It was about week two of the Covid-19 lockdown when I first picked up my knitting needles. A skill I’d learnt many years ago in school, I hadn’t tried knitting since then. But the search for an affordable yet rewarding hobby led me to knitting, and I quickly remembered how addictive the pastime is.

The time it gives for contemplation, as I therapeutically knit back-and-forth making an ever-growing scarf (you’ve got to start somewhere!), is something I particularly enjoy. It led me to consider the origins of knitting, in particular within Scotland, and delve into the HES Archives to unearth some treasures!

“A girl knitting”, by Philippe Mercier in the 18th century, which is part of our collections at Duff House. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

The origins of knitting

Knitting as a means for making clothes and accessories can be traced back to the Middle East possibly as far back as the 5th century. Fundamentally, it involves using long needles to loop material (often wool) into a series of interconnected loops, which then forms a fabric.

The type we are more often familiar with is ‘flat knitting’, which involves using two needles. ‘Knitting in the round’ is another technique that requires four or five needs to create a continuous tube, often to make things such as hats and stockings.

Early knitting examples were sometimes made of cotton, unlike as opposed to the wool or yarn we associate with knitting today.

It wasn’t until around the 14th century that knitting reached Europe.

This hand knitted blue bonnet belonged to Thomas Guthrie of Scroggerfield (1746-1820). © National Museums Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Knitting in Scotland

The art reached Scotland in the 15th century and quickly became the means of earning a living for many. Some of the earliest records of the trade show the formation of a trade guild in 1496 by Dundee bonnet makers.

One of their significant outputs were knitted caps, like the one above, which had the fibres ‘felted’ together to make them waterproof. These caps were imitations of the velvet caps reserved for the upper classes. They were known as ‘blue bonnets’ and were common work-wear for Scottish labourers.

The design varied between the Highlands and Lowlands, as did its popularity over the centuries. Interestingly, in the way many view tartan today as quintessentially Scottish, it was the blue bonnet that represented the nation in the 18th century.

This hosiery factory in Strathaven was still producing goods in the 1970s, despite competition from larger firms.

Industry and Trade

In the early days of knitting in Scotland, it was very male dominated. What we now consider a quarantine hobby was seen as a highly skilled trade, done by trained craftsmen belonging to guilds or incorporations.

However, by the 17th and 18th centuries knitting was a flourishing trade in Scotland and a key occupation for many; women, children and men. They produced everything from jumpers to gloves to underwear.

Some products were even exported overseas or traded with passing merchant vessels. For example, some in Shetland traded their knitwares with passing Dutch ships for resources including tea and sugar. In 1793, Aberdeen exported around 76,000 dozen pairs of hand-knitted stocking. This was primarily to the Netherlands.

In 1589, the first knitting machine was produced in England by William Lee. This was a stocking frame, and marked the beginning of ‘framework knitting’. It made knitting up to twelve times faster. The knitter operated the machine through a variety of hand movements and a foot peddle.

Machine knitting soon spread to Scotland. The New Mills Woollen Factory in Haddington, East Lothian, was founded in 1681. It is seen as the first serious venture into establishing framework knitting in Scotland.

A 1974 photograph of the now demolished Wilton Mills, a woolen mill owned by Dicksons and Laings in Hawick.

From the Borders to the Islands

Small-scale knitting machines also began to make it into homes. By the 19th century, knitting factories were growing in popularity, and technology and machines developed further. Hawick had become the Scottish centre for machine-knitted goods, as handknitting became less commercially sustainable. Other knitting factories appeared across the country.

Only Shetland remained handknitting regularly on a commercial basis. They had two dominant types of knitting at this time: the well-known Fair Isle style, and a lace knitting approach used for making shawls.

This practice continues to this day, and its output has an international reputation. Knitting remains important for Shetland – all primary school children are taught the art.

Children continue the practice of hand-knitting to this day in Shetland. © National Museums Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Design focus: Regional Knits

Regional varieties of knitting developed all over Scotland.

