deceased Roger Mowbray were drawn by horses and beheaded, in probably the first time this kind of grisly political execution took place in Scotland.

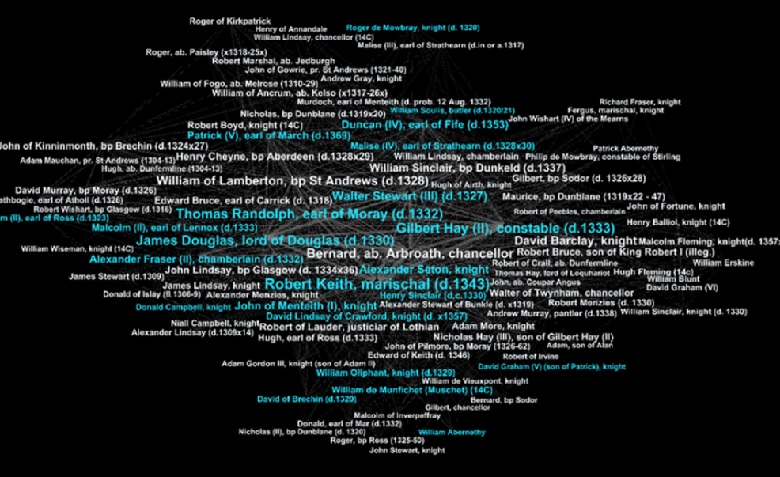

The social network of the 1320 nobles

As part of the Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded project The Community of the Realm in Scotland, 1249-1424: history, law and charters in a recreated kingdom, I have been exploring the social networks of the people of the Declaration.

As part of this project, the royal charters of King Robert I and his son David II have been entered into the People of Medieval Scotland database, where readers can explore the lives of the 1320 barons.

Using specialist social network analysis software, I have graphed the 99 witnesses to King Robert’s charters: those who witness more often together take a more prominent place in the graph above.

The nobles of the Declaration are highlighted in blue. We can see that Robert’s closest allies – Randolph, Stewart, Douglas, Keith, and Hay – are the most central laymen in the network. (The other most central figures were churchmen).

Furthermore, while Robert’s enemies who set their seals to the 1320 letter are part of the network, men like Roger Mowbray, William Soulis, and David Brechin appear very much on its fringes.

You can learn much more about this network on the project website.

Dr Matthew Hammond is a Research Fellow at King’s College London