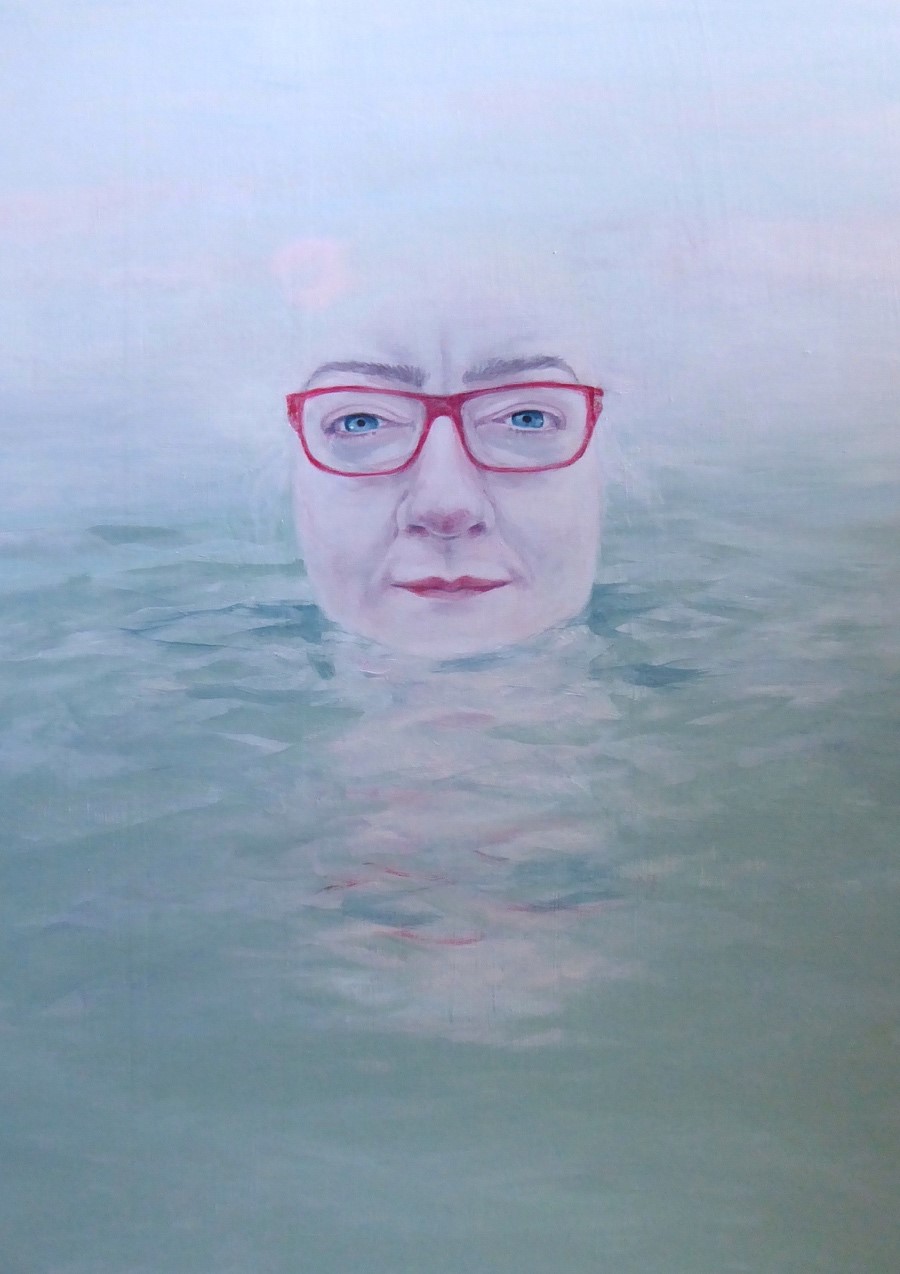

Do you find wellness in the water? In this guest blog, artist Morag Edward reflects on the crucial role swimming and the sea plays in her life, and documents the challenges and rewards of a sailing trip to the historic Highlands.

My mother taught me to swim when I was a baby and I soon moved on to enjoy swimming in the sea all year round. This included learning to read the water and the weather for safety, to know where to swim and when not to.

Swimming or just floating around in the water makes me very happy. Losing my health and mobility has only intensified that. The irony is that when I’m least mobile and in the worst pain and most claustrophobic is when I most desperately need to float in the open-air Scottish salt water.

The elephant in the room

Most Scottish beaches recommended for swimming are inaccessible to me. Even in the most famous beach of the capital city of the country there is no path across the sand. Scottish beaches with smooth paths right into the water are rare and invariably lead only to the edge of the sand or shingle shore, not into the water.