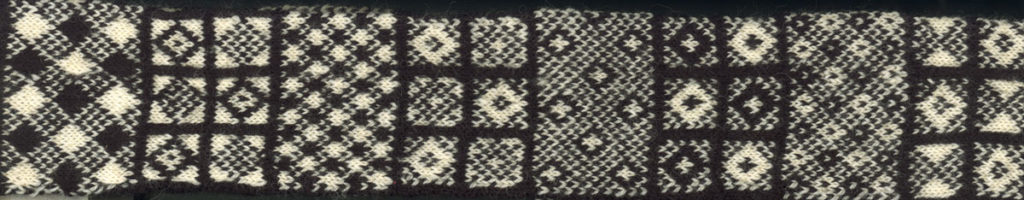

One prominent example is the Sanquhar Knitting, developed in the Ayrshire village of Sanquhar in the 18th century. The individual Sanquhar ‘patterns’, such as the Duke and the Rose, were often passed down through word of mouth from generation to generation. Some still continue this oral history tradition today.

Examples of Sanquhar-style knitted patterns including Duke, Rose and Shepherd’s Plaid. © National Museums Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

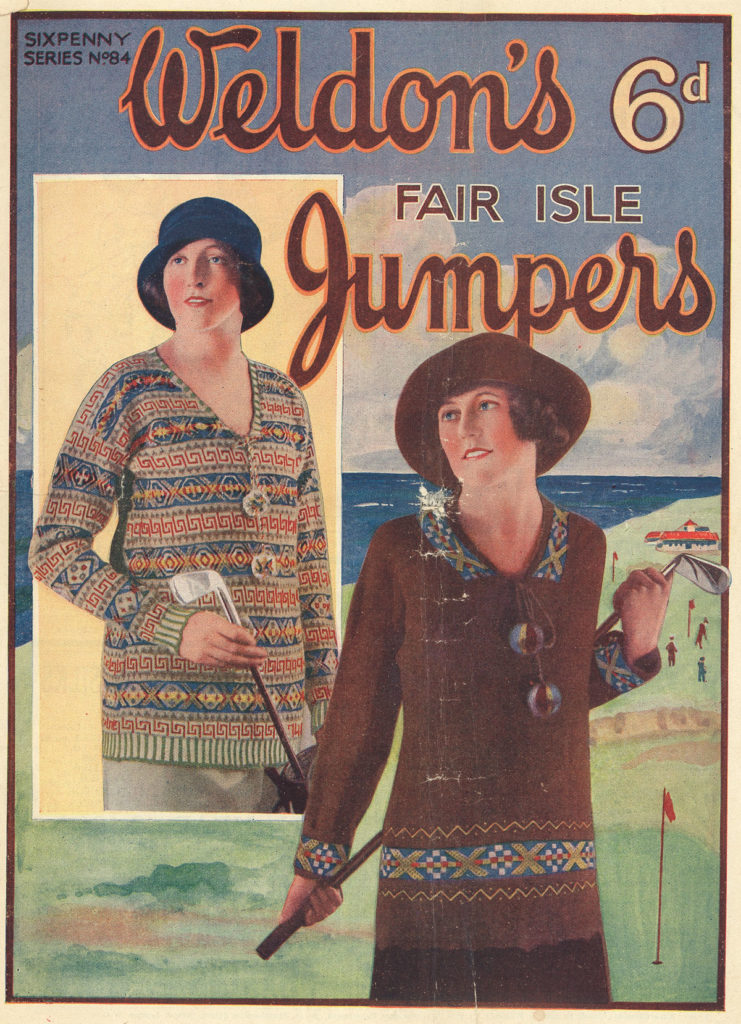

Another regional variety is the Fair Isle design. It originated on the island of Fair Isle, which lies between the Orkney and Shetland Islands (though part of Shetland). The inspiration for the patterns and colours is unknown, though it is probable that a knitted item with a similar pattern was traded onto the island, and acted as a springboard for this design.

This knitting pattern booklet by Weldon’s of London shows the popularity of Fair Isle knitting in the 1930s. © Scottish Life Archive. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Fair Isle experienced a surge of popularity in the 1920s, partly due to Prince of Wales wearing a sweater as part of his golfing clothes.

Throughout the 20th century it experienced periods of popularity and is now one of the most well-known patterns for knitware in the world. Today, it’s also a source of inspiration for the fashion industry.

