This Women’s History Month, Historic Environment Scotland unveiled a new plaque to honour Mary Burton’s legacy.

Although she’s almost invisible in Scotland’s history today, there is much recorded about Mary Burton’s brazen campaigning. She is described as a social reformer. But she was so much more than that!

She was the first female Director of The Watt Institution, now known as Heriot-Watt University. She also fought for women’s suffrage. These facts alone, while they’re important to acknowledge, don’t help us paint a vivid, realistic portrait of Burton.

Humble beginnings

Burton was born on 7 August 1819 in Aberdeen to William Kininmund Burton and Elizabeth Paton.

Her father died, and so in 1832, she moved to Edinburgh with her widowed mother and her brother – the famous historiographer John Hill Burton (1809-1881).

Mary Burton didn’t receive any formal education and was home-schooled. By 1844, she had moved to Liberton Bank House in Edinburgh where a young Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) lodged at her premises.

The Sherlock Holmes author praised Burton as a steadying and supportive force in his life. © Dianne Sutherland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

From 1850 until the mid-1860s, there is a gap in the records of Burton’s history. However, we discovered that during this time she had signed up as a volunteer during the Crimean War (1853-1856). Burton’s obituary in the St. Andrew’s Citizen offers a glimpse of this period in her life. It states that:

Miss Burton was one of the company of heroic women who volunteered for service with Miss Florence Nightingale during the Crimean War, but an invalid parent and the care of orphaned relatives prevented her from leaving the country.

Burton was neither the first woman nor the last to put her family before her own desires, no matter how admirable they may be.

Philanthropist and rabble-rouser

From Burton’s documented will, we can gather that she owned several properties across Edinburgh. In the 19th century, many unscrupulous landlords presided over disease-ridden hovels. Burton proved to be an exception and we think that’s telling of her philanthropic character. Like an early version of a housing scheme, she maintained clean and affordable housing in Edinburgh’s Old Town. She rented them out to the city’s working poor.

By the mid-1860s, the press was avidly recording Burton’s reputation as a rabble-rouser. During this period, she became a Committee Member of the Edinburgh Ladies’ Emancipation Society (ELES), established in 1833. She joined the Edinburgh Ladies Educational Association (ELEA) established in 1867.

As well as fighting for women’s voting rights and their right to higher education, Burton was a member of the abolitionist movement which aimed to put an end to the Transatlantic Slave Trade System. This suggests that Burton cared about the plight of everyone, regardless of race or gender. Perhaps, if she was alive today, she would be at the forefront of intersectional feminism. Who knows?

The Marvellous Mary Burton will see you in court

In 1868, the year before the Edinburgh Seven made their entrance to the University of Edinburgh, Mary Burton was adding to the Midlothian patriarchy’s troubles.

The courtroom setting could have intimidated some, but not Mary Burton. She was here to claim her right to vote. She demanded to be added to the list of voters as a tenant of Liberton House, proudly and calmly presenting her case to the male sheriff presiding over the court. A representative of the Liberal Party, the advocate and two writers from the Conservative Party were also in attendance – and all men.

Burton opened the hearing by asking the sheriff, “what is the objection to me?”. During the hearing, she cited Acts of Parliament and 16th century laws. At one point, she even schooled the sheriff in the English definition of the word ‘man’! She essentially told him (we hope rather patronisingly) to look it up in the dictionary.

The fact that Mary Burton, a formidable, intelligent woman, wanted the right to vote was for many of the men present that day nothing short of ridiculous. The case was adjourned, and we can’t find any records of the outcome, but we think her bravery is nothing short of fabulous!

