Sewing machines have always been a big part of my life, as my mum is a trained dressmaker. Sometimes it seems insufficient to call her a ‘dressmaker’ or ‘seamstress’ because in my mind she’s nothing short of a sewing wizard!

I felt like the luckiest child in the world growing up. I could choose to be whatever princess, animal or character I wanted, and my mum would be able to make the costume for me. Some of my fondest memories of early childhood are trips to Fiona Nicoll’s dressmaking shop in Falkirk where she used to work.

I can still hear the machines humming, scissors snipping, the smell and touch of fabric, and the ferocious strength of the button-making machine. I always remember the sense of community amongst the group of seamstresses who worked there, whizzing away at their machines in between chats and cups of tea.

A bit of sewing history

Despite my early associations of sewing exclusively involving women, the industry actually started life in a very male dominated way.

Before the Industrial Revolution clanged and steamrolled its way across the developed world, both men and women had been sewing by hand for over 20,000 years.

People originally did hand sewing using bone needles. Image © National Museums Scotland, licensed by scran.ac.uk

The first needles were made from animal bone or wood, and animal sinew was used as thread. Over the years the materials used to make needles were updated to carbon steel or nickel with cotton thread, but hand sewing was still the primary means of stitching up until the mid-1700s.

By that time, hand-sewing had become more associated with women – but there’s a long list of men attached to the labour saving invention of the sewing machine.

The inventors

There is a lot of debate about who ‘originally’ invented the sewing machine, since the device didn’t come from one design. It’s the culmination of a half-century worth of invention.

- Charles Wiesenthal came up with the idea of a mechanised needle in 1755, but we don’t know if he took his invention any further than design concept.

- Thomas Saint, a cabinet maker, invented but didn’t patent a sewing machine in the late 1700s.

- Barthelemy Thimonnie developed a machine that allowed users to hook a needle and thread creating a chain stitch, patented in 1830.

It wasn’t until 1844 that a recognisable sewing machine was developed and built by the English inventor John Fisher. Fisher’s design was emulated by others including Elias Howe, who went on to invent the lockstitch (where thread can be looped on the reverse and a second thread looped through, securing the stitch).

The most famous name of all in the world of sewing machines though, is probably American inventor Isaac Merrit Singer.

Singer No.1 Sewing Machine © West Dunbartonshire Council. Licensed by scran.ac.uk

Singer created a machine very similar to Fisher and Howe’s in 1851. But due to the intricacies of patency law (and an error in the filing of Fisher’s patent) Singer’s cast iron model, with a foot pedal and an up-and-down needle, was recognised first.

The Clydebank Singer sewing machine factory

Despite coming to an agreement to share the patent and royalties, Singer went on to dominate the world of sewing machine production. Nowhere was this felt more clearly than in Scotland where the world’s largest Singer sewing machine factory was built in Kilbowie, Clydebank.

