If you’ve passed along Lower Gilmore Place in Edinburgh recently, you may have spotted a powerful new addition to the urban landscape: a striking mural of African American freedom fighter Frederick Douglass.

Douglass stayed at 33 Gilmore Place during a two-year visit to Britain and Ireland in the mid-1840s, corresponding with fellow abolitionists and organising anti-slavery campaigns across Scotland. Last year, we unveiled a commemorative plaque at this significant address.

But Douglass’ work as “Scotland’s anti-slavery agent” was by no means confined to this corner of the capital. This blog explores the life and work of one of the most important African American voices in nineteenth century Scotland.

In September 2020, artist TrenchOne painted a mural of Frederick Douglass on the corner of Gilmore and Lower Gilmore Place

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey

Douglass was born into chattel slavery as Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. His exact date of birth at a Maryland plantation is unknown – the records of his former owner suggest February 1818. Douglass later adopted 14 February as his birthday, recalling his mother, Harriet, once calling him “Little Valentine.”

He was separated from his mother while still an infant. His maternal grandparents, Betsy, also an enslaved person and Isaac, who was free, raised him.

Aged six, he was moved to Wye House Plantation, where he spent around two years before being given to Thomas and Lucretia Auld. In turn, he was sent to Baltimore to serve Thomas’ brother, Hugh, and his wife, Sophia. Douglass considered himself lucky – the city was a far cry from working on a plantation.

“Knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom”

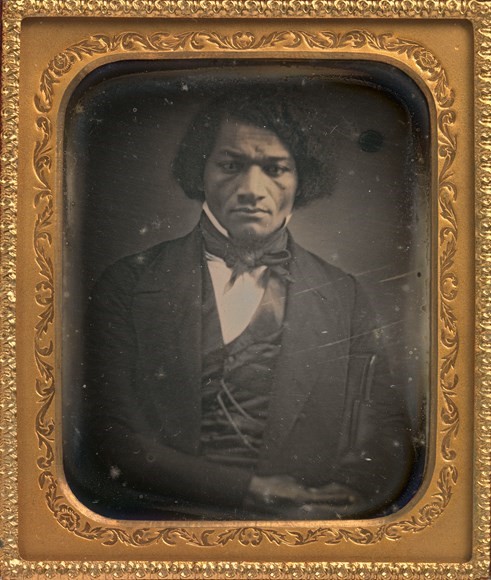

Frederick Douglass, Unidentified Artist, c. 1850 (© National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution)

From Douglass’ autobiography, we can glean that Lucretia and Sophia took a special interest in the young Frederick. The latter ensured he was well fed, clothed and tutored. In Douglass’ words she treated him “as she supposed one human being ought to treat another.”

Hugh Auld, however, did not approve. He was concerned that an education would encourage enslaved people to seek their freedom. With his books and lessons taken away, Douglass was forced to learn to read and write in secret.

Later, when he was hired out to a William Freeland, Douglass taught up to 40 of his fellow enslaved people to read at weekly Sunday schools. These lessons, too, were put to a stop by agitated slaveholders from neighbouring plantations.

But Douglass’ self-education had helped shape his views on human rights and freedom. He would later declare, “knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom”.

A New World

The house in New Bedford where the newly-married Frederick and Anna stayed with Nathan and Mary Johnson, and decided on the surname ‘Douglass’ (via Creative Commons)

Douglass stayed in the institution of slavery until 3 September 1838, when he risked his life for his freedom. He was inspired and supported by Anna Murray, a free Black woman who he had met in Baltimore and fallen in love with.

Disguised as a sailor, Douglass boarded a northbound train and travelled to a safe house in New York City via Delaware and Philadelphia. Upon reaching New York – and freedom – Douglass wrote:

“A new world had opened upon me…I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions.”

Murray followed Douglass north and by 15 September they were married. Their friend, Nathan Johnson, suggested Douglass as their married name. He’d been inspired by the surname of the characters in Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake – a first Scottish connection.

An 1839 engraving inspired by the second canto of ‘Lady of the Lake’ (© Courtesy of HES. Illustration in Views in Scotland)

Across the Atlantic

Settling in an abolitionist centre in Massachusetts, Douglass entered the world of campaigning, protesting and public speaking almost immediately. He became a licensed preacher in 1839, regularly appearing at abolitionist meetings and anti-slavery lectures. In September 1841, he was thrown off a train for refusing to sit in a segregated carriage.