The fight for women’s education

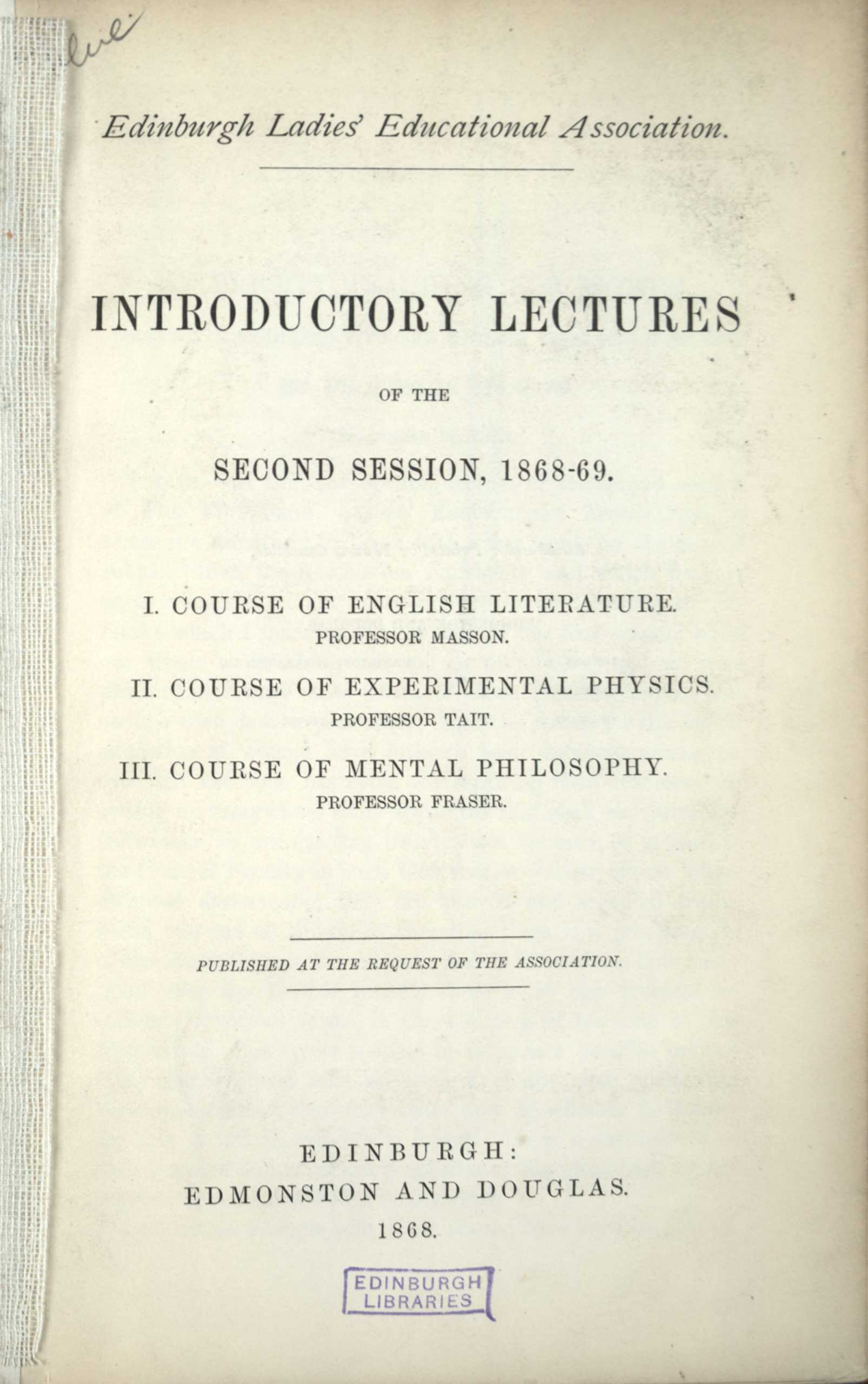

In 1868, the Edinburgh Evening Courant outlined the Edinburgh Ladies Educational Association’s (ELEA) aims and objectives in an article entitled ‘The Education of Women’:

Notwithstanding the numerous educational appliances existing in Edinburgh… young ladies who have completed the usual curriculum of private schools have no way of obtaining the higher education in science, philosophy, and literature which our universities offer to young men. This association has been organised to supply that want, and to furnish ladies after leaving school [in numerous subjects]… it is not the aim of the association to train for professions; but its promoters desire an education of women, to give them the advantages of a system acknowledged to be well suited for the mental training of the other sex.