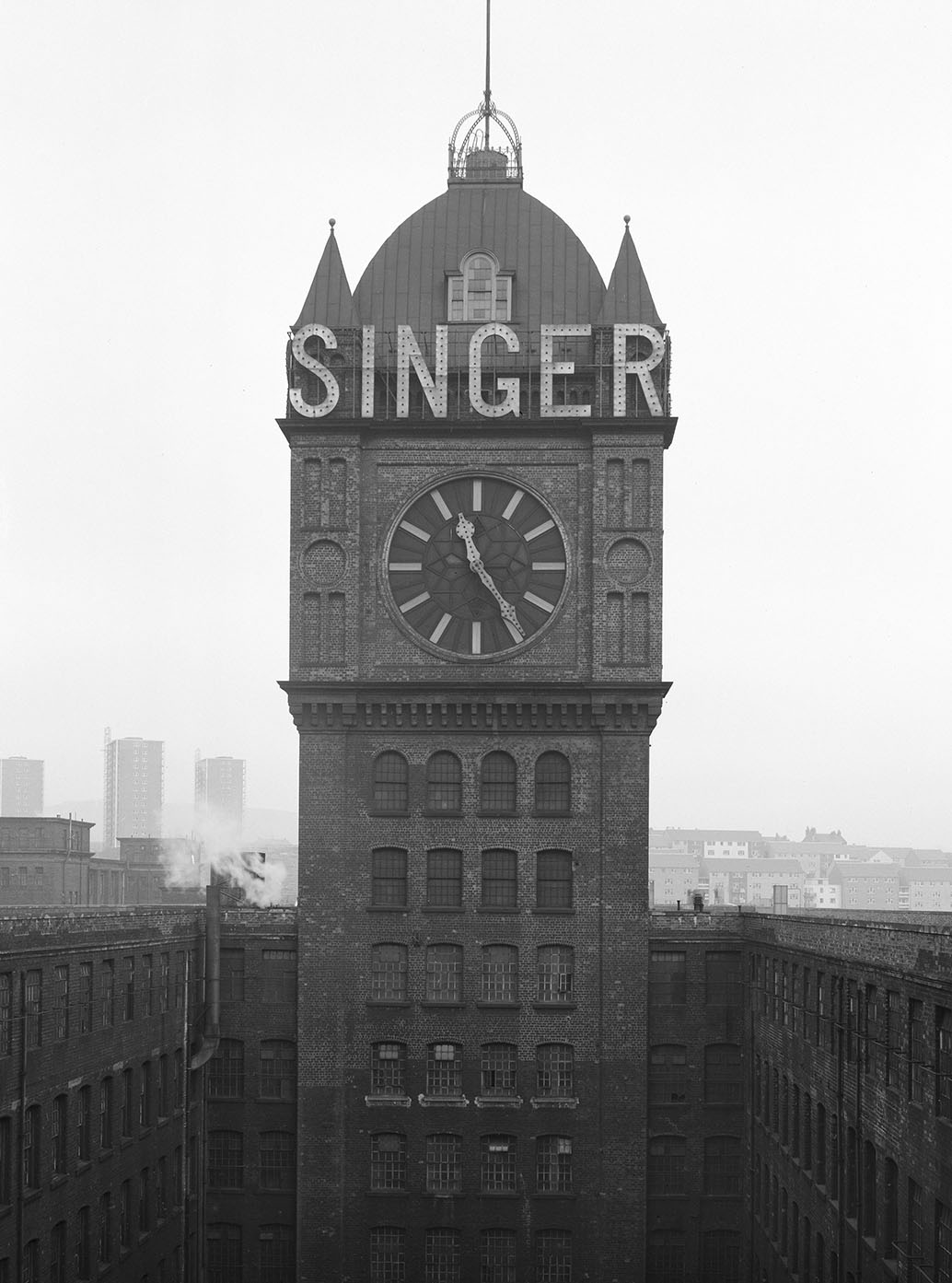

Construction of the Clydebank factory began in 1882, overseen by George McKenzie. The complex was huge, with two main buildings (one for domestic and one for industrial sewing machine production) three storeys high. A 200 foot central tower with the iconic ‘Singer’ name dominated the surrounding landscape. This tower was recognised as the largest four-face clock tower in the world.

Clock-tower at Singer’s Sewing Machine Factory, Clydebank. © Crown Copyright: HES (Scottish National Buildings Record)

There were also up to four miles of railway line laid out through the factory to connect the different buildings. The railway lines also connected to nearby stations Dumbarton and Helensburgh to assist with the shipping of goods.

Aerial photograph of Singer Sewing Machine Factory in 1934, showing transport links © HES (Aerofilms Collection).

The factory was later extended further to meet ever increasing demands. Two storeys were added, along with power station and sawmills. It was finally completed in 1885.

Open for Business

When it opened, the factory employed over 3,500 people and produced an average of 8,000 sewing machines a week. Though these machines were mass-produced, they were still made from solid cast iron, in an iconic elaborate Singer design, with flakes of nickel and gold interwoven on the exterior.