That elephant in the room is never mentioned in the increasingly popular sea swimming wellness write-ups and advice in the newspapers or medical articles or glossy coffee table books. Sea swimming is only good for your health if your health is good enough for you to get into the sea in the first place. It’s a cruel irony.

Floating fully supported and under the whole sky is transformative for mental, emotional and physical health and self-esteem. No claims are being made here for absolute cures. It’s about quality of life, inclusion and moments of bliss. And it’s free. If you are mobile.

Setting Sail

Without beach pathways or ramps to help overcome mobility difficulties, nowadays I need to approach the sea from a different angle. For me freedom of movement and access to the sea depends on a complex formula of a certain shape of boat, the right tide, suitable sailors and sufficiently good drugs.

Sailing in itself enables me to see parts of Scotland that would otherwise remain invisible. I can paint on my floating studio, with options of swimming, birdwatching, studying marine life or diving into coastal archaeology.

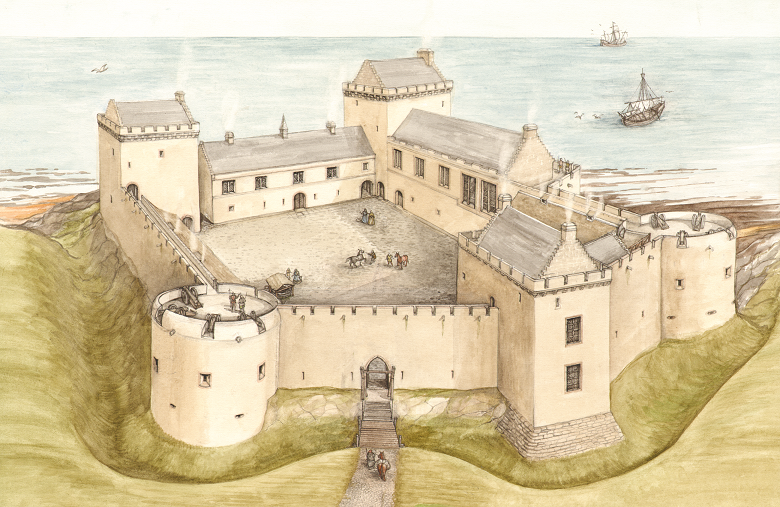

From the boat I get to witness Scotland’s rich array of coastal fortifications, lighthouses, islands, cliff colonies and castles as all outsiders would have seen them: by approaching from the sea.

Many of Scotland’s historic places relied on the coast or rivers for access and communications, such as St Andrews Castle, shown here in a HES reconstruction image

A coastal journey

Today I’m in luck. I have the opportunity to join friends for a coastal journey on a sleek transatlantic Rival 34 sailing yacht. She was restored through several icy winters of work, so they can easily sail her without any expectations of usefulness from my own painfully marshmallow-puffed hands. Once nimble enough to knot and strong enough to punch, they have deteriorated into this useless state through just two winters without medical treatment, so I’m now only a passenger.

This stretch of coastline we’ll be sailing is unknown so is another chance to search for swim spots. Gravity gets a swimmer into the sea from a boat, and on this expedition getting out again won’t be a problem because both of my sailors are so strong that either one of them could just lean over the gunwales to lift me straight out of the water.

We spend a serene evening moored at Seaport Marina, poring over pilot book, tide table and maritime charts to find a departure time in our favour.

On this lovely boat I have been generously allocated my own berth in the forepeak [a compartment in the bow of a small boat], with the elements I needed for independence: no way of falling over in there, and a comfortable mattress for when I just can’t move around.

On any days spent completely below, I will only have to open the forepeak hatch to see the sea and sky and wildlife and maybe other boats or cliffs and castles, which is all that I need to make just sitting up in bed a worthwhile life.

The yacht near Chanonry Point

Marvels and mudflats

Between us and the Beauly Firth is the Clachnaharry railway swing bridge and the oak and steel gates of the Clachnaharry sea lock, the 29th lock of the Caledonian Canal.

These sea gates are operated hydraulically by the official gate keepers, only during daylight hours, and only four hours either side of high water. I’ve never had a railway swing bridge opened for me before!

These mudflats of this Firth made for such challenging conditions that very inventive engineering solutions were required in order the make this end of the canal functional. The lock’s artificial embankments extend far out into the Firth to defeat the mudflats and release the boat into sufficiently deep water at high water.

The next time somebody tells me that building a pathway over a beach into the water would be too difficult and that maintaining it would be too expensive I will draw their attention to this sea lock.

All hands on deck

In the early morning, all hands are on deck, even mine. Choosing a seat requires some foresight. I must not sit where I’d potentially be required to leap swiftly out of the way, block a winch, risk getting a tiller in the backside or a boom in the face. And locks are not risk-free, not for crew or boat. Constantly adjusted lengths of mooring rope and a profusion of fenders are required.