Burton and the other members of the ELEA clearly saw education as a right and a way to empower the women who received it. It is evident that equality was a cause that ran deep in the Burton household. As a result, Burton’s two nieces also joined the ELEA!

The ELEA and Burton campaigned at The Watt Institution and School of Arts to admit female students. In 1874, Burton would become the first female director of the Watt Institution. She had more than earned this position through her years of campaigning!

Female students were finally permitted to attend lectures in English Literature, Logic and Mental Philosophy, Mathematics and Physics.

Adverts aimed at prospective female students that were placed in the newspapers indicated that up to 40 lectures could be had for £2.2s. This would be £250 today. © Edinburgh City Libraries (NC). Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Unequal access to education

We feel that it’s important to highlight the vast wealth disparity apparent in the social class hierarchy during this period.

Working-class women would not have attended these lectures. They had neither the disposable income nor the luxury of spare time. Middle-class women were in a position of privilege when it came to accessing higher education. Burton acknowledged this in her will: she bequeathed £100 to Heriot-Watt to be ‘given in prizes to the students of evening classes; to be allocated by the Principal of the college to deserving students irrespective of age or sex’. That’s equivalent to around £12,000 today!

Evening classes were frequented by working people and professionals aiming to upskill and thereby advance professionally. By giving this gift, Burton was actively supporting the endeavours of workers across the city.

Burton’s boldest battle: justice for sex workers

In 1871, Burton presented a petition to Parliament against the Contagious Diseases Act. This was a fairly bold move, even for Burton.

The Contagious Diseases Act was introduced to combat the spread of sexually transmitted infections. Police officers had the power to arrest any women they suspected of selling sex in specific ports and army towns, as well as certain areas within industrial cities. These supposed sex workers were then subjected to compulsory and invasive physical examinations for any signs of sexually transmitted infections.

If any signs of infection were found, the woman would be imprisoned in a hospital or workhouse infirmary until she was ‘clean’ again. These periods of imprisonment could last up to a year! The purpose of the act was to protect men from contracting sexually transmitted infections. The blame was solely placed on the female sex workers.

Other prominent women, including Florence Nightingale (1820-1910) and Elizabeth Garrett (1836-1917), protested against this outrageously sexist law. Eventually the acts were repealed in 1886 thanks to pressure from campaigners like Burton.

Mary Burton: Suffragist

In the 1880s, Burton became increasingly involved in the in the suffragist movement. She attended and participated in the Scottish National Demonstrations of Women. Thousands gathered at the event to protest, to hear speakers and to connect with each other.

Anna Munro was part of the Suffragette movement of the early 20th century. The work of Mary Burton and other women paved the way for future movements like this one. © Dianne Sutherland. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk

Mary Burton was elected to Edinburgh Parish Council in 1884, presumably because of her experience in providing housing for the city’s working poor. The parish council looked after all poorhouses and provided grant relief to those in need. By all accounts, Mary would have been a great addition to the council. The next year she became a member of the Edinburgh School Board.

In 1889, she signed a nationwide petition called ‘The Declaration in Favour of Women’s Suffrage’. The collected signatures were even published and presented to Parliament.

By the 1890s Mary’s health was failing, and she began to give up her various roles. On 8 October in 1897 she was admitted to Aberdeen Royal Lunatic Asylum at the age of 79.

We don’t know why Mary chose to move back to spend her remaining years in Aberdeen. But we can presume from her admission to asylum that she was unable to look after herself. In 1909 she died there but was buried in Dean Cemetery in Edinburgh.

This research is dedicated to a woman who achieved so much but still has little recognition in today’s society. We are so pleased that she has now received her own commemorative plaque.

The plaque to honour Mary Burton’s legacy was installed at Liberton Bank House in Edinburgh, where Burton lived between 1844 and 1898.

About the authors

The History Girls aka Dr Karen Mailley-Watt and Dr Rachael Purse specialise in researching women’s history in Scotland.

The History Girls aka Dr Karen Mailley-Watt and Dr Rachael Purse specialise in researching women’s history in Scotland.

They design and deliver heritage talks, workshops and publications and you can learn more about what they do on their website. Follow them on Twitter at @HistoryGirlsAye