By the early 1900s the Singer Factory was responsible for the production of nearly 1.5 million sewing machines distributed across the world.

Singer Sewing Machine © Malcolm McCurrach

But though the factory provided a huge amount of employment, there were underlying problems with exploitation of the predominantly female workforce. In 1911, frustrated by increasing workload and decreasing pay, the majority of the 11,500 employees of the factory went on the ‘Singer Strike’.

Although ultimately unsuccessful, the strike action was a key event in the formation of Red Clydeside.

Singer and the Second World War

During the Second World War, sewing machines were needed to make army uniforms, as well as for ‘make-do and mending’ by home sewers. But the factory also began to switch its operations by making munitions and aircraft parts.

In 1941, the ‘Clydebank Blitz’ saw heavy bombing batter Clydebank and the factory. Over 500 civilians were killed, 39 of whom were Singer workers.

Bombed houses in Kilbowie Road during WWII © Newsquest (Herald & Times). Licensed by scran.ac.uk

Many Singer employees were also badly affected by the destruction of over 35,000 homes nearby due to the heavy bombing. The factory itself suffered severe damage that resulted in the loss of over 390,000 square feet of the factory. The famous ‘Singer’ clocktower was also badly damaged by fire when German bombs hit the nearby timber yard.

Modernisation

Although the town and factory suffered significant damage during WWII, they resumed full production quite quickly. However, towards the beginning of the 1960s, improvements in sewing machine design, including changing from cast iron to aluminium bodies which were also made at the factory, sparked the beginning of the end for the huge demand for the Singer sewing machine.

This happened at a time when there was a burgeoning Japanese market producing sewing machines in larger volumes for lower prices. Singer attempted to modernise their factory in the 1960s, but it was during this renovation the iconic ‘Singer’ tower – which had survived during the war – was demolished.

Workers leaving the Singer sewing machine factory, © The Scotsman Publications Ltd. Licensed by scran.ac.uk

This was symbolic for what was to happen to the factory itself. Sales didn’t recover, demand dropped, and the factory eventually closed in 1980. After over a hundred years of sewing machine production, the entire Singer sewing machine factory in Clydebank was demolished in the late 1990s.

Sewing Today

Though many businesses, home sewers and designers continued to work away at their machines, the downward trend in the popularity of the sewing machines continued into the 21st Century. Cheap, disposable garments mass produced in overseas factories have dominated our shops and wardrobes.

The majority of clothes made today end up in landfill, and the fashion industry is now the second biggest polluter on the planet. However, there is hope for our planet and our sewing machines as people develop a growing awareness of the monumental impact the fashion industry has on the environment.

There is a huge environmental, as well as financial, benefit in mending and recycling our clothes, and a fresh sewing machine market is developing. In addition, though the Covid-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact upon the world’s health and economy, it has increased the number of people taking up home-sewing to help make face-coverings and scrubs for essential workers and for personal use.

Lots of people are taking up sewing again – classes are available! © Malcolm McCurrach

The pandemic has also prompted big fashion houses to re-consider the necessity of presenting 4 runway shows a year in cities across the world, which would help cut travel as well as fashion waste. There has also been a surge in the popularity of programmes like The Great British Sewing Bee on BBC 1, encouraging non-professional sewers to try pattern challenges and transform old garments into something new. There are also many sewing classes available to teach people how to sew, and to re-engage a population with this traditional skill.

Continuing a family tradition

I am grateful to have inherited a wonderful Singer sewing machine from my mum on which, with her help, I’ve been trying to learn the art of sewing. I’m not quite ready to make costumes yet, but there’s something very satisfying about pressing my foot on the pedal and watching the needle stamp its way through the fabric.

Perhaps all the other vintage Singer sewing machines will come out from under café tables and shop displays and relive their glory days again as we come into a new age of awareness about the world in which we live.

I feel a remarkable sense of connection to the past when I hear the sound of my sewing machine. The mess of threads I make and all the pieces I sew the wrong way round remind me of a pleasant time in my childhood, and a hope for better things to come.