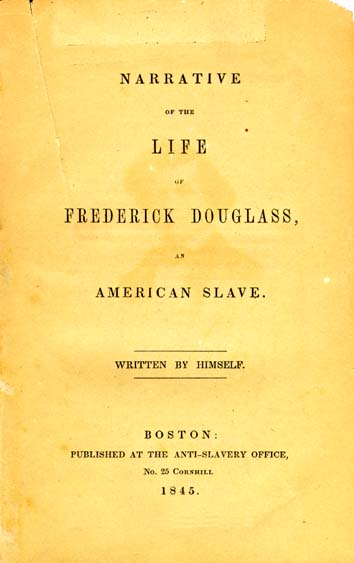

The title page of the 1845 edition of Douglass’ autobiography (Public Domain, via Creative Commons)

Douglass’ reputation grew further with the publication of his autobiography, so much so that he was encouraged to take a Transatlantic sojourn to prevent Hugh Auld from attempting to reclaim his “property”.

Douglass set sail for Liverpool in August 1845. He would go on to spend two years in Britain and Ireland, where he gained many supporters who campaigned for him to stay permanently. Funds were even raised to buy his legal freedom from Auld. Our focus, of course, is his time in Scotland.

An Edinburgh Sensation

Douglass made the first of numerous visits to Edinburgh in 1846. His writing tells us that he held the Capital in high esteem. He praised “architectural beauties” like the Scott Monument and “the Carlton Hill, Salysbury Crags and Arthur Seat” for giving Edinburgh “advantages over any city I have ever visited.”

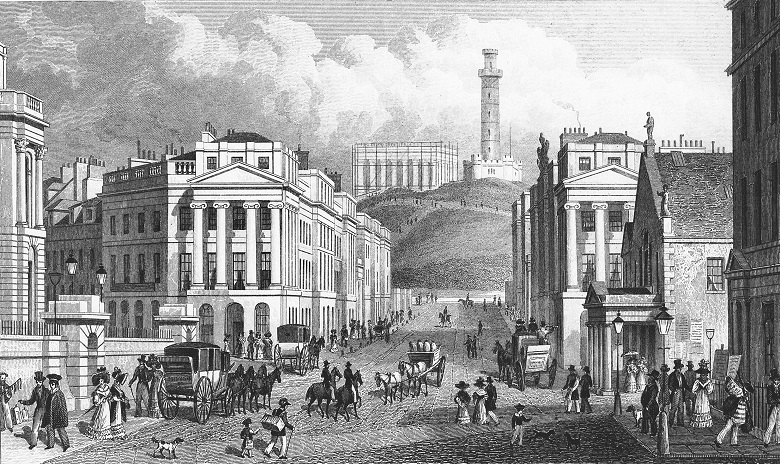

Waterloo Place, Edinburgh, as it appeared in the mid-1800s. Calton Hill is in the background. (© Courtesy of HES. Illustration from Modern Athens, T H Shepherd, 1829)

But Douglass was no tourist. Campaigning was first and foremost on his mind. Though he believed Edinburgh to be a racially enlightened city where he was “treated as a man, an equal brother,” there was plenty of work to be done.

Douglass spoke at venues across the city, drawing huge crowds. News coverage of lectures he gave at South College Street Church on 29 and 30 April 1846 reports that “this great building was crowded to suffocation in every part, by a highly respectable audience”.

The Assembly Rooms on George Street, 1829 (© Courtesy of HES. Illustration in Views in Scotland)

The following day, Douglass was guest of honour at a public breakfast in the Waterloo Rooms at 29 Waterloo Place. Later, he appeared in front of 2,000 listeners at the Assembly Rooms on George Street.

At both events, Douglass captivated the crowds with anecdotes from his time as an enslaved person, along with discussing the experiences of other African Americans. One was Madison Washington, who instigated an uprising on board a slave ship in 1841 (Douglass would later write a novella inspired by Washington entitled The Heroic Slave).