Emerging through the final sea lock gate there is now extreme concentration focused on the depth gauge. This is not the highest of high tides. The estuary is wide and flat with strong tides and opportunities for crosswinds. The mainsail is raised.

Ahead is the earthquake-resistant Kessock Bridge, a steel cable stayed bridge with an evocatively named ‘harp system’ of rigging, opened in 1982. Out here all buoys are placed for traffic coming in towards Inverness from the North Sea, so exiting it is like driving in France with all markings on the wrong side of the road. Forget direction of buoyage at your peril.

Dolphins, and other distractions

There is a duty of watchfulness when on deck so I try not to be distracted by the sea birds or by my dolphin optimism, which is quite difficult. This area is new to me, and its an interesting time of year to be on the water.

The tourist season has passed, so there are no other yachts in sight, the puffins have left, the swallows are gathering along the coast to weave their migration plans, while the overseas starlings are arriving in great herds to murmurate with those already living here. The sun still feels warm on my skin but the air doesn’t smell of summer any more.

Past Kessock bridge we are now in the Moray Firth. In the distance, Chanonry Point sticks out from the Black Isle, which with Fort George sticking out from the other side creates the impression of a dead end across the horizon.

Chanonry Point is known for crowds of wildlife lovers keen to see the bottlenose dolphins, grey seals, harbour porpoise and minke whales that are regulars here. The dolphins are especially likely to hunt on a rising tide but will pose for photographs at any time if in the mood.

The lighthouse designed in 1846 by Alan Stevenson includes a range of lighthouse keepers’ dwellings all neatly painted to match. I think these buildings would make a wonderful site for a wildlife artists’ retreat. There are good campsites and big sandy beaches. I wonder if there are any solid paths anywhere on this peninsula that reach right down to the sea?

Thoughts on a Fort

The angular geometry of this stark garrison’s exterior seems more reminiscent of Venice and Morocco than Scotland.

The original Fort George was built in Inverness but was blown up by the Jacobites. Eleven miles East of Inverness on the flat land of Ardersier, its replacement is subtle, low and unobtrusive from a distance.

When close enough the wall is revealed to be dramatically angular, but it looks unsettlingly low and flat and passive for something intended for ferocious battle; a stealth fortress hiding a garrison of 2000 soldiers.

The stone was not quarried on site but painstakingly sailed over from a small quarry-harbour in Munlochy Bay across the Firth. It took a decade for around thirty dedicated boats to bring all the sandstone across to the building site. Family fortunes were made supplying and transporting the various materials required for this massive government project. It was built to last for centuries, and now operates as a Historic Scotland visitor attraction as well as a working garrison.

Fort George is one of the finest examples of artillery fortifications in Britain, though in the end it was never involved in a fight.

“A stairlift doesn’t fit inside a spiral staircase”

I am a big fan of Historic Scotland’s approach to their maintenance of the properties and their attitude towards visitors. Staff address me, not my wheelchair pusher. Only I am charged an entrance fee because my pusher is just part of my transport. I cannot describe the difference it makes to the experience to be seen as an actual person and acknowledged as the one in charge.

Normally I have very low expectations of access when visiting historic monuments, not least because I wouldn’t ever want to inflict any alterations that interfered with their preservation.

A stairlift doesn’t fit inside a spiral staircase, but I also know that with a little thoughtful engineering there can be raised walkways placed over cobbles or gravel paths that can through bends and twists achieve accessible viewing platforms up by the ramparts done in a way that does not draw attention to any ‘special favours’.

Rounding Fort George, several dolphins decide to appear. Next to us. Right next to us. We slow to enjoy the treat. The dolphins’ large audience wait patiently in the distance, but these Moray cetaceans want the shoal of fish currently around us. I try not to squeak with joy as they leap and jump and hunt.

Homeward bound

Eventually the dolphins gallop up the Firth to their waiting fans on Chanonry Point, and we head East along the Invernesshire coastline.

The sun is shining and there are some potential swimming access options near here for me to inspect and report back on. But not today. We need to round the headland to catch a good wind in our sails to take us home, and I need to lie down flat and still.

I think I know where to aim when next able to plan a Scottish coastal trip for investigations into accessible swimming possibilities around Historic Scotland properties. To completely misquote a certain song:

“I’ve sailed right down to Africa but I’ve never sailed to Aberdour.”

Morag Edward is a Scottish artist who is happiest in, on, under or next to the sea. Any sea will do.

We’d love to hear from you about how engaging with historic places has impacted your wellbeing. Check out our website for inspiration and information on how to get involved with our online exhibition.

This post was originally published on July 7, 2021 but we wanted to re-share as part of our ‘Historic Places, Breathing Spaces’ campaign.