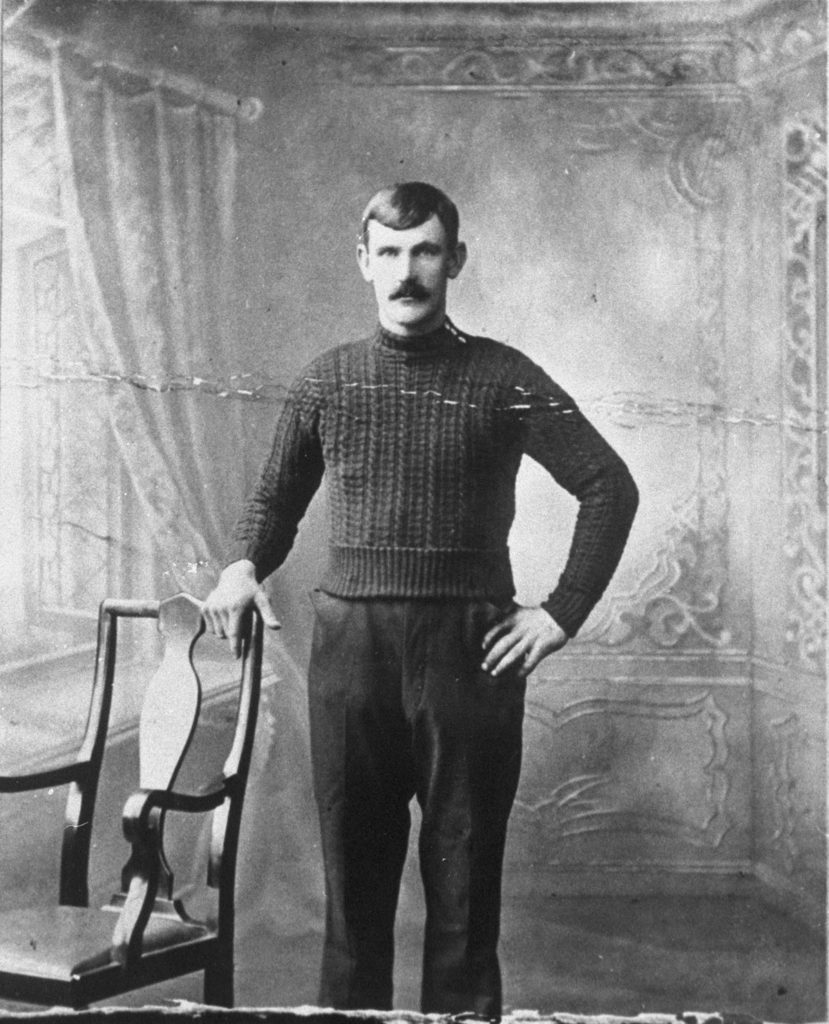

In this late 1800s photograph of Mr Banks from Musselburgh, you can see a gansey jumper. They were characteristic of fishermen’s clothes until the First World War. © National Museums Scotland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

The Fishing Communities

Knitting was a popular practice amongst women in Scottish fishing communities, particularly on the east coast. Many women made knitted jumpers for the fishermen during the 18th century. These are often known as ‘gansey’ jumpers and were traditionally dark blue and tight-fitting for warmth.

As their popularity spread, different patterns developed. It is said that each community had their own pattern and individual styles, and the knitted jumpers could be used to identify deceased fishermen in the event of an accident. Recent academia challenges this notion, but it’s an interesting possibility!

Look closely at this 1866 photograph of a woman at Melrose Abbey from the HES Archives and see if you can spot her knitting needles.

A popular pastime and domestic practice

From the 1830s, knitting became a fashionable hobby for Scottish women.