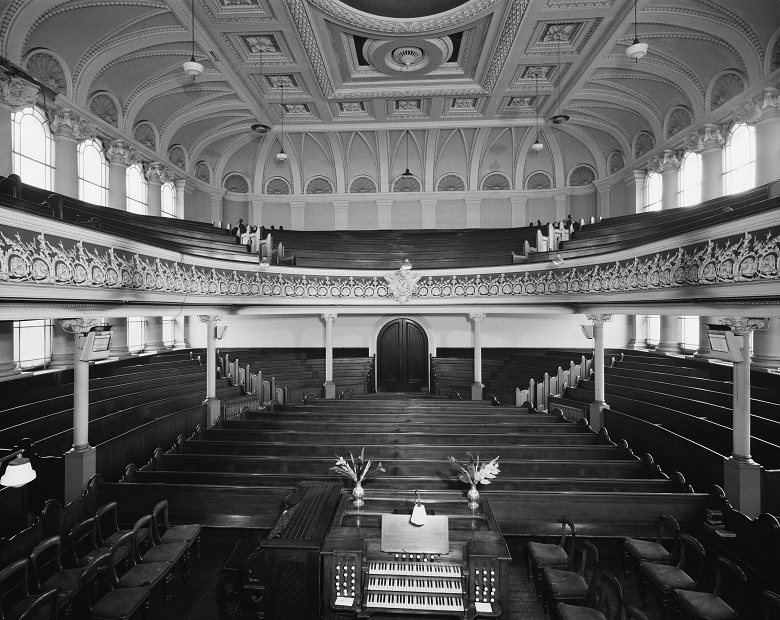

The music hall at the Assembly Rooms where Douglass spoke in 1846

Carvings on the Crags

One prominent Scottish issue that Douglass and his fellow abolitionists addressed was the Free Church of Scotland. Founded in 1843, this church obtained some of its funds from donations made by pro-slavery counterparts in the United States.

A campaign demanding that the Free Church cut these ties was in full flow while Douglass was in Edinburgh. He keenly lent his support, resulting in one of the more dramatic episodes during his time in Scotland.

The view across Edinburgh from Salisbury Crags

In May 1846, the campaign’s organiser, British social justice campaigner George Thompson, suggested that the slogan ‘Send Back the Money’ should be carved onto Salisbury Crags for all in the city to see.

According to a report in The Fife Herald from 21 May 1846, Mr Frederick Douglass, together with two ladies from the Society of Friends, immediately hurried up the hill “spade in hand” to do exactly that!

Having decided on “a spot in the vicinity of the Queen’s Drive” (the road around Arthur’s Seat was being constructed at the time), Douglass began to carve “in graceful characters.” This particular protest was short-lived. The story continues:

Information having reached the persons entrusted with the charge of the grounds, we understand that Mr Douglass was immediately taken to task…

…the philanthropic man of colour expressed deep contrition for the crime, and here the matter at present rests.”

Looking up at the prominent position the Crags still hold in the city skyline, one can only imagine the stir Douglass and his comrades could have caused had they been successful! The site is legally protected today as a scheduled monument.

Across the nation

Using 33 Gilmore Place as his base, Douglass’ campaigning involved much of Scotland, from major cities to small villages.

He appeared in large chambers and churches, in the City Halls of Perth and Glasgow, but also in more humble venues. One such venue was the Secession House in the Ayrshire village of Fenwick. Here, an “uplifting and rousing speech” was given to “an uncommonly large crowd”.

Houses in Fenwick village with Fenwick Parish Church in the distance, photographed between 1870 and 1880. (© Courtesy of HES Views of Fenwick Album).

A warm welcome wasn’t guaranteed everywhere, especially when Douglass was speaking against the Free Church. In Hawick in November 1846, Douglass was locked out of the Relief Chapel, at the request of Free Church deacons. There had been similar problems in Dundee the previous month. Douglass eventually spoke in the West End Chapel, “cheered with an enthusiasm such as has rarely been witnessed here.”

Despite this opposition, Douglass continued to spread the ‘Send Back The Money’ mantra. His rallying cry in Paisley Exchange Rooms was:

We want to have the whole country surrounded with an anti-slavery wall, with the words legibly inscribed thereon, SEND BACK THE MONEY, SEND BACK THE MONEY.”

“The good people of old Scotland”

Douglass made two anti-slavery tours (1846-1847 and 1859-1860) to “obtain the aid and cooperating of the good people of old Scotland”.

Along with denouncing the Free Church, he shared horrific insights into the institution of slavery. In Ayr, he named and shamed Thomas Auld and the damage he had done to Douglass’ family. In Paisley, he told the appalling story of a husband and wife separated when they were purchased by different slaveholders.

The Relief Church at 17 Cathcart Street, Ayr. Here, Douglass detailed his family’s ordeal at the hands of Thomas Auld (© Crown Copyright: HES List C Survey, 1975)

In a powerful speech given at John Street United Presbyterian Church in Glasgow on Valentine’s Day 1860, Douglass declared that he would rather suffer all the horrors of slavery again than live with the sin of being a slaveholder.

One thing is clear from all the newspaper reports and eyewitness accounts. Wherever he went, from Kelso to Kirkcaldy, Dalkeith to Duntocher, Douglass made a huge impact on the Scottish public.

The interior of John Street United Presbyterian Church

Despite calls for him to stay for good, Douglass opted to return to Massachusetts, to Anna, and to continue the fight against slavery on American soil.

Described as the most influential African American of the nineteenth century, Douglass’ role in turning public consciousness towards emancipation and equality was absolutely vital, no more so than in the country he called “dear old Scotland.”

For a detailed breakdown of Frederick Douglass’ activity in Scotland head to the National Library of Scotland’s dedicated site.

You can read about more remarkable figures, including Britain’s first Black teacher and the ‘Moorish lassies’ who served the Scottish royal court in our Black History archive.