When Edinburgh printer and businessman, James Donaldson, died in 1830, he left his estate to charity. His instructions were to build a facility to care for children who would otherwise have been living on the streets. Twenty years later, an impressive school building finally opened its doors at West Coates. Donaldson’s School, as it came to be known, became an important part of Edinburgh’s skyline and Scotland’s deaf history.

The building was designed by William Henry Playfair, one of the leading Scottish architects of the time. Playfair won a competition, which asked architects to design a building that was “Elizabethan” in style.

Initially, the school was known as Donaldson’s Hospital. Deaf children were not specifically mentioned in the original Trust Deed. However, during the long building project, school governors were so impressed by news of deaf education in other parts of Europe that they agreed to include deaf children on the roll.

An important milestone in Scotland’s Deaf history

To find out how many children needed this special education, parish ministers were asked to send details of deaf children and families in their area. This resulted in the first records of the deaf population size in Scotland. Thirty deaf children were accepted into Donaldson’s Hospital when its palatial building opened. This rose to 120 by 1880.

Queen Victoria officially opened the school in 1850, although it was not quite finished yet. Legend has it that she asked if she could exchange this building for the Palace of Holyroodhouse!

The 19th century approach

Deaf children were segregated from hearing children for their education and accommodation, but allowed to mix after school. This social time was well supervised to ensure no bad influences of language or other ideas!

The dual control model of leadership seems to have been successful in the smooth running of the school. There was general agreement in early years that the balanced mix of deaf and hearing students was an advantage to both. Deaf students gained valuable preparation for life in the hearing world; hearing students gained awareness of the difficulties faced by deaf people.

A portrait of Miss Elizabeth Orwin. She was the first matron of Donaldson’s Hospital between 1850-1868. Take a closer look at Miss Orwin on Canmore.

This unique system of integration stands in stark contrast to some modern approaches to deaf education. Interestingly, it was strongly supported, not only by Donaldson’s Governors, but also by the Corporation of Edinburgh City.

Changes in the 20th century

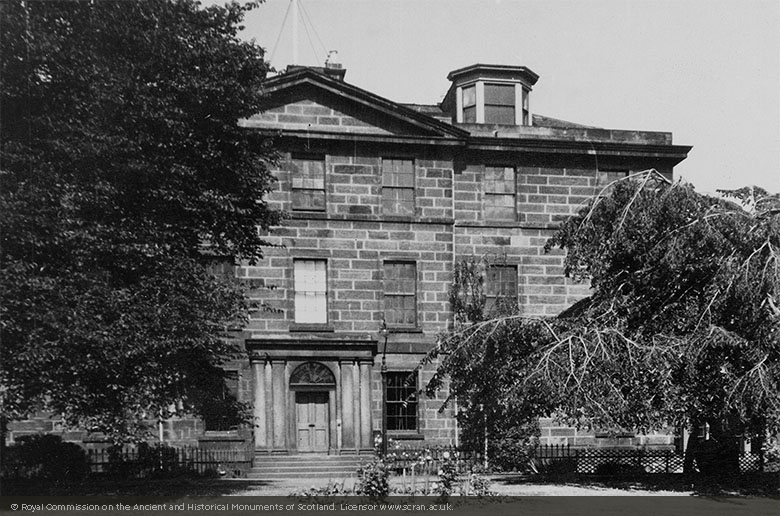

In 1938, Donladson’s Hospital amalgamated with the Royal Institution for the Deaf and Dumb which was based in Henderson Row. The school was organised into nursery, junior, senior and child guidance clinic with West Coates being its main base. Its nursery department fondly known as the “baby school”, was at Saxe-Coburg Place between 1916 and 1961. The Henderson Row premises, now known as the Donaldson Building, was used by Donaldson’s School until 1977. It is now ‘Category A’ listed.

The Donaldson Building at Henderson Row. Eagle-eyed readers might spot that this served as a filming location for the 1968 film of Muriel Spark’s ‘The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie’. Find out more about this building on Scran.

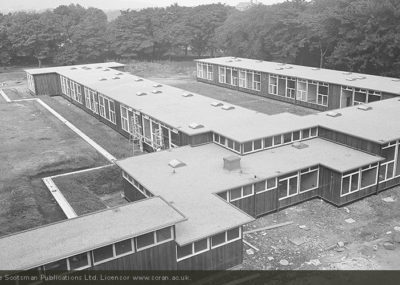

The Second World War interrupted significant development plans for the school. However, things eventually got underway in the late 1950s. Newly built facilities on campus included modern classrooms, an Art studio, a carpentry workshop, a domestic science block and a swimming pool. The old Playfair building was renovated to provide a library, a visual aids room, refurbished dormitories and bathrooms.

Life at Donaldson’s School

Boarding

Many of the children attending Donaldson’s were residential pupils. Some children were admitted to residential care as young as two years old. This was often done without preparation for the traumatic separation from their parents.

One former pupil, who started at age six, described her experience on that first evening. It was terribly upsetting when she discovered that mum wasn’t coming to collect her. Distraught, she cried and cried, wanting to go home to ‘my mummy and daddy, my brother, my sister, my dog’. It was a long time to wait until the next school holiday before the family could be re-united. Sadly, many children shared the same distressing experience.

Originally, ground floor rooms were used as classrooms and sleeping accommodation was on the first floor. However, as the school roll and buildings expanded, teaching was transferred to the new buildings. This left both ground and first floors for use by residential pupils.

Boys were accommodated to the left, girls to the right of the main building entrance.

There was also a “sick room”. Even when ill, many pupils did not travel home, and were instead cared for at school, in isolation if required.