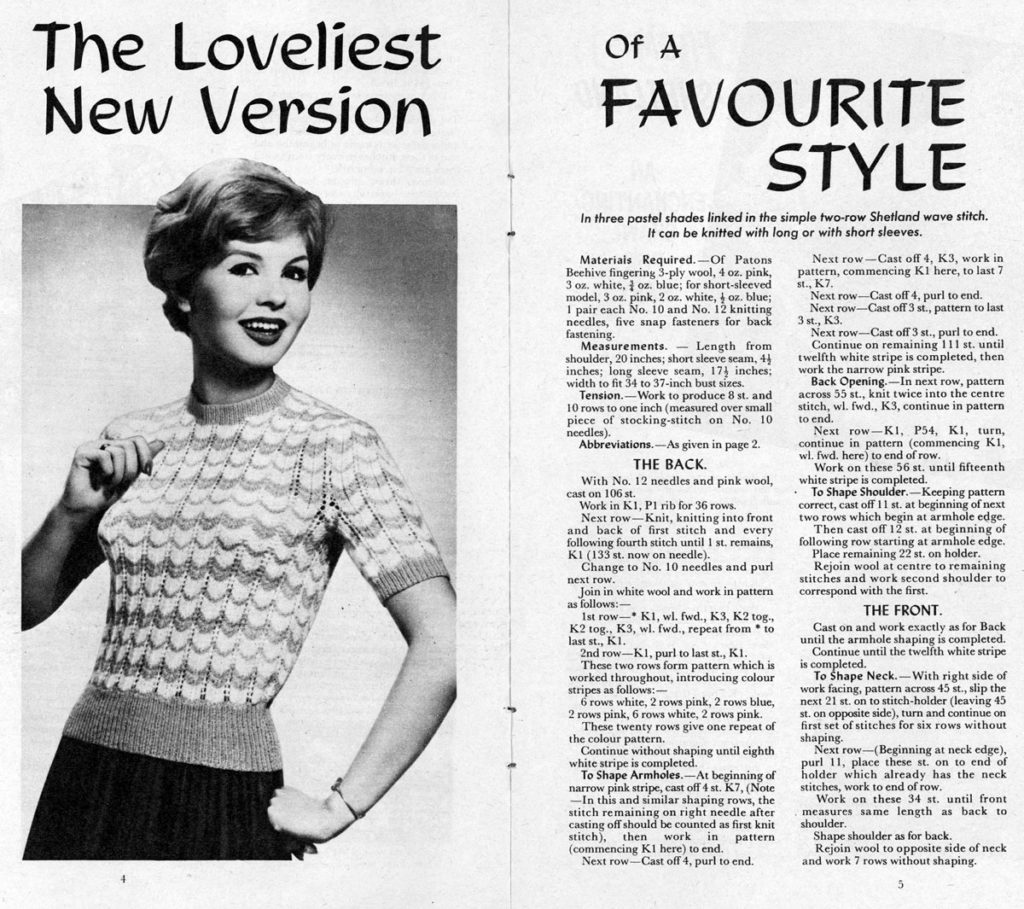

Knitting books, and the sharing of knitting patterns, grew in popularity from the mid-1830s. Particularly sought after were the Fair Isle designs and interpretations. This example is taken from a People’s Friend book in the late 1950s – fancy giving it a go?

This page from a People’s Friend knitting book, dates to the late 1950s, over a hundred years after the first knitting ‘recipes’! © Shetland Museum & Archives. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Knitting today

The act of handknitting has become more of a hobby than a necessity to produce clothing, as machines have taken over much of the knitting industry. However, some do continue the handknitting tradition.

Many take advantage of the variety of Scottish wool on offer, from the thick Arran yarn, to the wool produced from the North Ronaldsay sheep on Orkney. We are lucky to have such a variety of material of knitting, with varying textures and possibilities, here in Scotland.

Knitting can be an expression of style and taste, or a chance to make something different. Some talented individuals are able to make seemingly anything through knitting – have a look at this amazing rendition of James V by Stirling Castle Steward, Tricia Golledge. Have you ever tried to make, or are in the process of making, any historical figures? Share them with us on social media and tag us in!

…knitted a James V. He might not be historically correct – hes made of mix of knitting patterns – Bonnie Prince Charlie, Rabbie Burns, GrandPaw Broon. pic.twitter.com/wqp8ReYk42

— Tricia (McKeown) Golledge (@triciagolledge) April 17, 2020

If you’re an experienced knitter looking for inspiration, have a look though the archives to see if you can complete any historical patterns – we’d love to see what you produce!

Hopefully you’ve enjoyed delving into our archives, and maybe even been inspired to take up this pastime. All that’s left to say is, #StayAtHome and get knitting!