When writing and researching Where Are the Women? A Guide to an Imagined Scotland, I spent six months remapping Scotland according to female history. All of the streets, statues, buildings and monuments I created were dedicated to real women, telling their often unknown stories.

A spotlight on the sidelined

During my research I worked my way through over 5,000 female biographies. My book tells the stories of more than 1,200 extraordinary women. But I couldn’t fit in everyone I wanted to – that’s how amazing our foremothers were.

For me, the purpose of this alternative world was to highlight the one-sided nature of how we memorialise history in our built environment and landscape. This therefore skews our perception of where we come from.

Not all the women were easy to find. I was committed to mirroring Scotland’s diversity in the memorials I invented and also honour women’s achievements. Not only ‘grand’ achievements such as scientific discoveries or leading trailblazing political movements, but also women who changed their local world. Perhaps a tea lady at a football club or a midwife in a remote community.

This reflects the way men are memorialised in real life – for their large achievements and small ones.

Sara’s research involved researching over 5,000 women in biographical dictionaries, obituaries, publications and more to find the stories of Scotland’s women.

Records of early modern racism

When it came to finding Black women in Scotland’s history, I searched long and hard. I was determined not to flinch from recording stories that emanated from our shameful past of slave ownership.

The earliest Black women I found lived in Scotland during the late medieval and early modern eras. Sir William Dunbar, a makar, wrote a poem intended to be comic in the late 1400s. He titled it ‘Of Ane Blak-Moir’, addressed to a Black woman providing entertainment at a tournament.

Poking fun at her physical appearance, Dunbar’s poem makes uncomfortable reading, to be frank, but it shows there were Black women in Scotland during the era. I raised an imaginary statue to this unnamed woman in my book.

Scotland’s Transatlantic Slave Trade

Not long after Dunbar’s poem was written, I found a record of ‘Blak’ Margaret and ‘Blak’ Elene. They were maidservants at Linlithgow Palace and Edinburgh Castle in the early 1500s. They had been captured from a Portuguese ship, which means they were trafficked.

In fact most of the Black women I found until I came to the modern era were connected to the Transatlantic Slave Trade in some manner, including freed slaves like Malvina Wells. She was from Grenada and came to Scotland as a servant to the family who had previously owned her. Today, you can find her buried in St John’s graveyard on Edinburgh’s Princes Street.

Malvina Wells’ grave is the only known grave in Edinburgh of someone born enslaved. Image courtesy of Rachael Lloyd and the National Records of Scotland, where you can discover more about Malvina.

Women of independent means

Other Black women came to Scotland because their white fathers endowed them with inheritances. Annetta Watson was the illegitimate daughter of slave owner Peter Watson. Born in Guyana, she inherited £6,000 when her father died (a substantial amount) and came to Scotland. First living in Innerleithen, she then become a music teacher in Glasgow as her inheritance dwindled.

Another black Scottish heiress, Margaret McGuffie, lived in Wigtown, where her father was Provost. Her house was called Barbados Villa and her story is told in a biography – The House that Sugar Built by Donna Brewster.

Agostino Brunias (Italian, ca. 1730-1796). Free Women of Color with Their Children and Servants in a Landscape, ca. 1770-1796. Oil on canvas, 20 x 26 1/8 in. (50.8 x 66.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mrs. Carll H. de Silver in memory of her husband, by exchange and gift of George S. Hellman, by exchange, 2010.59 (Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 2010.59_PS6.jpg)

The person who intrigued me most in this period is Dorothy ‘Doll’ Thomas – known as the ‘Queen of Demerara’ – who was a successful businesswoman. She arrived in Glasgow in August 1810 looking to educate some of her children and grandchildren in Scotland. Though a slave owner (registers of the period show her owning about 80 people), she appears to have stood up for her slaves including one called Sally, a pregnant black woman who was killed in police custody in Demerara (now Guyana).

Doll was a fascinating figure whose story runs counterintuitively to the common expectations of women of colour during the era. When she arrived in London it was said she had a skirt made out of five pound notes and a necklace of golden doubloons. She also leant money to her (white) son-in-laws when their businesses ran into trouble.

Woman and Child, a statue on Lothian Road in Edinburgh, was unveiled in 1986 to “honour all those killed or imprisoned for their stand against apartheid”. Image © Dianne King, part of the HES Archives.

Scotland’s links to South Africa

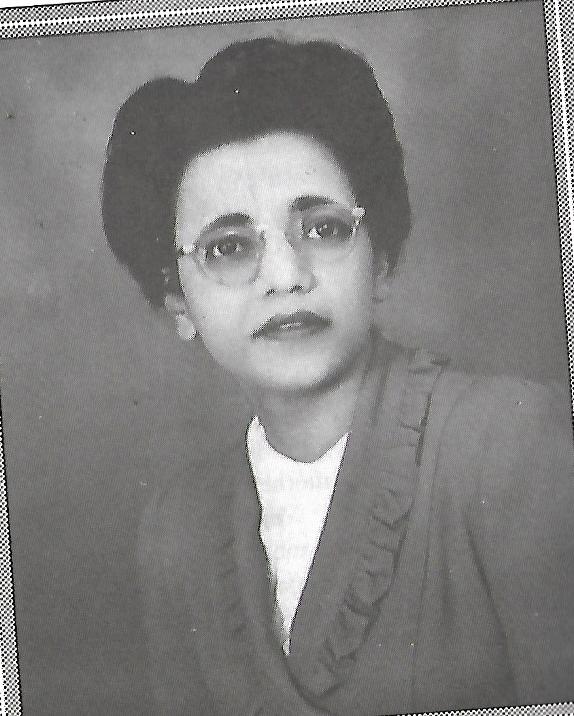

Later, I would come across women of colour who came to Scotland to study for degrees at our universities. One of them, Kesavaloo Naidoo, founded South Africa’s Resistance Campaign against apartheid in 1946. She served 17 jail terms for her fight against segregationist policies.

Educated at the University of Edinburgh, she returned to South Africa to vote in the first democratic election but in 1978 left to escape police harassment, only returning in 1990 after Nelson Mandela was freed.

Dr Kesaveloo Goonum, courtesy of Subry Govender

Unrecorded histories

The sources of these stories were varied.

Helpful academics kindly pointed me in the right direction and specialist blogs, including David Alston’s detailed and horrifying work on Scottish ownership of enslaved people, produced more stories. I also contacted community organisations and asked for tips – in one case being told that there simply wasn’t any material that they knew of!

Some records came to me by chance. I came across the Black maidservants at Linlithgow when I was scanning medieval material for another woman, and their stories have been well researched.

But what is telling is that, as far as I am aware, the stories of Scotland’s Black women are not gathered together anywhere.

We need to honour the lives of these women and there is a great deal more work to be done in understanding their stories and their contribution to Scottish culture and history.

A blank commemorative plaque – who would you commemorate?

Sara Sheridan is named as one of the Saltire Society’s most influential women, past and present. She’s known for the Mirabelle Bevan mysteries, a series of historical novels based on Georgian and Victorian explorers, and has written non-fiction on the early life of Queen Victoria. With a fascination for uncovering forgotten women in history, she is an active campaigner and feminist.