Keeping time

For deaf pupils who live in a visuo-centric world, the clock tower was an important focus of the grand building. The headmaster’s office was located centrally in the clock tower on the ground floor. One former pupil recalls that the only time he saw a flag erected above the clock tower. It was on 24 January 1965: the day of Sir Winston Churchill’s death.

Take a closer look at the impressive clock tower on Canmore.

In the main entrance hall, a hand bell sat on a table. Every morning, boys congregated in this entrance hall. One former pupil recalled the daily excitement, wondering who would be chosen to ring the bell. The chosen pupil watched the hands of the clock approach the hour and rang the hand bell at exactly 9 o’clock. Profoundly deaf pupils were jostled into line by peers with limited hearing. Everyone stood to attention in straight lines, and filed into the assembly hall where every day began.

In the main entrance hall, large decorative shells adorned pedestals either side of the door. A hand bell would have sat on a table. You can take a closer look at those enormous shells on Canmore.

School rules

Former pupils recall a total ban on children in the quadrangle of the school. Some say they never even saw into it! Reasons for this were unknown to pupils. However, anyone who dared cross the boundary into the quadrangle was dealt with severely!

The quadrangle, which was out of bounds to pupils. Take a closer look and zoom in on Canmore.

Every school morning, dormitories and pupils were inspected with military precision, which filled many with dread. A mere missing button on a shirt could result in deduction of house team points!

Staff were accommodated in the nearby corner towers to enable close supervision, but of course, rules were frequently broken. For example, a group of girls reputedly stole food one night and sneaked it up to the boys. Pupils were interrogated by staff the next morning. They were keen to establish why there were supplies missing from the fridge and crumbs all over the kitchen floor!

Mealtimes involved duties for all residential pupils, like table setting. Again, some were prone to mischief! Boys serving soggy cereal to unsuspecting girls did not go down well at breakfast time!

The dining room as it appeared in 2002. Go to Canmore to zoom in.

Domestic and vocational skills

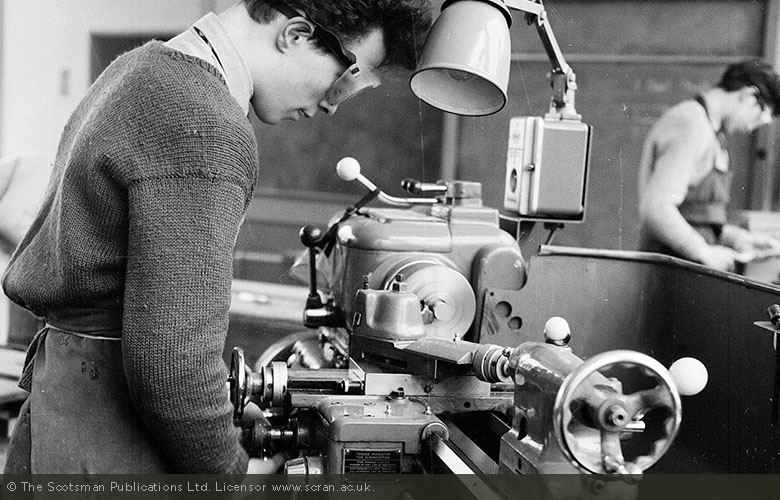

Although vocational skills were part of the curriculum in the 19th century, these seemed to disappear around the beginning of the 1900s. However, some vocational and domestic skills training was reinstated after the Second World War.

The new block built in the 1950s included sewing rooms and kitchens where senior girls learned domestic skills. It also included new carpentry workshops. Others included gardening, printing, tailoring and shoemaking.

Carpentry was one of many vocational skills offered to boys as preparation for future employment

Wartime memories

On 2 April 1916, German forces targeted many large buildings in Edinburgh. Just after midnight, a German Zeppelin flew over the school and dropped a bomb. It only narrowly missed the school building and created a huge crater behind the school. In the morning, the residential hearing pupils had to explain to their deaf peers why there was such chaos of upturned furniture everywhere!

All the windows of the chapel had been completely blown out, except for part of one ornate picture window. This remaining window section was preserved, removed and reset in a new location under the clock tower. The high quality stained glass in the chapel was replaced with more modest coloured glass.

This early photograph of interior of chapel shows the original stained glass. Head to Canmore to zoom in on the details.

During the Second World War, pupils were evacuated to North Berwick and Dunglass House in Cockburnspath, Berwickshire. Meanwhile, the building at West Coates was used for wounded German prisoners-of-war. Etchings drawn by soldiers were left on backs of shutters and the walls of the top floor. This visual piece of history was noted by pupils who attended the school after the war.

The end of an era

In the later part of the 20th century, many of the school’s annex buildings were sold off. By the 1980s, all ages of deaf children were educated on the original site at West Coates.

As Scottish educational policies of mainstream inclusion expanded, the numbers of pupils at Donaldson’s College, as it become known, reduced dramatically. In 2008, Donaldson’s moved to a new campus in Linlithgow. It continues there today, supporting pupils with a wide range of communication needs.

Meanwhile, the original West Coates building has been developed into luxury apartments. The building remains a ‘Category A’ listed building. Furthermore, it stands as testimony to the special architectural and historical interest which will always be associated with Donaldson’s School for the Deaf.

About the author

Ruth Donaldson is a third year British Sign Language (BSL) Interpreting student from Heriot Watt University. In early 2022, she worked on a pilot project to improve HES’s digital record for Donaldson’s School for the Deaf. This included collecting stories of social history from former pupils and recording these in both BSL and English format. She also spent time increasing the visibility of deaf and BSL records in our Scran and Canmore archives. This project was carried out in partnership with Heriot Watt University and Deaf History Scotland.

Feature image credit: Donaldson’s School photographed by George Washington Wilson between 1850-90 © Marius Alexander. Licensor www.scran.ac.uk.